Our son was born last summer via emergency Caesarean after 32 hours of labor. When his cries hit the cool, electric air, I sobbed uncontrollably, joining billions of parents across millennia who have loved their offspring instantly with a ferocity that makes the mouth speechless with awe and wonder. At 22 ½ inches, his legs were uncommonly spindly for a newborn, and he had two dimples, like my mother and my husband’s father. His skin was the color of toffee kissed by the sun. His hands were wide, and his fingers were so long, thin, and perfectly sculpted that friends and acquaintances on social media declared he would be a piano player. He is nearly one year old now, and the boy stuns us each day with his determination, sense of humor, laughter, and keen thoughtfulness and smarts. He is beautiful.

Less than three months after my baby was born, Lesley McSpadden lost hers—college-bound, unarmed teenager Mike Brown, murdered by a Ferguson police officer in cold blood. Her grief-stricken interview just hours after her son was killed haunts me to this day. It will never stop haunting me. I knew that Mike Brown was dead because he was black and male. I had just given birth to a black male son whose height is off the charts and will likely grow into “the big black man” white racists and police officers profile. He was napping one day when my husband and I discussed when we would have what is now known as “the talk” with our son: “If you are ever pulled over, son, do this, not this.” Though our son was a toothless newborn who existed on breast milk and could not use his two legs to walk from one room to another, my husband and I had to fill the room, our brains, our hearts, our intellects, and our love for him with a truth that makes me shiver: our son’s life is not protected in the United States because black lives are rendered as nothing—less than human and not nearly as precious as white people who occupy the nation. It was horrible to have a conversation with my husband about ensuring our son’s life when he had been alive only a few months. I felt as if the daisy of our moment had been trampled upon and months later, the man who was to blame—Darren Wilson, Mike Brown’s killer—walked away, galloping on a bed of daisies. What kind of land is this?

I wonder what images Teenie might have captured had he traveled to Ferguson during the protests. The fire in the eyes of a young man? The tears in the eyes of a child? A mother’s raised fist? Brown hands holding homemade signs declaring “Black Lives Matter,” calling out for freedom?

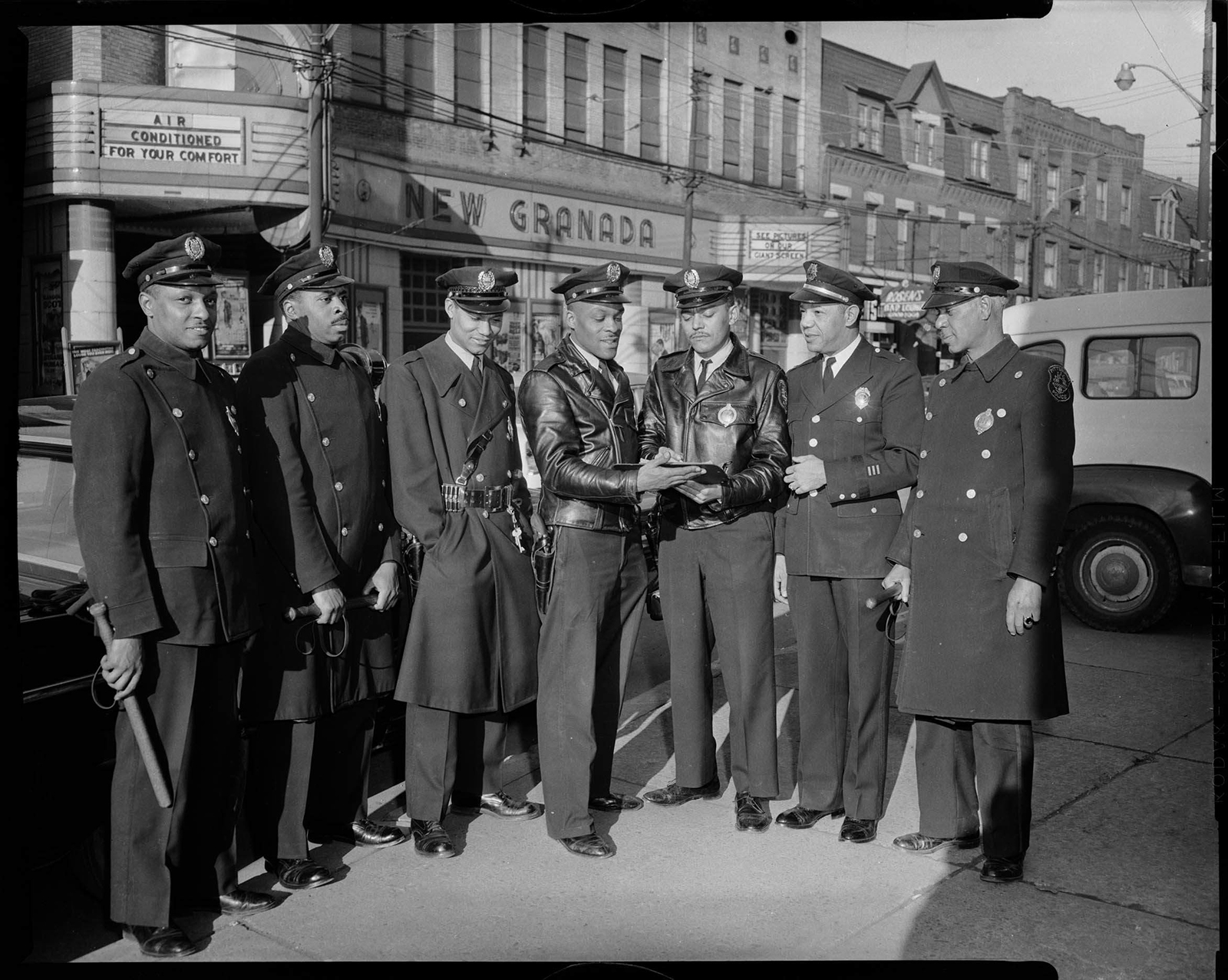

My gaze pauses for a moment on two of Teenie’s photographs that I love: Seven Police Officers, c. 1953–1960 and Members of the Black Panthers, c. 1970–1975. In each shot, I see power. The officers are elegant and resplendent in their uniforms; dutiful and dignified, their shoes spruced to a dull shine, their jaw lines immaculate; their faces full of honor, grace, and purpose; their job to serve and protect. The Black Panthers image reminds me what I loved about them: their sense of order, physical fitness, style, certainty, and love for the community; their job, like the officers, to serve and protect the black community from white racists, especially police officers who invaded black neighborhoods like warring locusts, ready to bust open heads, ready to take black lives.

These images capture a time long past. Today I am not sure how many young black men want to become police officers when they grow up, now that the devil-work of murder done by some has eclipsed the good intentions of others. Under the instruction and guidance of J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI successfully dismantled and destroyed the Black Panther Party, calling its community breakfast program for children “nefarious” and identifying the Party as the most immediate threat to US national security. Most of the members were either killed or imprisoned on trumped up charges. Yet in Teenie’s images, they live on and remind us of a time when to be a Panther or police officer was to live under the same banner: for the people.

I am thankful for Teenie Harris. I wish I had known the man. I wonder how he would have photographed our family. Would he have glimpsed the activist-artist in me, the wide shine of my son’s eye, my husband’s infinite kindness? Our hope, despite and because of this land? What would he have seen in us and what would his lens and talents have done with that love and magic? For when I look keenly at these two images of black men, all I see is love.

Tameka Cage Conley is a literary artist who writes poetry, fiction, plays, and essays. She is a Cave Canem Fellow and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize in poetry. She is the recipient of numerous fellowships, residencies, and awards, including the Eben Demarest Trust Grant in support of her novel-in-progress, This Far, By Grace.

The Teenie Harris Essay Series invites journalists, poets, playwrights, and historians to respond to the social, cultural, and political content of photographs from the Teenie Harris Archive.

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.