By Yona Harvey

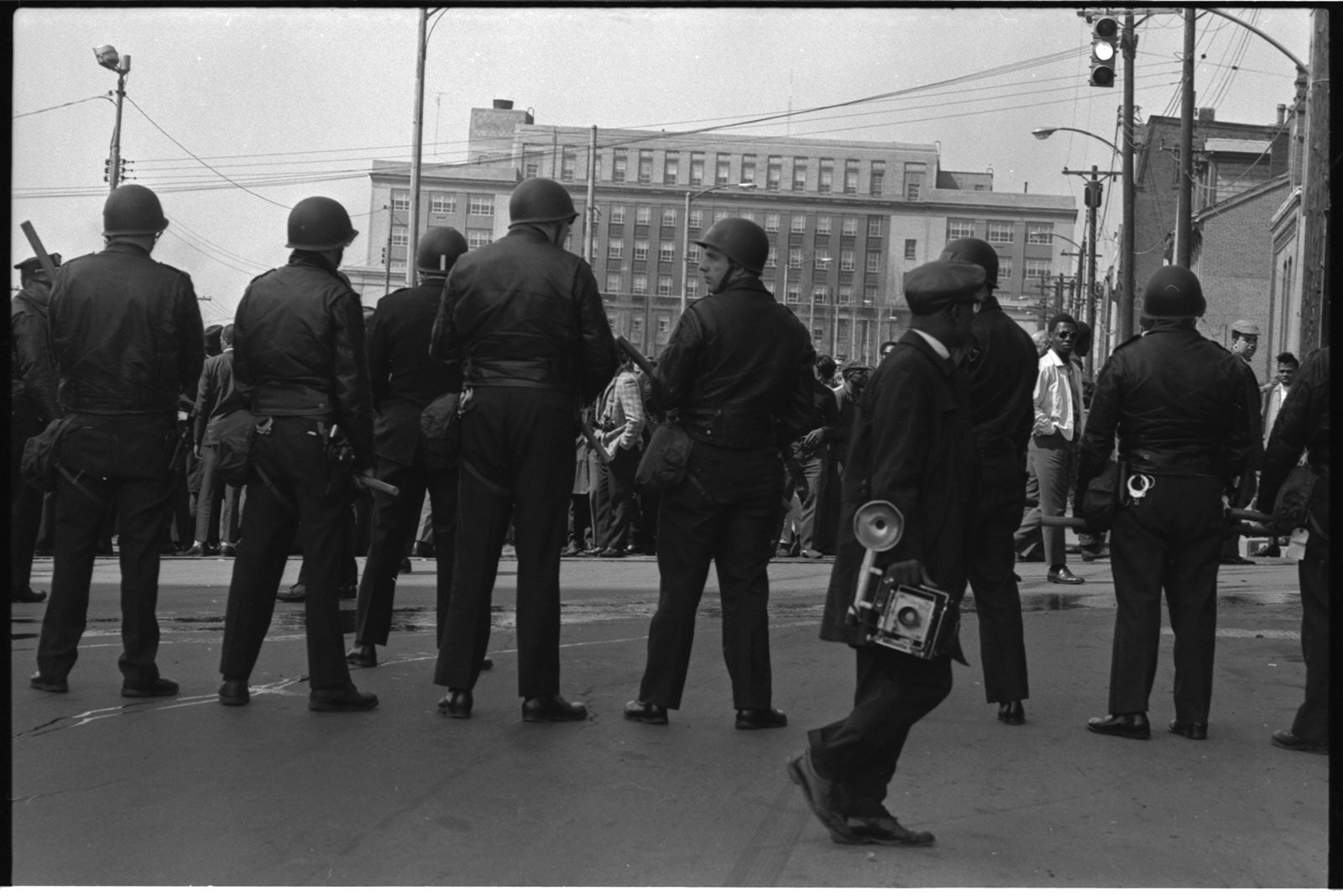

I’m standing alongside a life-sized photograph of police in riot gear. The image has obviously been enlarged, stretching body-length along the wall of an incline intimately holding 25 of Teenie Harris’s civil rights images. I’m jolted standing near the police like this—maybe what the curator intended? How not think of Ferguson, Missouri and Sanford, Florida? The inevitable moments of unrest that bind us? Whenever I view Harris’s photographs feelings of familiarity, uncertainty, and great curiosity surface.

I recognize beloved icons like Louis Armstrong, Mary Lou Williams, Martin Luther King, Jr., and many more who were hosted and supported by Pittsburgh’s black residents—laboring, posing, and protesting across time. Traversing the city, I look for their footprints at every moment. I am assembling the missing pieces of my adopted home.

* * *

Do you have family in the Teenie Harris photographs?I text my friend Joy, a Hill District native, mother, activist, poet, and artist.

When we meet later she says, “I don’t know. I haven’t seen his work. No time.” There’s a familiar contradiction in her answer. We live in a proud city that claims to be “livable”—but livable for who?

* * *

“I’m suspicious of a city that never had race riots,” I once said to Joy. We were crossing the street headed to our mothers’-night-out at Kelly’s Bar and Lounge with its retro sign holding its own among gentrified East Liberty eateries and hangouts.

“Pittsburgh had riots,” Joy said, correcting me patiently, but sounding slightly exasperated. Joy has organized or participated in every Pittsburgh movement I can recall (and dozens I can’t) including Occupy Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh for Trayvon, and What Happened to Teaira Whitehead? As a non-native Pittsburgher, I’m sensitive about putting my foot in my mouth and overlooking obvious facts, especially after living here over 13 years. I sometimes feel the disconnection between born-and-raised Pittsburghers—the descendants of all those striking faces in Teenie Harris’s photographs—and Pittsburgh transplants.

* * *

It’s 2008 and my friend Deesha and I have created a writing workshop for Winchester Thurston’s third grade Teenie Harris project. Each student will select a photograph and, using the prompts we provide, write a poem about it.

A few weeks ago, third graders were just beginning their annual “Pittsburgh, Our City” project. The list from which students could choose an “achiever” to research had been sent home and our presence was lacking.

“I’m emailing the teachers with names for the list,” Deesha tells me.

Among the missing were: Billy Strayhorn, Mary Lou Williams, Albert French, John Edgar Wideman, and Teenie Harris. What struck me was how easily the omission of names happened. It wasn’t even as if black names were stricken. Our names simply were not present. I was reminded of my initial doubts about the school.

Without Deesha’s persuasive pitch, I never would have enrolled my daughter. I often drove by in judgment, suspicious of the little school on the corner, whose name, as one woman once put it, sounded as if it should only be pronounced with a British accent.

“I don’t think that’s the right place for my kids,” I’d say, though I’d never actually visited. I’d never imagined a family like Deesha’s family there. We each have roots in the south, our eldest and youngest children are in the same grades, and our daughters plot sleepovers and “soul food nights” together.

The third grade teachers gladly add the additional names Deesha and I compile.

Not long after, the Teenie Harris project is born. As a creative writing instructor, I know firsthand how children benefit from the humanities and arts. But even I am surprised at the third grade students’ level of engagement: they take great care selecting striking images, like the photograph of a man who appears to weigh 300 pounds or the couples leaning in dark glasses from cars.

* * *

“How did he live, though? How did he die?” Joy asks about her fellow Hill District–raised artist. She has the camera’s eye, catching what everyone else misses—relentless, never letting anyone off the hook.

“This city has to take care of people before they die,” Joy has said many times. She knows in the 1980s Harris had to sue for royalties and the return of photographs that once filled the pages of the Pittsburgh Courier. The photographer won his lawsuit posthumously.

* * *

I’m drawn to what happens when the photograph is enlarged. The past is echoed within the present. The present echoes the past. As a city transplant, I drift from place to place, person to person, assembling a makeshift family, collaging some kind of narrative. Living well here means seeing the entire city, all of its people. No matter the school, no matter the neighborhood, no matter the shine of a new storefront window, to live is to see all the city’s people. It’s like being inside Harris’s camera, turning with the persistence of shutters clicking, pointing at this, now this, now this, now this, now this. That enlarged photograph of police in riot gear, taken by Forrest “Bud” Harris during the 1968 Pittsburgh riots, seems to perfectly capture Teenie in his environment—foregrounded on the street with his camera in hand. And on the wall it says that Harris was an artist on the ground.

I see Harris’s work in people like Joy and in Deesha—it enriches the images of Pittsburgh; it makes visible what others cannot see. Like Harris, Joy and Deesha have got this city covered. They’ve marked footsteps here. And here. And here.

Yona Harvey is the author of the poetry collection, Hemming the Water, winner of the Kate Tufts Discovery Award. Her work has appeared in many publications; most recently, The Volta Book of Poets. She is an Assistant Professor in the University of Pittsburgh Writing Program.

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.