In May 1961, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York presented an exhibition titled One Hundred Paintings from the G. David Thompson Collection. A few older artists (Cézanne, Degas, Bonnard) were represented in the exhibition, but the impressive check list, though not comprehensive, was a veritable who-is-who of artists whose main activity was or continued to be in the 20th-century. From Josef Albers to Adja Yunkers, the exhibition offered one-man’s viewpoint of contemporary western painting. Artists especially dear to the collector were represented by multiple works: Braque, Klee, Legér, Matisse, Miró, Mondrian, Picasso, Schwitters, and Wols accounted for more than half of the total, with Picasso’s 12 listed works the most by any artist. Mr. Thompson, in his own introduction to the exhibition catalogue, expressed his thoughts on collectors and collecting, emphasizing his preference for exploring in depth the work of selected artists instead of aiming at a comprehensive survey. Indeed, in several cases, he had acquired more than 40-50 and in a few cases more than 100 works by a single artist. He attributed this to personal taste and individual preferences but also offered more pragmatic considerations as explanation, such as market availability.

By the time of the Guggenheim exhibition, Mr. Thompson of Pittsburgh was not only a nationally but also an internationally known art collector, whose profile had been featured in Life and Time and in several European publications. What was less well known is that by the time the exhibition came to New York after several European venues, Mr. Thompson had already sold nearly all the art to a Swiss dealer, as The New York Times reported just days before the exhibition’s opening. But we’ll have more on this later.

Origins of a Collector

First, let’s start with some general background. George David Thompson was born in Indiana in 1899 and moved to Pittsburgh with his family while still a teenager. He entered Carnegie Tech in 1918 to study engineering. He apparently did not graduate. After stints in New York, he settled in Pittsburgh where, in the next several years, he amassed his fortune in investment banking and later in the steel industry.

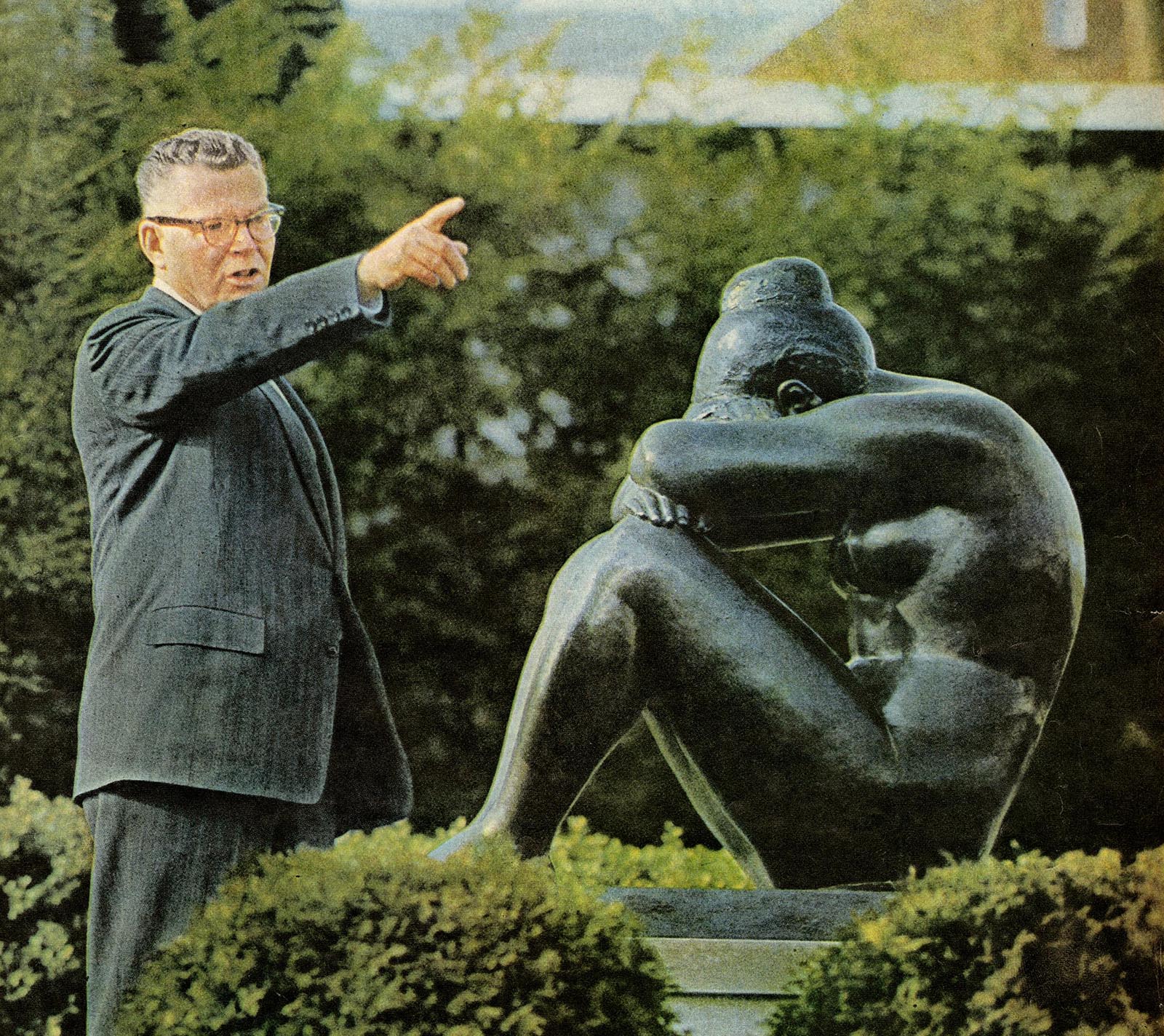

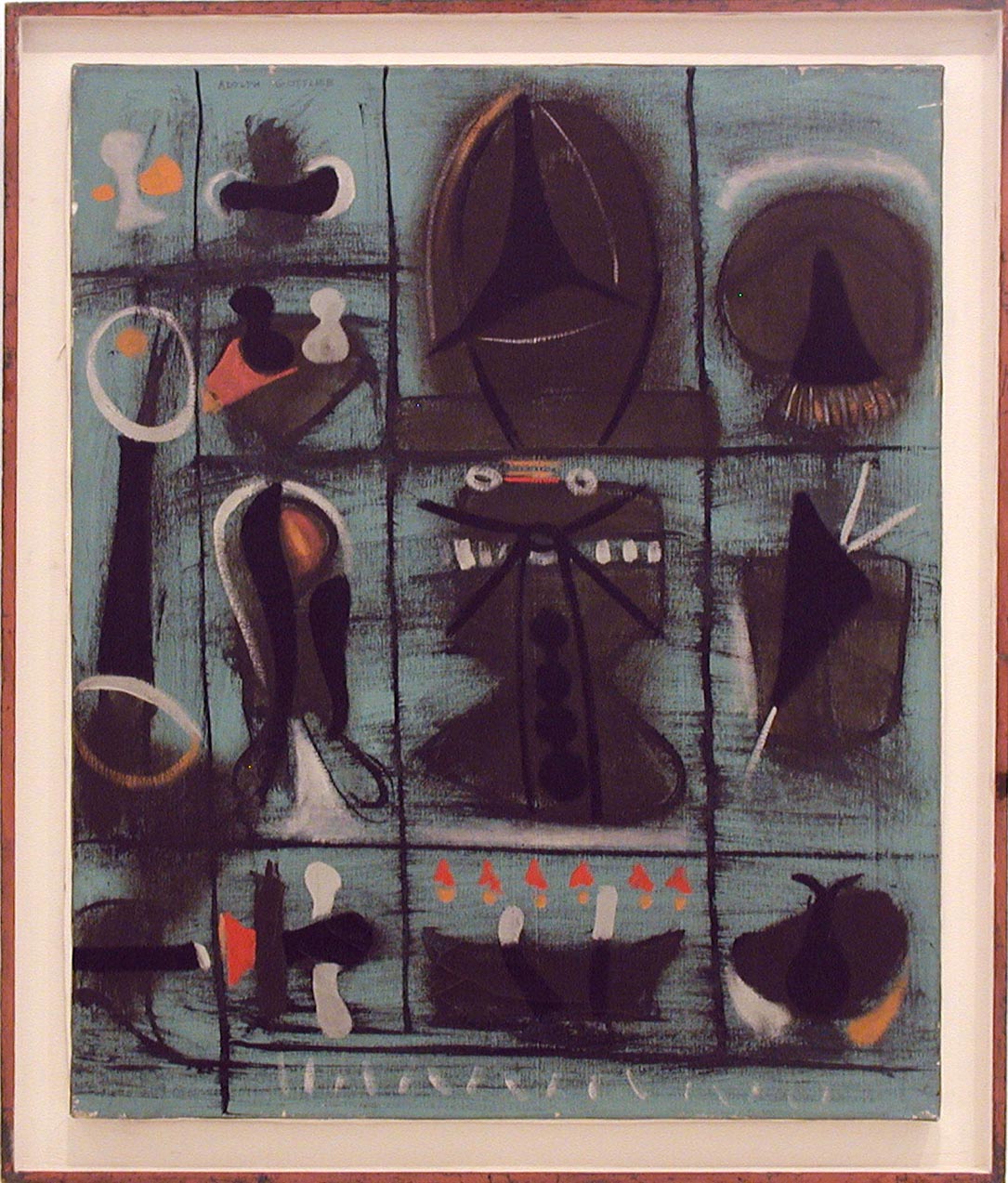

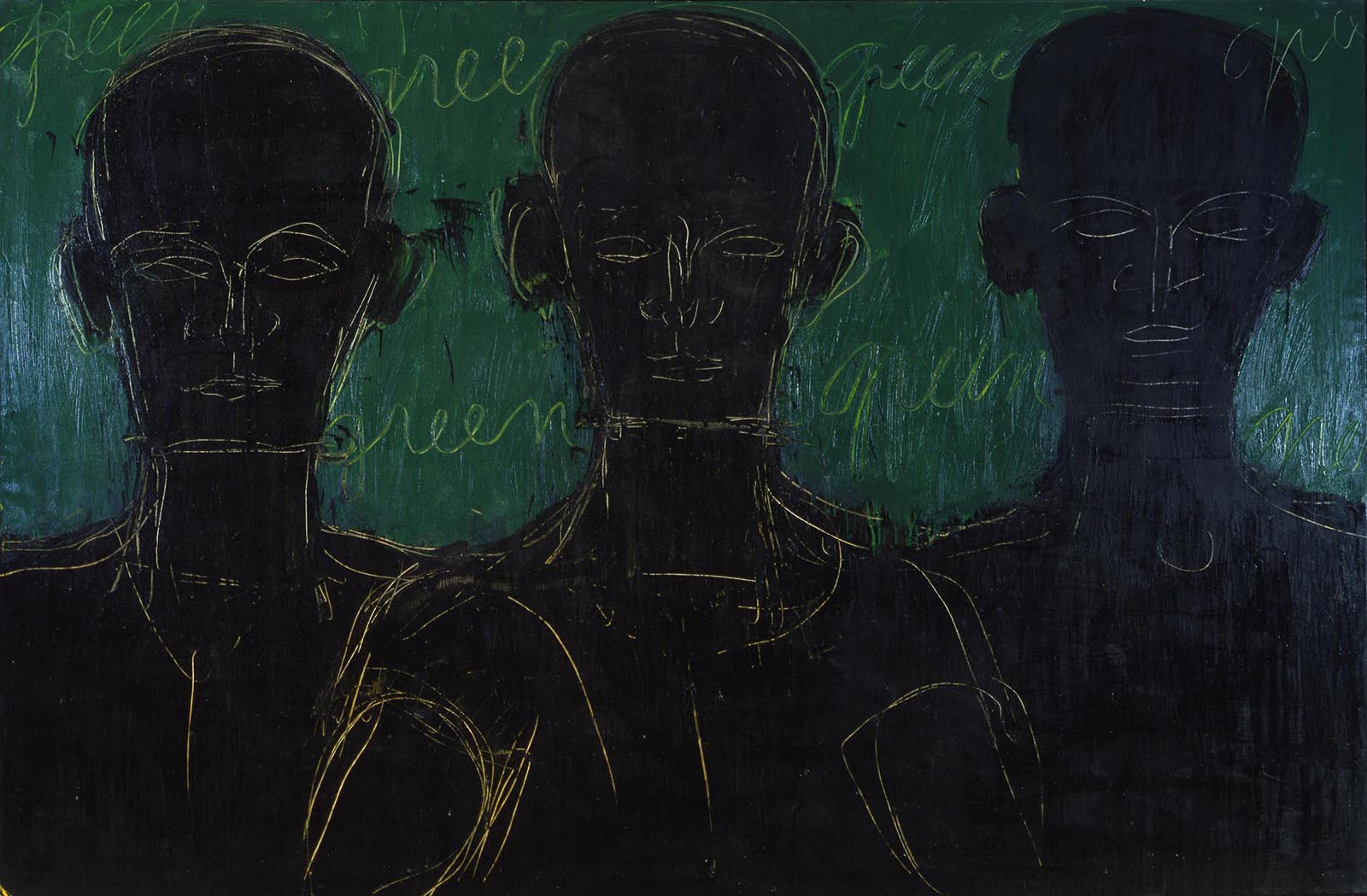

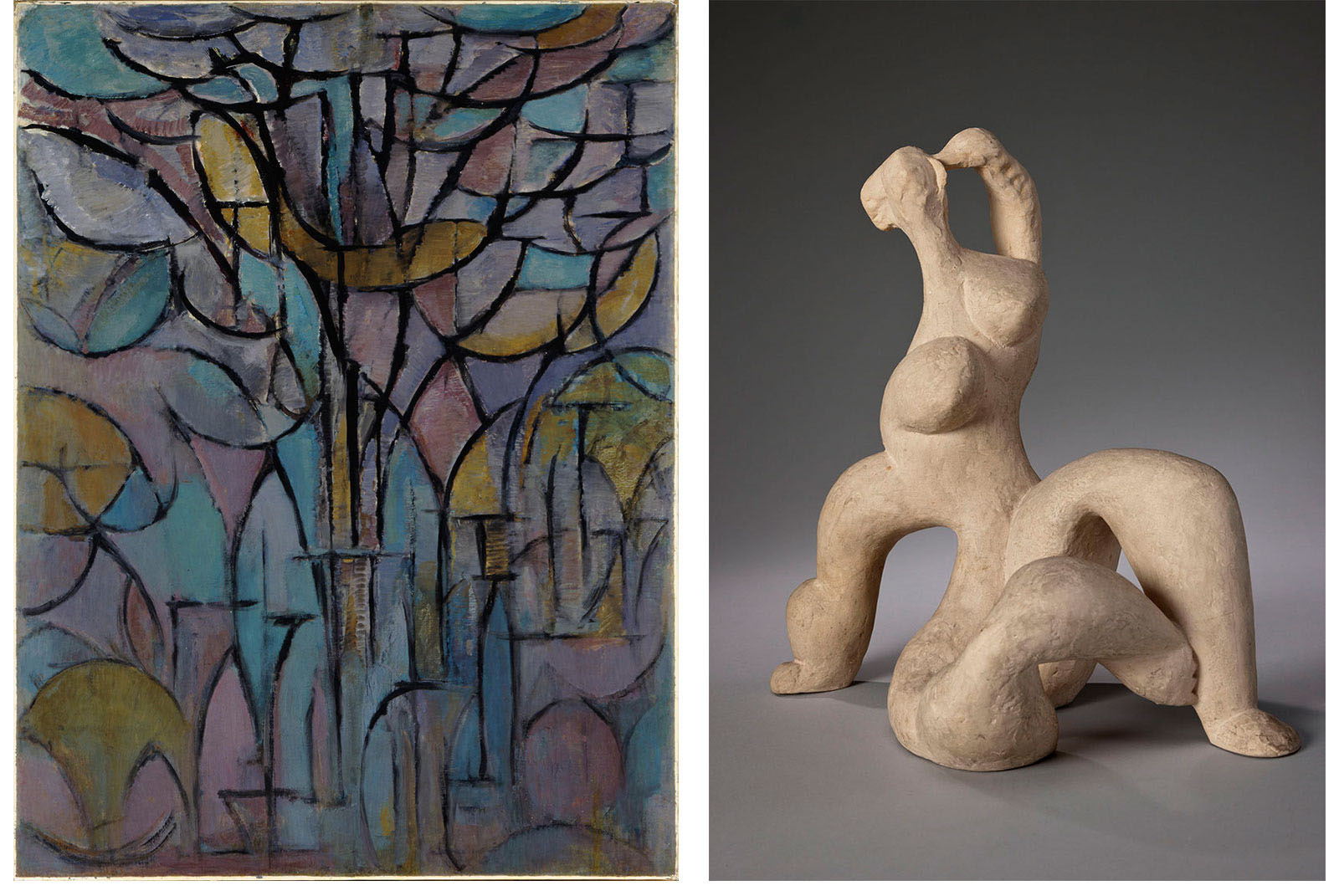

There is no firm evidence about the origins of his collecting activities. It is clear though that, once he began, he collected, increasingly, with a passion and style that verged on ferocity. The first documented purchases, five paintings from the 1928 Carnegie International, already reflect this. Soon, he cultivated the image of a “serious collector” and, as such, his 1933 portrait by Malcolm Parcell shows him surrounded by artworks. Though the early Carnegie International purchases in 1928 and in 1929 were by artists who are now remembered mainly by specialists, by 1936 Mr. Thompson was acquiring canvases by Chagall, Utrillo, and Gromaire. By the early 1940s, he became increasingly involved with his adopted hometown’s premier arts organization, the Carnegie Institute. His first donations were modest: a series of works on paper by Benjamin Kopman in 1942 and 1946. As his collecting activities increased in the late 1940’s—and reached a climax in the mid-1950s—so did his involvement with the Carnegie. Annual reports show that he was generous with long-term loans of works from his collection, made financial contributions for general and specific purposes (such as for a new floor for the contemporary galleries), served as juror for the Carnegie International, and above all donated a number of important works to the institution. Though the pace slowed after 1959, he continued making gifts until a couple of years before his death. In total, he gave the Carnegie more than 100 paintings, sculptures, works on paper, and decorative arts objects, including works by such important 20th-century artists as Adolph Gottlieb, Josef Albers, Jean Dubuffet, Willem de Kooning, Alberto Burri, Jean Metzinger, Carlo Carrà, Francis Picabia, David Smith, Henry Moore, Marino Marini, and Isamu Noguchi. All these works echo the core of his collecting interests. But he also gave 19th-century French works by Jean-Desiré-Gustave Courbet and Adolphe Monticelli, and by 19th and 20th-century Pittsburgh-based artists James Lambdin, David Blythe, and John Kane.

In parallel to his association with the Carnegie, he began his involvement with New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA). Beginning in the mid-1950s he did for that institution pretty much what he was doing at the Carnegie. He loaned artworks from his collection, contributed funds generously for both specific acquisitions and other purposes (in early 1960, MOMA announced that Thompson and another Pittsburgher, H. J. Heinz II, became the first patrons to the museum’s Anniversary Campaign by donating $100,000 each), and gave important works by, among others, Claes Oldenburg, Victor Vasarely, Jules Olitski, Henry Moore, and Pablo Picasso. The latter’s early masterpiece Two Nudes (1906) was Thompson’s gift in 1959 in honor of Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the MOMA’s first director. Thompson was elected Trustee of the museum in December 1960, having served before that on the museum’s Collections Committee. He held both posts until his death in June 1965. His New York friends donated a painting by Victor Vasarely as a fitting memorial to “the first major collector of Vasarely’s work in this country,” according to the museum’s press release.

Thompson’s contributions to the third major institution with which he became associated, the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard, began later and under sad circumstances. Between 1958 and 1960, he donated works by Alberto Burri, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Henry Moore, Karel Appel, and Victor Vasarely, among others, all in memory of his son, G. David Thompson, Jr., who had attended Harvard for two years before his tragic death in an accident in 1958. The reason for the donations was different but the pattern and range of the works selected remained the same.

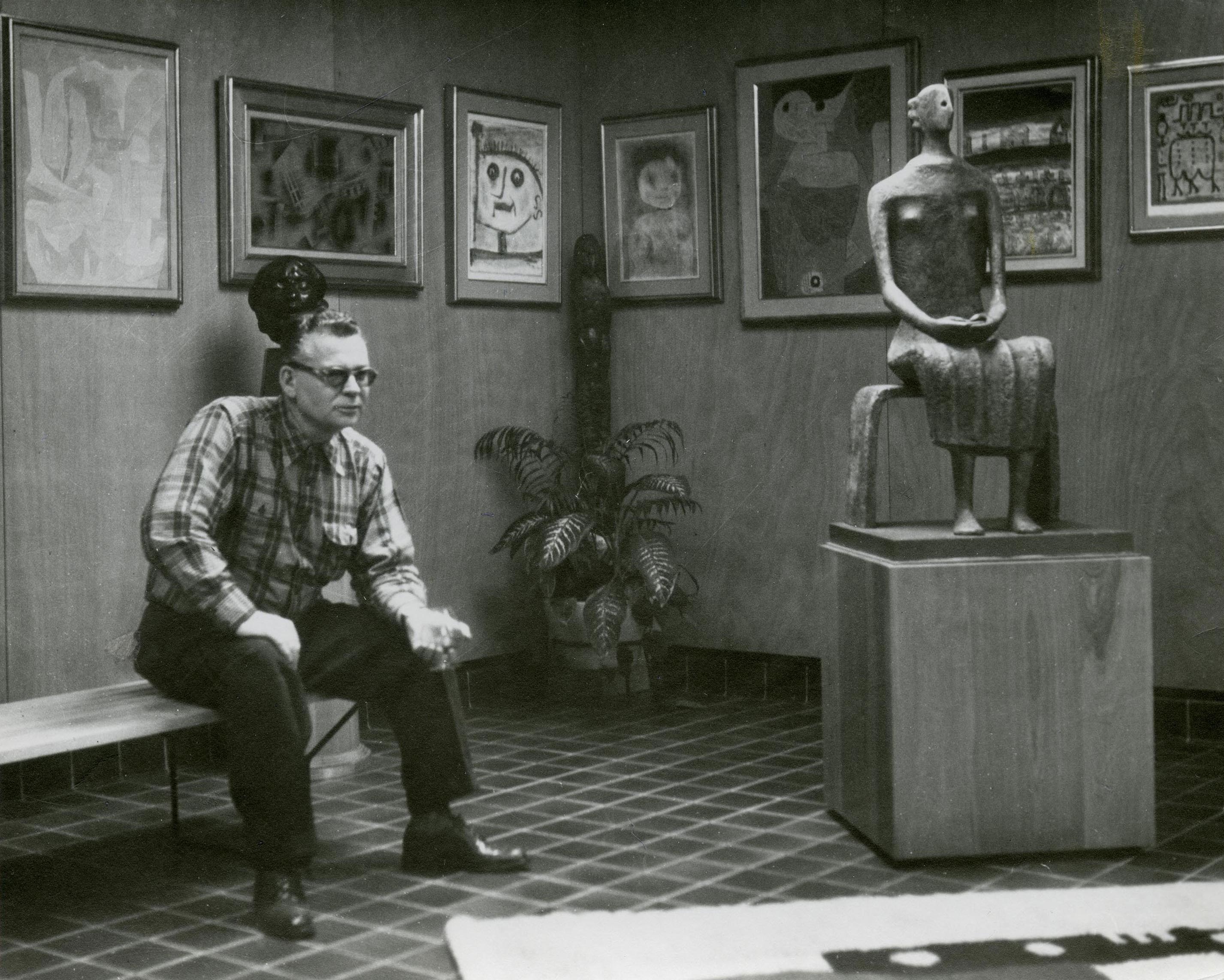

As mentioned above, by the late 1950s Thompson’s collecting had reached its peak. He acquired, traded, sold, sometimes en masse. In doing so, evidence indicates that he pursued what he wanted with a laser focus. So, he negotiated, bargained, made deals, changed his mind, and then proposed new deals to get better terms for himself. He doubtless used all the tools that had made him such a successful businessman, but in the art world this was viewed less charitably. Dealers, especially, hated his hard-nosed style. He probably deserved his reputation for being difficult. But he succeeded in assembling one of the great collections of modern art. By 1959, his suburban Pittsburgh home, “Stone’s Throw,” overflowed with his collection. Art works were displayed everywhere, not just in the specially designed galleries. He enjoyed being his collection’s curator by rotating works on view and by arranging special groupings of multiple works by a single artist and placing them as if “in conversation” with a grouping by another artist. Many artists, for example, Paul Klee, Alberto Giacometti, Fernand Legér, Jean Dubuffet, Piet Mondrian, Pablo Picasso, were represented in exceptional depth. Over the years, Thompson acquired more than 150 works by Paul Klee and about 90 by Giacometti. Giacometti had also painted his portrait.

Pittsburgh’s Loss

Much has been written about Thompson’s 1959 offer, through the A. W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, aimed at keeping his collection in Pittsburgh. All that we know for sure is that an offer was made and that it was turned down. Why it was made, why then, and what exactly its terms were is not known, since no copy of the actual offer has been found. Similarly, the reasons it was deemed unacceptable are not entirely clear, but appear to have been at least in part financial. Whatever the actual reasons, Pittsburgh lost a unique opportunity to keep a truly exceptional collection of modern art and there was extensive coverage of that fact in both the local and national media.

In any event, soon after the offer was turned down, Thompson begun to dismantle the collection. In negotiations in Pittsburgh with the Swiss art dealer Ernst Beyeler, then at the beginning of his illustrious career, Thompson drove a hard bargain. But the two finally reached a deal, and in short order, another, and then yet another. As a result, in just a couple of years, Thompson parted with a large part of his Klee collection, more than 100 works, with a large group of seminal 20th-century works by various artists, numbering in the hundreds, including those in the 1961 Guggenheim exhibition, and finally, with his Giacometti collection, around 90 works. These sales were a major factor in establishing Beyeler’s international stature as a dealer.

Though large parts of the collection were donated or sold by 1961, Thompson the collector was by no means in a retiring mode. To the still considerable collection he retained, he continued to add new works by emerging artists but also by some of his favorite established artists. He also continued to donate works, especially to MOMA, but also with a few more going to the Carnegie.

A bizarre Pittsburgh caper serves as a coda to the Thompson art collection story. In July 1961, during the run of the Guggenheim exhibition, and while the collector and his wife were out to dinner, thieves broke into their house and stole ten paintings: six Picassos, two Legérs, a Dufy, and a Miró. In the process, they virtually destroyed three other works. Based on that and on the way the theft was carried out (works were badly cut from their frames), it was concluded that the thieves were not professionals. The New York Times reported that the collector offered a $100,000 reward for the return of the paintings with “no questions asked,” but that he was too distressed to speak to the press. Instead, Gordon Washburn, the director of the Carnegie’s Department of Fine Arts, acted as his spokesman. Soon contact was made by mail and the collector was instructed to take the reward money to New York and await further instructions; instead, an FBI agent took over, posing as the collector; instructions were indeed forthcoming, which, in caper fiction fashion, involved notes in a phone book at the New York Public Library. Finally, after several months, an unemployed salesman was arrested and all the paintings were recovered, the first, one of the Picassos, in a bus terminal locker and then the other nine paintings in a motel room. As feared, many had been damaged.

Thompson died in Pittsburgh in June 1965. The following March, at Parke-Bernet in New York, 113 paintings and sculptures from his collection were offered at a two-day auction. They included seven Picassos, eight Mirós, four Legérs, four Matisses, and works by de Staël, Mondrian, and Soutine, among many others. The New York Timesreported on the proceedings after each sale. On the first night, some 2,000 people attended and a Braque painting brought the highest amount ($120,000); it was bought by the Ernst Beyeler Gallery, whose owner apparently could use more items from the Thompson collection after the hundreds of works he had bought in the previous six years. After the second night, the paper reported that the two auctions totaled more than $2.4 million and that auction records for 15 artists had been set: for Klee, Miró, Mondrian, and Appel as well as for sculpture by Rodin, Matisse, and Moore, among others. MOMA bought works by Klee, Manessier, Appel, and Miró at the auction. In the museum’s press release about these acquisitions, Alfred Barr recalled that the Klee work, Portrait of an Equilibrist, had been reproduced on the cover of the museum’s first Klee exhibition in 1930 before it was “purchased by the greatest of Klee collectors, G. David Thompson of Pittsburgh.”

The Carnegie purchased but a single work at the auction, Marcel Gromaire’s Midday Rest. With all the glamorous offerings, this was admittedly a curious choice, which was prompted, perhaps, by the painting’s provenance from the 1939 Carnegie International. The museum had also acquired two important works with a Thompson provenance earlier in the 1960s, soon after the collector had sold them to Bayeler: Maillol’s Night, was bought in 1960 and Mondrian’s Trees, in 1961. It is interesting to note that the Maillol sculpture was purchased by the museum with funds provided by the A. W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, which had turned down Thompson’s offer for his collection the previous year.

Later in 1966, after the New York auctions, the Aluminum Company of America purchased 75 abstract paintings and sculptures from the Thompson collection. These were mostly works by lesser known or emerging artists and many had been shown in Carnegie Internationals. Alcoa donated a few of these works, including a terracotta by Henri Laurens and a collage by Kurt Schwitters, to the Carnegie in 1967.

Many years later, in May 1983, what were essentially the last major works from the Thompson collection, 25 in all, were sold at auction at Sotheby’s in New York after his widow’s death. Helene Thompson had kept some important works, including one of Monet’s large Water Lilies (which had hung in the master bedroom at “Stone’s Throw”), as well as works by Klee, Picasso, Redon, Giacometti, Legér, Rodin, Calder, and Arp.

The Legacy

2015 marked the 50th anniversary of G. David Thompson’s death. His legacy as a collector is assured. A major part of his Klee collection remains together at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf. His large Giacometti collection also remains together as the founding group of works that established the Alberto Giacometti Foundation in Zürich. Many other works from his collection are on view at major museums. All three major institutions with which he was closely associated and to which he made his primary art donations currently have several of those works on view, including the Henry Moore sculptures he gave to each of them in memory of his son. Specifically, the Carnegie Museum of Art, in addition to the Moore, has 19 other works with a Thompson provenance currently on view: paintings by David Blythe (2), Patrick Bruce, Carlo Carrà, Jean-Desiré-Gustave Courbet, Willem de Kooning, Arthur G. Dove, Jean Dubuffet, John Kane, James Lambdin, Jean Metzinger, and Piet Mondrian, and sculptures by Aristide Maillol, Isamu Noguchi, Auguste Rodin, and David Smith (2). All these works are enjoyed by the public with or without knowledge of their provenance. Ultimately, this is the true and lasting memorial to G. David Thompson and his collection.

Coda

G. David Thompson collected art, especially modern and contemporary art, for some 35 years, spanning five decades. He bought (and even bartered) works of art from many sources in many places. Throughout that time, his relationship with the Carnegie Internationals was a very special one. He purchased more works from these exhibitions (66 paintings and sculptures) over a longer time span (1928–1964) than any other individual. Though most of these works were additions to his collection, a number were purchased as gifts to Carnegie Institute and, in one special case, the giant Alexander Calder mobile Pittsburgh, now at the Pittsburgh International Airport, as a gift to what was then Greater Pittsburgh Airport. In addition, together with other donors, there were funds contributed so that important specific (but expensive) works could be added to the museum’s collection, such as one of the museum’s iconic sculptures, Giacometti’s Walking Man I from the 1961 Carnegie International.

It was after seeing a preview of that exhibition that Mr. Thompson wrote the letter reproduced below to Gordon B. Washburn, the director of Carnegie Institute’s Department of Fine Arts (now Carnegie Museum of Art.) It is in many ways a remarkable letter, representing many facets of the writer’s persona: the collector, the friend, the champion of contemporary art, the savvy businessman, the museum benefactor. But perhaps, most surprising of all are the comments about the ever-relevant intellectual struggles to understand art, especially the art of one’s time. Coming from a man celebrated for the breadth and depth of his collecting activities—and his rough, know-it-all attitude—it is a startlingly sincere and human outpouring.

This was a difficult time for Mr. Thompson. He had lost his son in 1958. By the time he wrote this letter, he had been turned down on his offer to leave his collection in Pittsburgh, and he had already parted with a large part of that collection. His house had been burglarized and ten important, valuable works were taken—and not yet recovered. But his collecting instinct was very much alive. Of the 66 works he refers to in the letter as possible purchases from the 1961 Carnegie International, he ended up acquiring 22.

Costas G. Karakatsanis has been performing archival research in support of the various functions at the Carnegie Museum of Art since early 2007. A chemist with many years of experience in the management of a research organization at Bayer Corporation, Costas’ work includes investigating the history of the collection, primarily in the area of Fine Arts, with special emphasis on provenance research.

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.