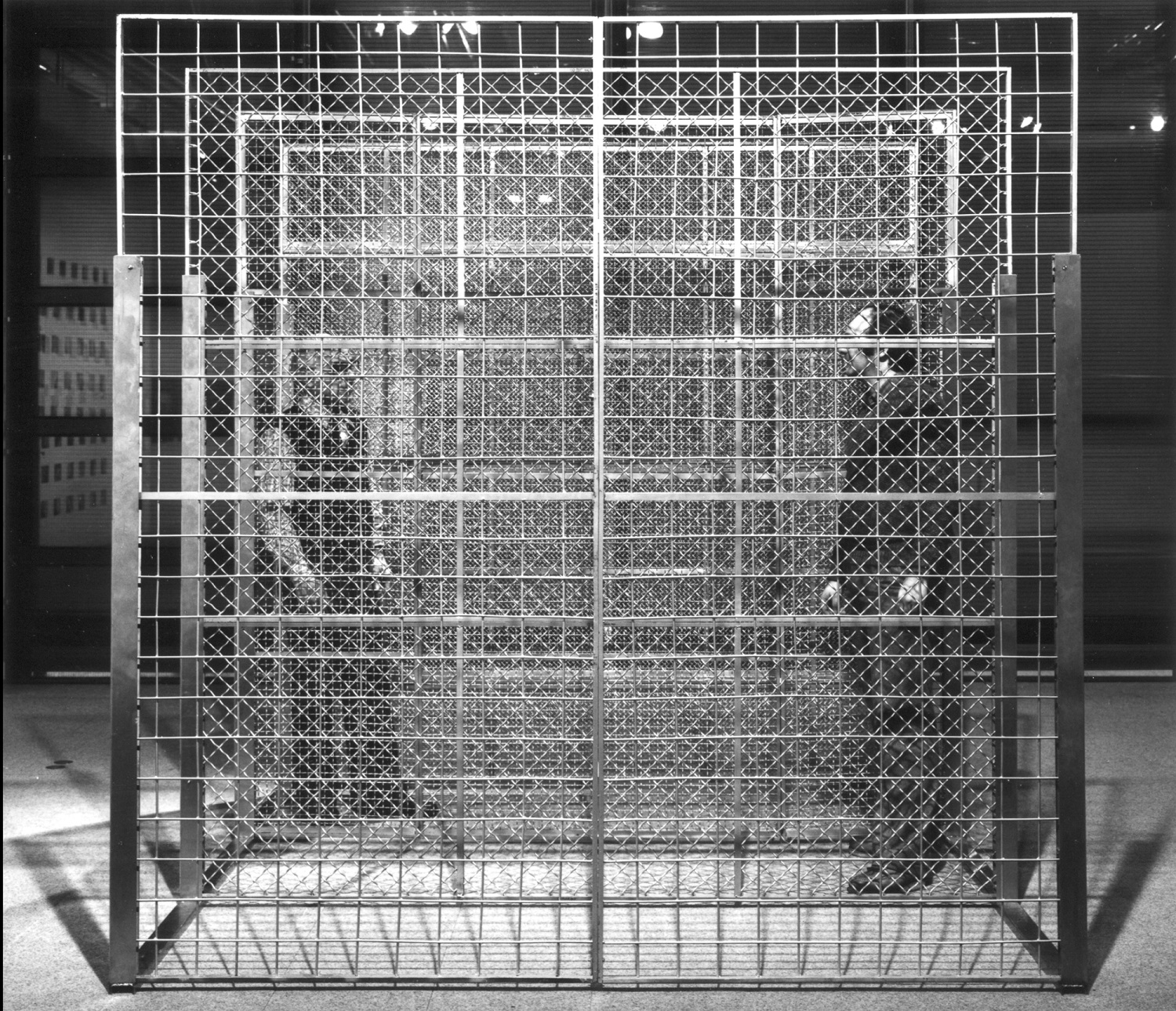

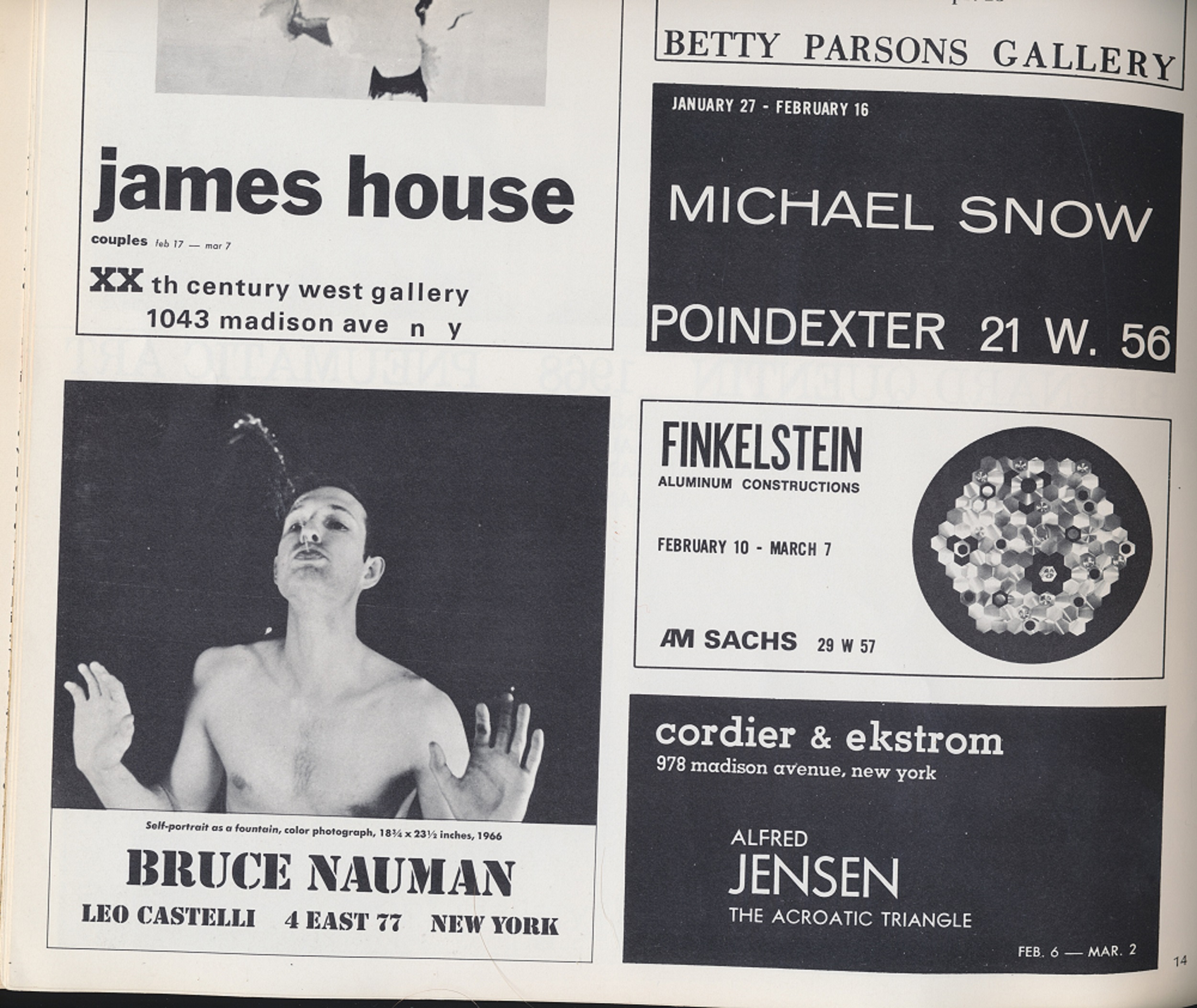

Hollis Frampton’s film Snowblind (1968) binds things together. The title, like the compound word on which it is based, fuses an effect (to be blinded) back onto its cause (by snow). Unlike the term whiteout, which describes conditions that can result during a blizzard, snow blindness refers to the aftermath, indicating an extreme (most would say compromised) state of vision brought on by exposure to the reflective brilliance of sun-drenched, snow-covered ground. But Frampton (1936–1984) puts a positive spin on this affliction by using his title to herald the subject of his film: Canadian artist Michael Snow’s sculpture Blind (1967), first exhibited at New York’s Poindexter Gallery in 1968. The contraction of artist and artwork to a single word (“Snow’s Blind”) is simultaneously expansive. It folds in sensation.

During the same month that saw the debut of Blind, Snow (b. 1929) unveiled his Snow Storm, February 7, 1967 (1967) in Paris.1 Frampton’s explicit tying of precipitation to Blind echoes the title Snow Storm, providing an important extension from one Snow piece to another, and from the Poindexter (where Frampton’s film was shot) to the Musée National d’Art Moderne (where Snow Storm was exhibited).2 That latter work emblematizes Snow’s activity in multiple mediums: it hangs on the wall like a painting, contains the sculptural element of relief, includes still photographs, and hints at animation via the depicted snowfall and the changing pattern of cut-outs on each quadrant. With the then-recent success of Wavelength (1966–1967), Snow’s pursuits also encompassed live-action filmmaking.3 Snowblind celebrates Frampton’s good friend’s early 1968 flurry. The film is a record of Frampton being snow-blinded by Snow’s storm of energy.

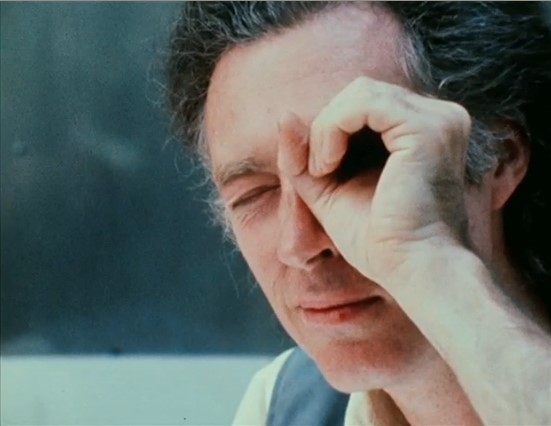

Blind was recently described by the artist himself for a group of people who could not see it. The occasion was not as spectacular as might be imagined. Snow was not detailing a lost object (Blind sits safely in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Canada, in Ottawa); nor was he involved in a special session of the American Council of the Blind’s Audio Description Project (despite the fact that individuals’ loss/absence of sight has likely always been on Snow’s mind given his father’s onset of blindness from the time Snow was five).4 Instead, Snow was responding to the request of a podcast interviewer. When the host of the show Modern Art Notes asked his guest to aid their ear-only audience in picturing Blind, Snow gave this spur-of-the-moment sketch of the nearly fifty-year-old piece:

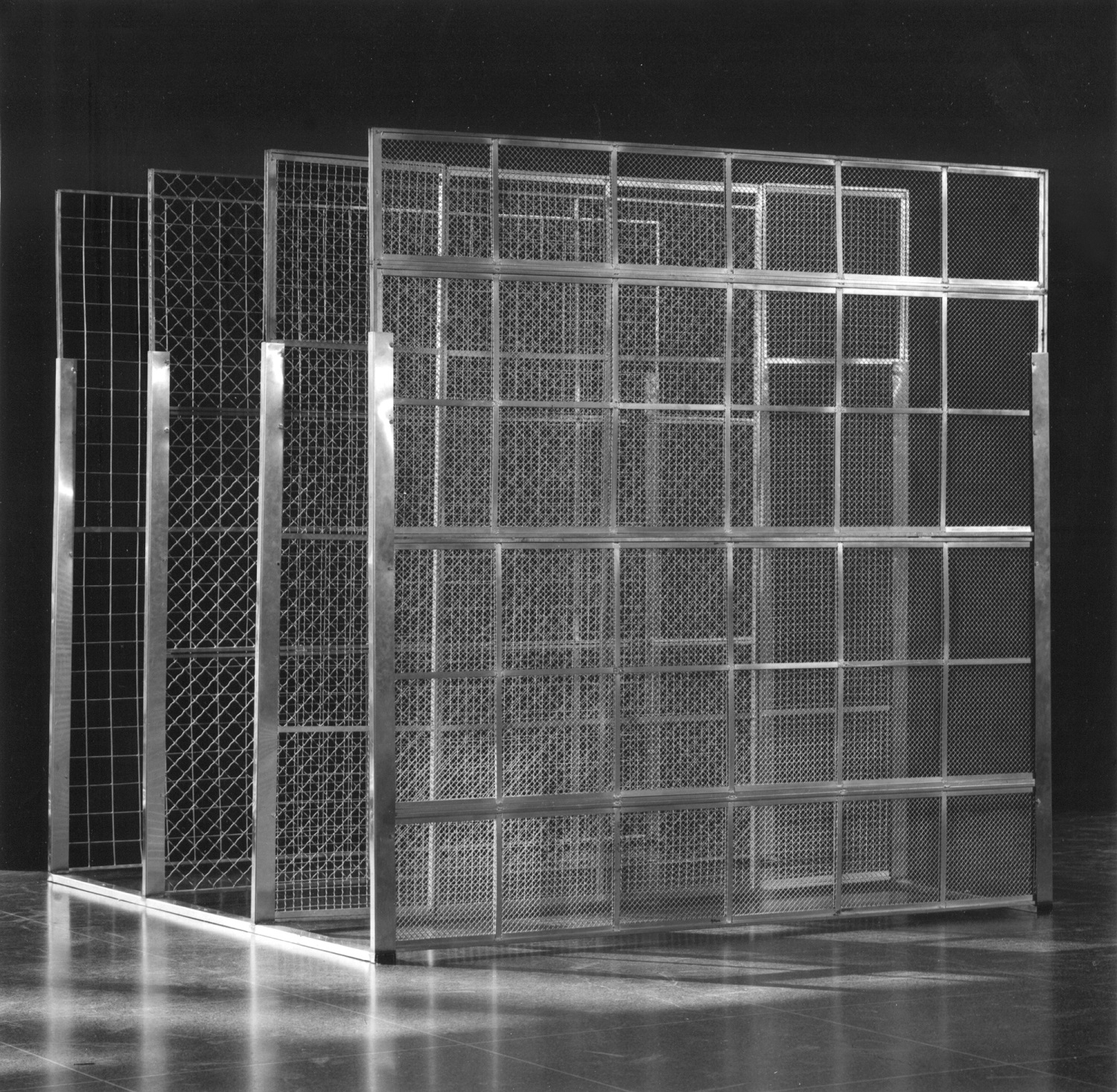

Blind is a piece of sculpture, which has four panels (I guess you could call them) of screening (I guess you could call it) separated by a meter, or something like that. The four of them are standing upright. One can walk in between them, but the four panels are different: each is a different density of wire, and one of them—the wire is going diagonally—and then the next one—the wire is going vertically and horizontally—and they go from small to big. So what you have is something to look through, and every particular, every position that you have, it’s like a great big cross-hatch drawing, where every move that you make to move through it makes a different layering of the metal lines, and then, when you focus on the lines themselves, or when you are looking through them, it really has an almost infinite number of viewing situations.5

Snowblind has just been preserved as part of Anthology Film Archives’ ongoing Hollis Frampton initiative. Carnegie Museum of Art’s print of this 16mm film wound up being used as the master element because Frampton’s original materials were in less than ideal shape, probably due to lab mishandling in the late 1960s.6 Around that time, Frampton had written this program note for the Film-Makers’ Cooperative Catalogue (1971), published by New York’s main distribution center for avant-garde film:

A souvenir of Michael Snow’s environmental sculpture BLIND. The film proposes analogies for three perceptual modes enforced by that work.7

A few years later, Frampton changed his copy for a new 1975 edition of the catalogue:

Hommage [sic] to Michael Snow’s environmental sculpture BLIND. The film proposes analogies, in imitation of 3 historic montage styles, for three perceptual modes mimed by that work.8

As evidenced by the play with Snowblind’s title, Frampton’s attention to specific words, including, in this case, French spellings, needs to be taken seriously. The small changes of “souvenir” to “hommage” and “enforced” to “mimed” matter. “Modes mimed” increases the m‘s as in “hommage” and emphasizes the idea of the unspoken in this silent film (since mimes are mute).

Frampton once complained of Snowblind falling on deaf ears. During a 1978 interview with Scott MacDonald, when talk turned to “the most circulated of [Frampton’s] films,” Frampton grumbled:

There are films that I could just as well take out of the Coop. Heterodyne [1967] and Snowblind are never rented. Palindrome [1969] rents three times a year in a nation of 240,000,000.9

According to the rental records (still) kept at the Coop, Frampton’s use of the word “never” was an overstatement. It would have been better to say that Snowblind was rarely rented; but better yet, the film had just been bought.

To augment the three Frampton films already in its holdings, Carnegie Museum of Art purchased Snowblind and five other Frampton titles in 1977. Lemon (1969) and Zorns Lemma (1970) had entered the museum’s collection in 1972, and Apparatus Sum (1972) had done so in 1976. The addition of these six works highlights Frampton’s importance in 1970s visionary film generally and Carnegie Museum of Art’s film programming specifically: Frampton had screened there as one of the museum’s earliest in-person guests in January of 1971, and again in 1974 (as well as in 1978). It also calls attention to the role that the city of Pittsburgh played in Frampton’s filmmaking. Carnegie Museum of Art’s founding “Coordinator of Films,” Sally Dixon, whose correspondence with Frampton reveals the warmest of friendships, secured the filmmaker access to Homestead Works through the United States Steel Corporation in early 1971, and to the University of Pittsburgh’s anatomy lab and Buchla synthesizer later that same year (when Frampton came back to town for a gig at Chatham College [now University] that was also coordinated by Dixon).

That two of the three Frampton films that make use of Pittsburgh material—Apparatus Sum (anatomy) and Winter Solstice (1974; steel)—joined Frampton classics like Lemon and Zorns Lemma makes sense, though one wonders about the missing Special Effects (1972; synthesizer). The motivation for adding Frampton’s beloved Critical Mass (1971) and (nostalgia) (1971), which had its surprise world premiere at Carnegie Museum of Art, is also clear. But the remaining titles that filled out the 1977 accession—Manual of Arms (1966), Snowblind, and Less (1973)—were less obvious choices. While they do form a cohesive grouping in their close connection to artists (a sensible roundup for a museum of art), they had to be separated out from related films in Frampton’s oeuvre: Artificial Light (1969), Yellow Springs (1972), For Georgia O’Keefe [sic] (1976), and Quaternion (1976) (though perhaps the last two were a little too late for that round of acquisitions).10

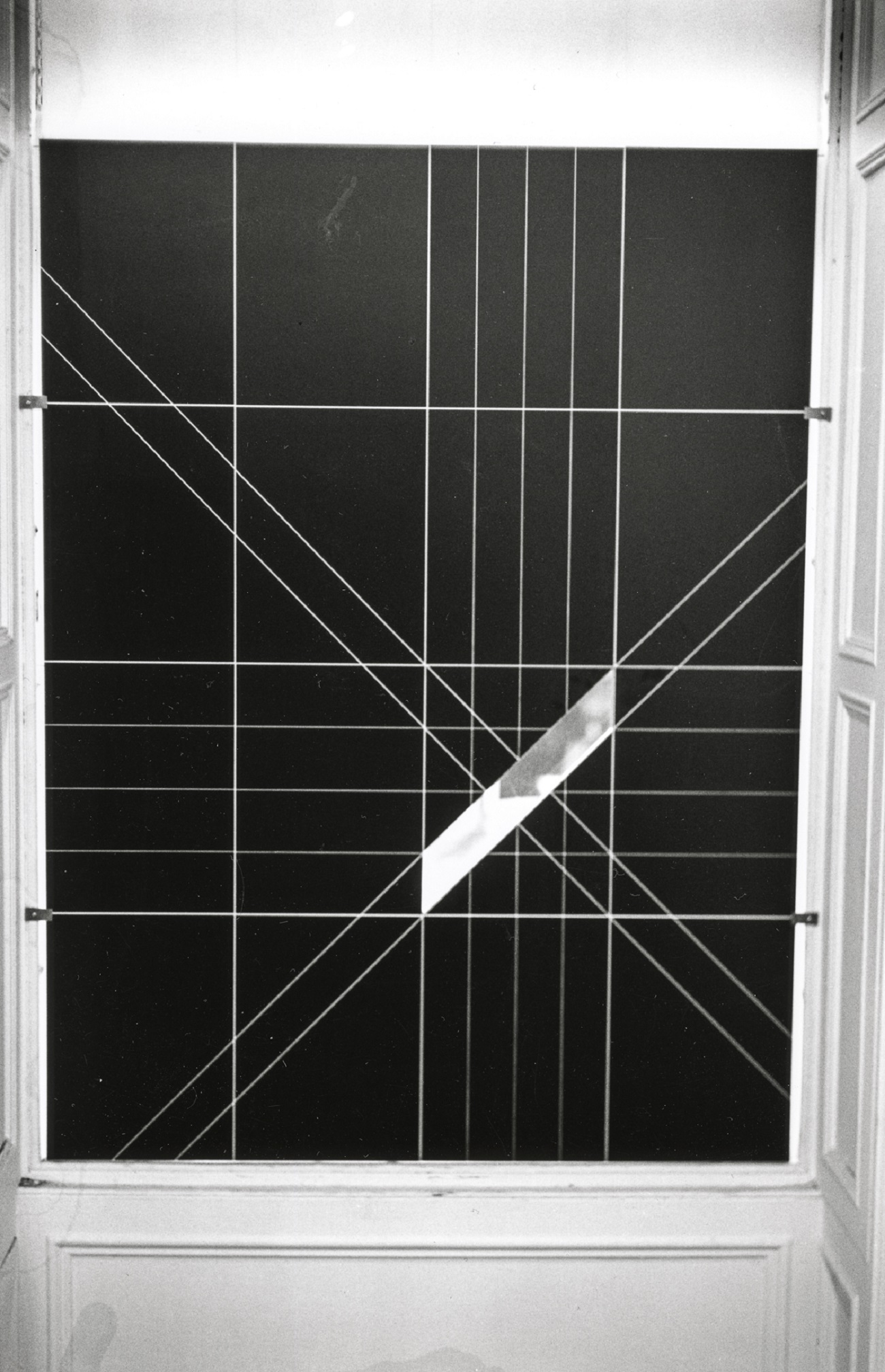

Carnegie Museum of Art’s involvement with the restoration of Snowblind forty years after its addition to the collection seems, somehow, to have been foreseen by the host of our aforementioned podcast. Back in 2014, when Tyler Green was interviewing Snow about his second major US museum exhibition of photographic work, the critic kept returning to questions about related sculptures from the 1960s. Green was teasing out Snow’s increased use of still photography by that decade’s end (the impetus for Green’s Snow episode was the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Michael Snow: Photo-Centric; the first such US exhibition had been the Museum of Modern Art’s 1976 Projects: Michael Snow, Photographs). Keeping in mind Snow’s start as a painter in the 1950s, Green forged a link between the diagonal strip of light in Snow’s sculpture Sight (1967) and the one in John Singer Sargent’s Venetian Interior (ca. 1880–1882).11 Although Green does not position Snow’s Venetian Blind (1970) as an intermediary, and may not have cared that Sight was originally shown with Blind at the Poindexter, the fact that the Sargent painting has been part of Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection since 1920 begs questions of predestiny. That Carnegie Museum of Art’s 1972 poster for Snow’s visit to Dixon’s “Film Section” looks to have been inspired by Sight adds to the feeling that Carnegie Museum of Art’s role in prolonging the life of Snowblind was meant to be.

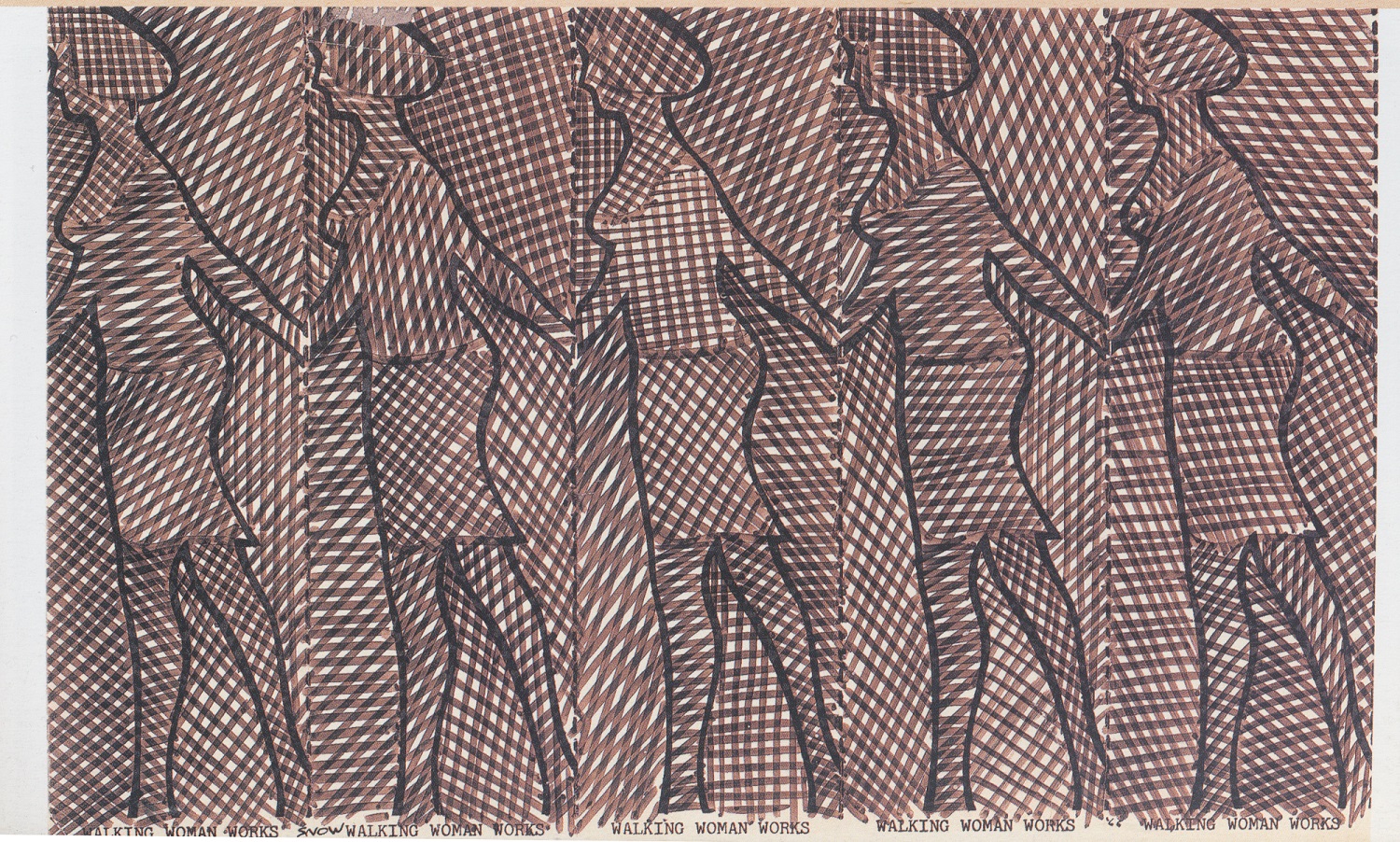

The two other sculptures exhibited at Poindexter Gallery in 1968 were Scope and First to Last (both 1967). Together with Blind and Sight, they produced an incredible “ensemble” of thinness and bulk, of solidity and porousness, of apertures and vistas. As Philip Monk has described the group, all four “are as much to be looked through as to be looked at.”12 The show was Snow’s third one-person affair at the Poindexter. The two earlier instances, in 1964 and 1965, were both made up entirely of Walking Woman Works (WWW), the wild series that Snow began in 1961 (the year before he and Joyce Wieland relocated from Toronto to Manhattan). This series lasted until a grand finale of sculptures at the Ontario Pavilion for Montreal’s Expo 67. Two of the approximately one thousand WWW stand out as precise precursors to the four Poindexter sculptures.13 Even though Cry-Beam (1965), Seen (1965), and certain selections of ephemera and documentation collated in Snow’s artist book Biographie of the Walking Woman/de la femme qui marche, 1961–1967 (2004) also seem germane, it is the pair Morningside Heights and Sleeve (also both 1965) that contain components that separate off in order to be “looked through” (recall Monk, and also Snow, above).

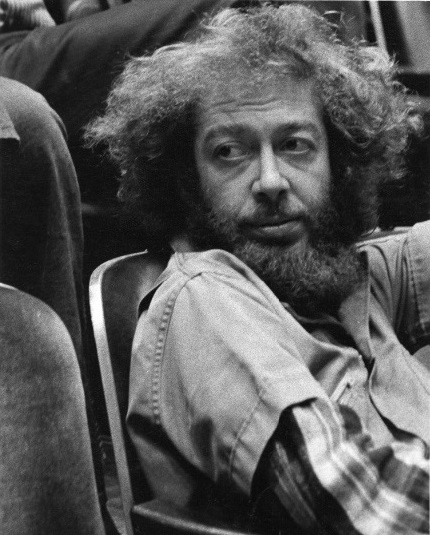

It was Sleeve that appears to have marked the official beginning of the collaborative relationship between Snow and Frampton. Moving to New York in 1958 as a poet, Frampton quickly turned to photography (high-school friends Carl Andre and Frank Stella, as well as their sculptures and paintings, were early subjects), before committing himself to motion pictures by 1966. Snowblind, made two years into his shift to cinema, was Frampton’s sixth film. As Snow recalled in a wonderful tribute to Frampton, the two kept seeing each other in 1964–1965 at gallery openings and at experimental film screenings held by the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque.14 The conjunction is important, as Snow felt that there was not much crossover between the regulars at these venues. “Sometime in 1965”—to cite the autobiographical voice-over written by Frampton, but famously recited by Snow, for (nostalgia)—Frampton had photographed Snow at his studio during the lead-up to Snow’s second Poindexter show. This image, shot through the window portion of Sleeve, was used for the gallery’s poster and discussed on (nostalgia)’s soundtrack by Snow himself:

As many as possible of the pieces are seen, by reflection or transmission, in a transparent sheet of acrylic plastic which is itself part of a piece. The result is probably confusing, but no more so than the show apparently was, since it seems to have been studiously ignored.

If you look closely, you can see Michael Snow himself, on the left, by transmission, and my camera, on the right, by reflection.15

Between 1965 and 1971, the two also played other roles in each other’s art. Snow is in Frampton’s Manual of Arms as Frampton is in Snow’s Wavelength. Another Frampton photo shoot produced one of the portraits used in Michael Snow/A Survey (1970). Frampton’s performance piece “A Lecture” (1968) used Snow’s voice to read a manifesto of Frampton’s, and the two hatched a theatrical interview of Frampton (late 1968/early 1969), which was published in Film Culture in 1970.16 Of course, during these rich years before both men left New York City, there was also Snowblind.17

The closest consideration Snowblind has received is that by pioneering Frampton scholar Bruce Jenkins. In his 1984 dissertation on Frampton, he builds upon both Coop catalogue statements and the filmmaker’s response to MacDonald’s question about the film:

MacDonald: In the Film-Makers’ Coop catalogue you mention that Snowblind proposes analogies for three perceptual modes and three historic montage styles. I think I understand the three perceptual modes—if they are perception while in motion, while light is changing, or while refocusing—but what montage styles are you referring to?

Frampton: The problem was to reconstruct an object which subsists in deep space and is ambiguous: specifically, a sculpture called “Blind” that Mike Snow showed at the Poindexter Gallery in 1967 [sic]. In classic film editing, there are at least three strategies for reconstructing a deep-space object: one is to look at it and go around it; another is to pass through it; and another is to retrieve the object by retrieving an interaction of something else with it. The third is the most obvious. The last section of the film, where Mike gradually walks out of the piece in that “cubistified” way, is an obvious parody of the typical Eisensteinian gesture of intercutting the same action three or four times from three or four different points of view. I don’t think I meant anything more than that.18

MacDonald is on to something regarding changing light. The difference between frontal lighting and the use of silhouette early in Snowblind provides a starting point for identifying three-dimensional space and objects. Continuing this thread on illumination, Jenkins reads the film’s overexposures alongside the title and takes them as an example of Frampton’s “examin[ing] the point at which the light becomes so intense that it appears to solidify into an opaque visual presence that is denser than the palpable space it illuminates.”19 In this sense, light impedes one’s “reconstruct[ion],” hence attesting to “ambigu[ity].” In a way, Frampton’s use of overexposure mimics the sculpture’s ability to blot out a view.

Jenkins spotlights a few of the film’s other puzzles. In describing Snow’s sculpture as “a small-scale labyrinthe [sic] or metal maze,” he sets up the idea that there are designs to get out of, or to get lost in. What is true for the film’s pretext extends to the film itself. By noting the “two brief flutters of unfocused light” that come after the film’s title card, and by underscoring the fact that Snow is seen “talking” even though he cannot be heard, Jenkins opens interesting points of inquiry.20 A number of other items that Jenkins does not touch on are also worth pondering:

- the animation-like effect of the shifting light in the quadrants during the film’s early shots

- the positions of Snow’s ears, eyes, nose, and mouth in relation to different blockings created by the fencing’s framings

- the circular intrusions that enter the frame toward the end of the film through the moving of the camera’s lens turret while filming

- the X shape that comes in the penultimate shot before we are returned to the beginning with a second shot of Snow maneuvering a light—Jenkins nicely refers to Snow’s “motion” as “a circular (welding)” one.21

All of these alleyways can produce understanding. They are questions to overcome, or, imitating the game that Frampton may have been playing with his shift from “souvenir” to “hom[m]age,” to come under (venir sou[s]) the spell of.

Snow himself commented on Frampton’s film at least twice in print and also included its final minute as a “Related Document” in his bilingual DVD-ROM Digital Snow (2002/2012).22 In 1971, Snow, discussing his late 1960s sculptures, wrote: “Hollis Frampton made a fine film called Snowblind of one of these works.”23 In 2015: “Hollis Frampton made a very empathetic film of this sculpture, titled Snow Blind [sic].”24 More important than the change from “fine” to “very empathetic,” Snow’s (deliberate?) wrenching apart of Frampton’s title, his reinsertion of a blank space between its fourth and fifth letter, gives but one way to parse what Frampton had soldered shut. Another—Blind’s Now—is resurrected through the power of cinema’s representational forces. What was back then is again. With the restoration of Snowblind, an interchange between two artists from early 1968 will now, hopefully, last for (and lengthen in) always.

Ken Eisenstein is an assistant professor of English at Bucknell University where he teaches in the Film/Media Studies Program. He recently completed his dissertation, “‘Disembering’: The Activity of the Archive in Hollis Frampton,” in the University of Chicago’s Department of Cinema and Media Studies under Tom Gunning and Jim Lastra. His writing on Frampton has appeared in The Criterion Collection’s A Hollis Frampton Odyssey (2012) and in The Moving Image (Spring 2012). He has also published essays on Ernie Gehr for the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève’s Ernie Gehr: Bon Voyage (2015) and on John Vicario in Alternative Projections: Experimental film in Los Angeles, 1945-1980 (eds. David James and Adam Hyman).

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.