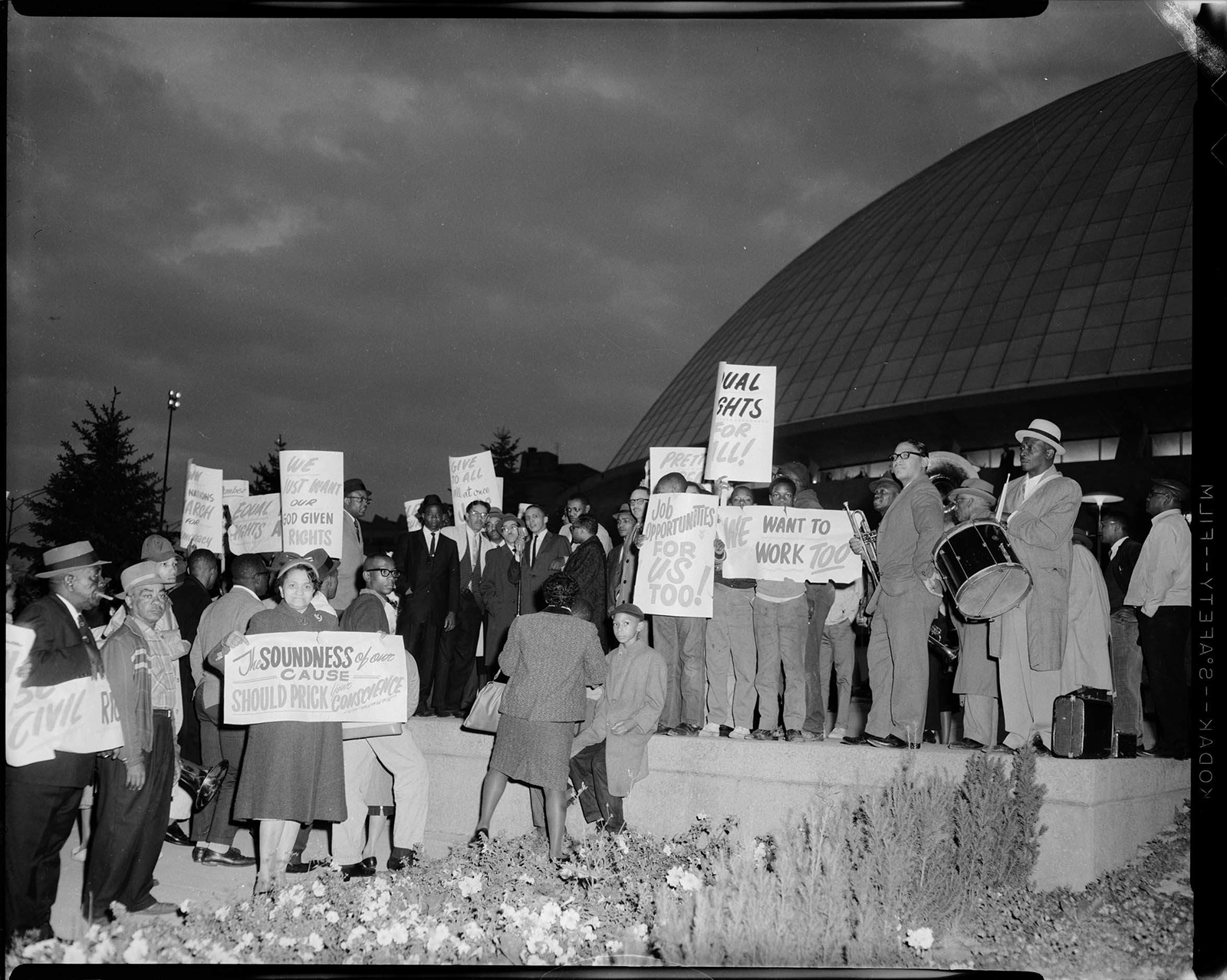

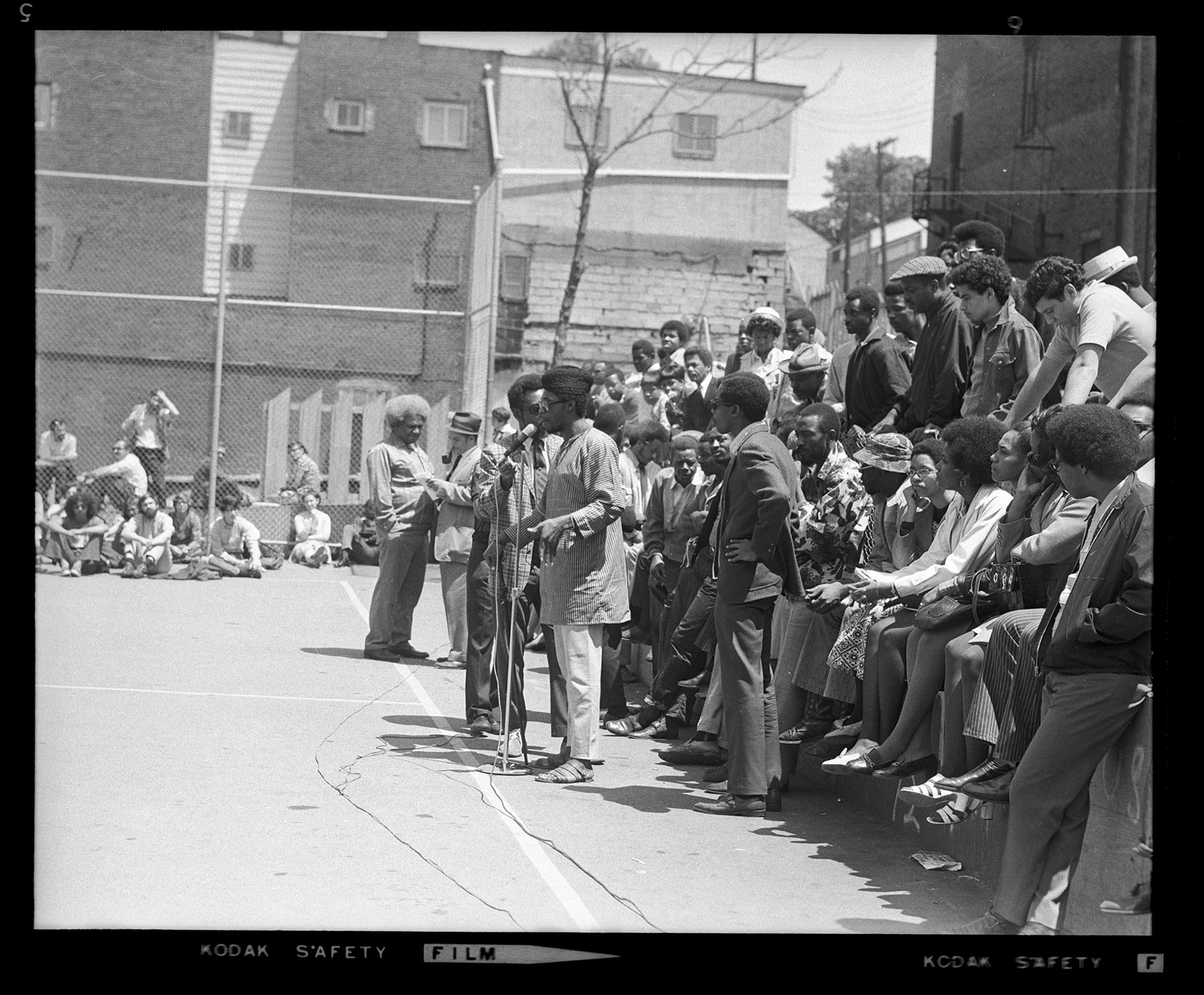

There’s a spirit of resilience that runs through the streets of the Hill District. A hardness that outsiders shy away from but residents embrace. An undeniable mask of determination that don our elders faces from decades of being overlooked and fighting back. One need only glance at the images in Teenie Harris Photographs: Civil Rights Perspectives to understand the magnitude of this grit. Look closer at the crowds holding picket signs in front of a newly built Civic Arena or the protesters marching down Centre Avenue and you can almost hear the faint cadence of a “We Shall Overcome” chant. A call to action that some during that time didn’t hear but others, like community activist Sala Udin, couldn’t seem to ignore.

“Then, all you had to do was walk out the door and the movement swept you up like a wave and carried you down the street with it,” said Udin, who caught the wave at 19, and rode it to the capital to hear Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speak at the March on Washington. At a time when young people were listening to Malcolm X and SNCC and Dr. King to decide where they stood, Udin was trying to figure out who he was relative to this growing movement. “When I heard King talk about the bravery and the sacrifice of the civil rights workers in the Deep South, he answered that question by saying, come do this with your life. And I said yes.” Shortly after, Udin rode the wave further south to Mississippi and joined the effort of attacking legal segregation.

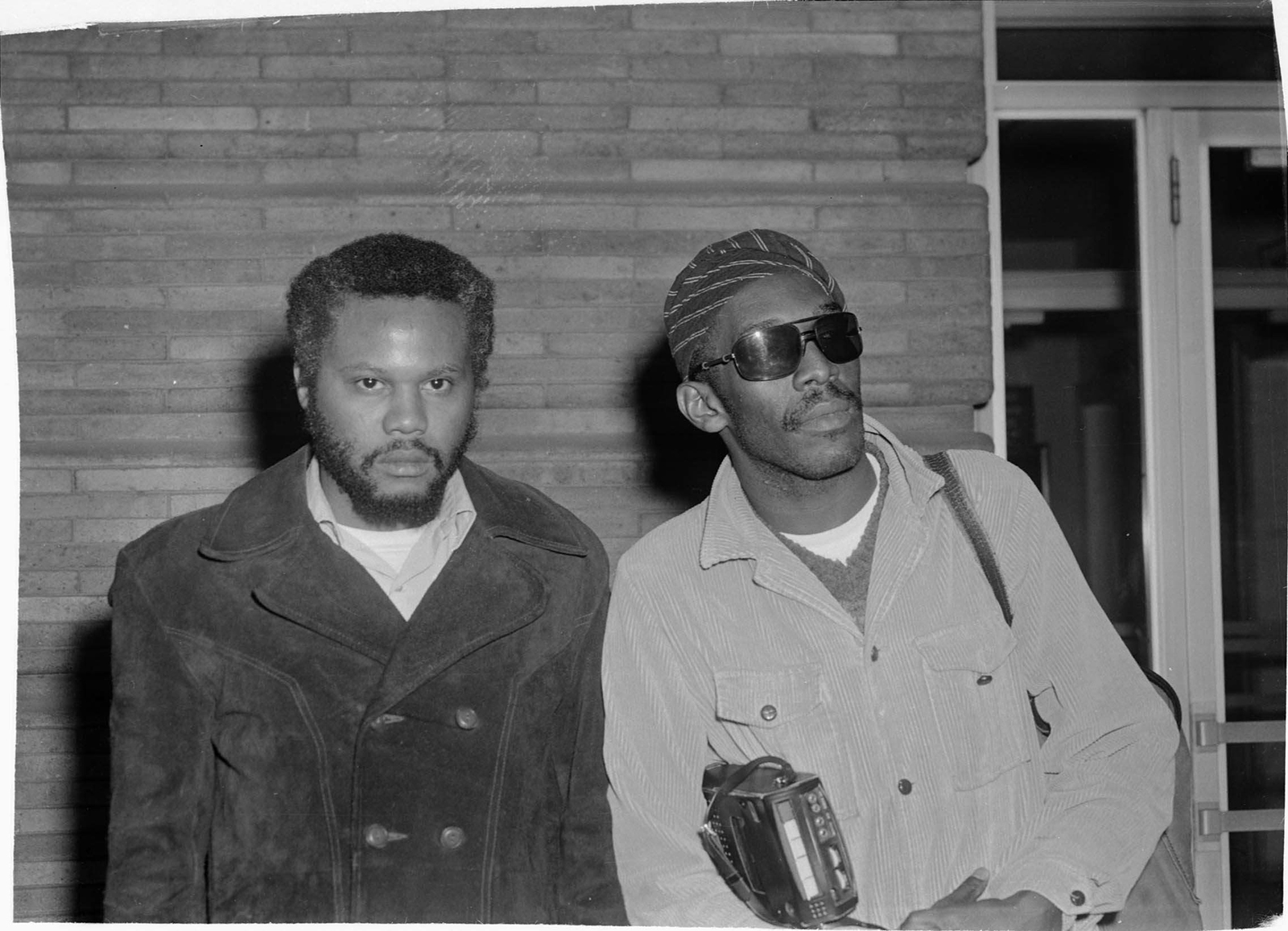

Upon returning to Pittsburgh, Udin channeled his energy into improving the deteriorating living conditions of the communities, the housing issues, the school system, and the relationship between the residents and police. Standing by his side during these battles was his best friend and comrade in the struggle, Jake Milliones. “We were in the Crawford Grill after work every day,” said Udin. “That was the political watering hole.” Milliones had no personal interest in a political career himself, according to Udin. So with other community leaders, they fought to get his wife, Margaret Milliones, elected as president of the Pittsburgh school board. “When Margaret died…we had to convince Jake to enter politics. But Jake quickly became one of the strongest leaders the school board had ever seen.” Under his presidency, Pittsburgh schools became national models for success.

Following his 13-year term as school board president, and after years of fighting for district voting for city council elections, Milliones became the first district-elected representative from the Hill District. An advocate for quality housing, equal opportunity employment, drug rehabilitation programs, and senior living and health initiatives, Mr. Milliones was recognized as one of Pittsburgh’s foremost civil rights champions before his death in 1993.

No More False Promises

The Akan of Africa have a spiritual belief of Sankofa, or “Go back and fetch it,” which means we must learn the lessons of our past to ensure a positive and progressive future. If the Hill District community has taken nothing else from the flawed revitalization plans it suffered in the fifties, it has learned not to blindly trust developers and city officials who make false promises. In the spirit of Sankofa, current community leaders are fighting to insure that the city keeps Hill District interests in mind during the new redevelopment projects.

As President and CEO of the Hill District Community Development Corporation, Marimba Milliones is one of these leaders. Picking up where her father left off, Milliones devotes the majority of her time fighting some of the same community issues he faced years earlier. She describes her work as one that ensures the new vision for urban renewal translates into something realistic and beneficial to both future and current residents.

“As long as issues of disparity continue to impact us and our communities, we must continue to address the problems and solutions of those issues,” said Milliones, who learned this lesson early in life growing up in a home with activist parents. She credits her mother and father for her proclivity to fight injustices and her personal connection to the plight of the Hill District, and fondly remembers standing in picket lines and attending protests on weekends while other teenagers were going the movies and mall hopping. But Milliones isn’t convinced that this is the life her father would have wished for her.

“I think he would be proud. But I think that it’s an assumption that my parents would have wanted me to spend my life like they spent theirs. His perspective may have been, ‘I’ve spent 50 years doing this work Marimba… you should have been a lawyer or a doctor.” Milliones, however, is certain that this is the path God chose for her, and that her father would appreciate and have a deep understanding of the work she’s doing. Still she confesses, “Frankly, if my parents hadn’t died I probably wouldn’t be doing this work. I would have made the assumption that it was being handled by them. And I probably wouldn’t have come back home.”

Passing the Torch

Like Ms. Milliones, I am a proud Hillbilly. My grandparents, parents, and extended family are all products of the Hill District, so I had always played with the idea of writing a novel that would keep the stories of the neighborhood alive for future generations. It took me a little longer to make the journey, but when residents were, once again, displaced and ostracized from the community in the name of redevelopment, the need to preserve the legacy of the community pulled me back home as well. That’s when I started writing Cozy Lee Luke at the Crossroads of the World, a historical fiction novel set in the Hill District during the golden era of jazz.

While working on this book, I often turn to Teenie Harris’s photographs for inspiration and am both fascinated and disturbed by how the problems of our past come back to haunt us through the lens of his camera. Who could have imagined that 50 years later we would still need to argue the case for employment opportunities, business opportunities, and affordable housing for both new and lifelong residents—especially when that development takes place within our own communities? Who could have imagined that we as a society would still be in a place where corporations had to be convinced to consider these issues for the sake of human rights and responsible civic planning? It’s as if the shortsightedness of Pittsburgh’s urban renewal programs of the 1950s—which led to the destruction of the lower Hill—has already been forgotten.

As a young boy Sala Udin was raised in the lower Hill, the area where the Civic Arena rose and fell. When asked how he felt about the recent tensions over a plot of land that, for many residents, represents what has and could go wrong with urban redevelopment, Udin only smiled. “Agitate, agitate, agitate,” he repeated. “That’s what Marcus Garvey said. Freedom is a constant struggle. It’s not an overnight struggle, not a one-week struggle, but a lifetime struggle. That land sat as a parking lot for half a century. That’s how long it took to get to a point where some development will occur. And we have to continue our fight to participate in that development.”

Heeding this advice, I will do my part as an artist to keep the spirit alive. To pass the torch. To incorporate the battles and the triumphs of the Hill District into my work. So that when people listen to the stories of my oral history collection, or when they read my literary work, they will hear the faintest cadence of a chant—We shall not be moved… we shall not be moved—floating above, beneath, and between the words.

And continue the fight to be heard.

Yvonne McBride is an author and oral historian based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She is a Flight School Fellow and a two-time recipient of the Advancing Black Arts in Pittsburgh Grant from The Pittsburgh Foundation and The Heinz Endowments. McBride is currently working on a historical fiction novel set in the Hill District during the jazz era.

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.