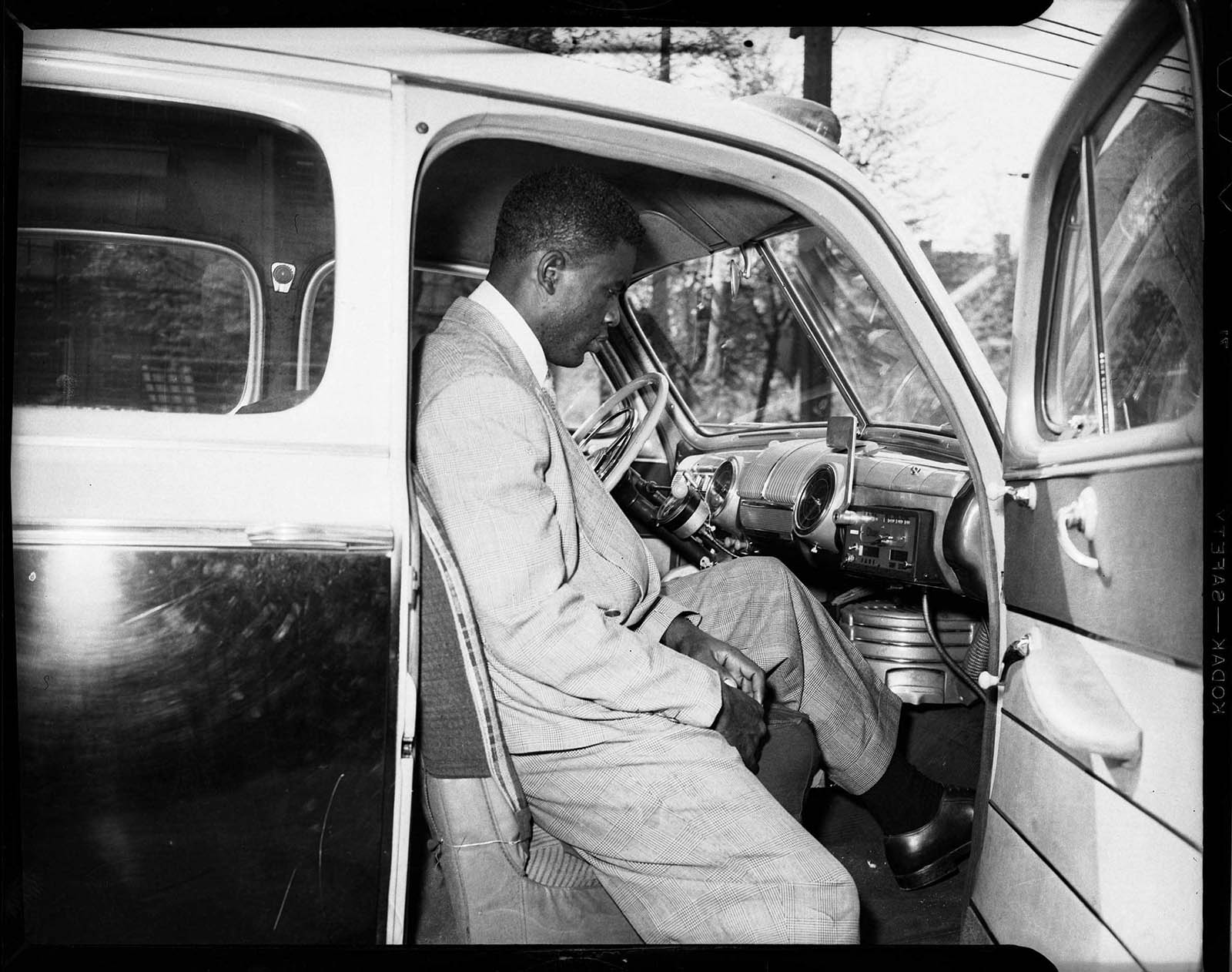

“Owl Cab Company was started by former jitney driver Silas Knox because Yellow Cab refused to come to the Hill,” says Kenneth Hawthorne, guest curator of the exhibition Teenie Harris Photographs: Cars.

The history of Pittsburgh’s historic Hill District and its ever-changing social climate are issues with which Hawthorne is intimately familiar. After all, he started his career by working as a mechanic at Hawthorne’s Esso, his father’s service station on Wylie Avenue in the Hill, before eventually going on to become a vice president at Gulf Oil. Owl Cab Company, as well as their competitors and local jitney drivers, all had their cars serviced at Hawthorne’s.

While Yellow Cab’s refusal to provide service to residents of the Hill was just one example of the many ways African Americans were discriminated against during an era of segregation, it also revealed a longstanding problem: the transit gap in black communities. Before Knox established Owl Cab Company in the 1950s, jitneys were a mainstay on Hill District streets. The creation of a black-owned cab company, however, was a major development—not to mention an investment risk for Knox.

According to Mr. Hawthorne, Owl Cab “had a miraculous financial start, because loans of its size were not available in the Hill District.” He also notes that Pittsburgh Police encouraged Owl as an alternative to “help stop the jitneys,” which were illegal and not licensed through the city.

While historical discussion of segregation often centers on its overt moral indignities, being treated as second-class citizens also posed African Americans with a host of other practical challenges in everyday life—from difficulties in obtaining mortgages and health insurance, to an inability to purchase car insurance. And as Mr. Hawthorne states, substantial business loans from banks were not an option for most black businesses.

Jitneys have a long history in Pittsburgh, with generations of Hill residents relying on their services when white-owned cabs refused to send cars to black neighborhoods. So while jitneys were and remain illegal, the need for them has been a reality dating back to 1914. In fact, jitneys or “Gypsy Cabs” are so pertinent to African American culture, that Pulitzer and Tony award winning playwright, August Wilson (himself a native son of the Hill), won best play at London’s 2002 prestigious Olivier Awards (London’s version of the Tony) for his play Jitney, which centers on life lessons learned at a jitney stand.

Silas Malik, son of Owl Cab Company owner Silas Knox, says his dad had once been a jitney driver, and as Knox himself stated, “Jitneys were created out of a need for service,” and that became a very serious concern for him. Knox had just served two years in the US Army, and had moved to Pittsburgh from St. Louis in hopes of starting a black-owned cab company. Malik says that after being insulted in 1938 by a white Yellow Cab driver who refused to take him to the Hill District from the Pennsylvania Train Station, his dad gave the white cabbie his fare and remarked “the tip I gave him was that I had spent two years to risk my life for bums like him.” At the Pittsburgh Courier office on Centre Avenue, Knox was told “Yellow Cab doesn’t hire any colored drivers.” The two incidents further settled his decision to open the Owl Cab Company.

Malik’s earliest memory of being at the Owl office was as a six-year-old boy, when he was given the job to sweep and clean up the cab office after school. At eight years old, his dad put him in charge of the log sheets as the cabs came in for the day, and taught him how to work an old-fashioned adding machine. At age 11, his dad taught him to drive and he would watch the cabbies jack up a car to fix a tire or work on the engine, which resulted in his learning a lot about car repair. Others who frequented the cab and jitney stands in the Hill District have often recalled learning about more than just cars—they learned about life.

Plagued by financial difficulties, the Owl Cab Company eventually went out of business, with subsequent imitators following their template of fine service. To this day, if you mention Owl Cab to many Pittsburgh natives, their faces beam with happy recollections of bygone days riding in clean, reliable cars with courteous drivers. And even though Yellow Cab and other companies came to hire black drivers, jitneys still service the Hill District and other African American neighborhoods in Pittsburgh and cities across the country.

Charlene Foggie Barnett is the archive specialist for the Teenie Harris Archive at Carnegie Museum of Art. Working with the collection’s approximate 80,000 images, she helps identify photographs, interacts nationally with the African American community to collect ID’s, and records oral histories that result from the exhibitions, outreach events, lectures, blogs, and tours that she organizes. Not only does Foggie Barnett work for the Teenie Harris Archive, she personally knew Charle “Teenie” Harris and was photographed by him from the time she was three months old until her mid-twenties. Among other accolades, she was recently named one of 50 Women of Excellence by the Pittsburgh Courier.

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.