As a kid growing up in El Paso, Texas, the Cadillac was considered the car that old white people drove. Nobody that I knew owned one or even wanted to. In those days we lived at Fort Bliss military base, so no G.I. could afford a Cadillac had they wanted one. If any of those enlisted men once posed beside that luxury car back in their hometowns, those youthful aspirations were long since forgotten, or rather wiped away by the indoctrination of boot camp. For the men of Fort Bliss no longer held the identities from whatever town, city, or neighborhood they hailed from.

It wasn’t until my stepfather decided that our family was living in sin that I saw my first Caddy. The year was 1982, I was turning 12, and my mother had just given birth to my youngest sister. Tyrone, my stepfather, was a mean man made even more sinister by his Army experience. He had been horrible to my mother for years, yet she always stood by him, always defended his behavior. In response, I grew up thinking it was normal to fight like rabid dogs. Family lore tells of more than a few affairs, but only one landed my stepfather in a disciplinary hearing with a commanding officer; only one landed us at Unity Missionary Baptist Church; only one of his dalliances landed me struck with awe after my first encounter with a Cadillac.

It was beige, with a dark-brown rag top, the chrome gleamed like a winning horse’s teeth. The whitewall tires trumpeted themselves as the whitest white you could ever attain. Whiter than all of the South, whiter than this Jesus that Tyrone believed would fix his dysfunctional family. There was no doubt who the car belonged to. It was in a reserved parking space right next to the side door of the church. I remember my mother yanking my arm as I marveled at it for she too wanted the redeeming light of the church, she too wanted to lay her burden down.

I don’t remember much about that first service other than the music, but I was struck by how the congregation gathered around the pastor, Reverend O.I. Kirk, owner of the majestic beige Caddy. I remember thinking how strange it was to have never seen that kind of car before. I wondered if only the holiest of men got to drive them, while the rest of us devils languished in Fords, Pontiacs, and Oldsmobiles.

Over the next year, Tyrone and my mother threw themselves into church life, attending every service, fellowship, and prayer meeting. They had even entered into the church’s deacon training program, and increasingly the pious front became a reality, so much so that I felt like I was watching myself living with a whole new family, and I found myself missing the fights, drinking, and laughter that punctuated so much of my childhood till then.

My mother decided to let me visit my birth father that summer in Cleveland, so I boarded my first plane and headed to the city she had run away from. I had never met my father before and didn’t really know what to expect, as my mother never much talked about him. The few times she did, Tyrone would lose his temper and a fight would break out. I could never fully understand why the mere mention of my real father sent him into such a rage that he would punch my mother and whip me. But as I stood by baggage claim waiting for my father, I decided not to mention it to him. It would only cause more trouble for my mother and I wanted to protect her. After nearly two hours, a short and stout man walked up to me with the biggest grin I had ever seen. It was the first time I had ever seen my father.

When we reached the airport parking lot, that’s when I saw it: a 1982 Cadillac DeVille. It was nicer than the reverend’s Cadillac. But more importantly, it was my father’s. As I sank into the plush leather seat I knew why Tyrone hated my father. He hated my father for what he had. He hated that as he struggled, taking orders and making a shit wage while feeding three kids and a wife, my father was in Cleveland, dressed in the finest clothes and driving a preacher’s car. I even remember asking my father if he was a preacher, only to have him laugh and say: “You ain’t got to do no preacher hype to get one of these. You just gotta work hard and go get one.”

When I asked my father where he worked, a dogged pride permeated his response: “I’m in the Ironworkers Union young blood, I’ve been at my job at LTV Steel since before I met yo’ mama.”

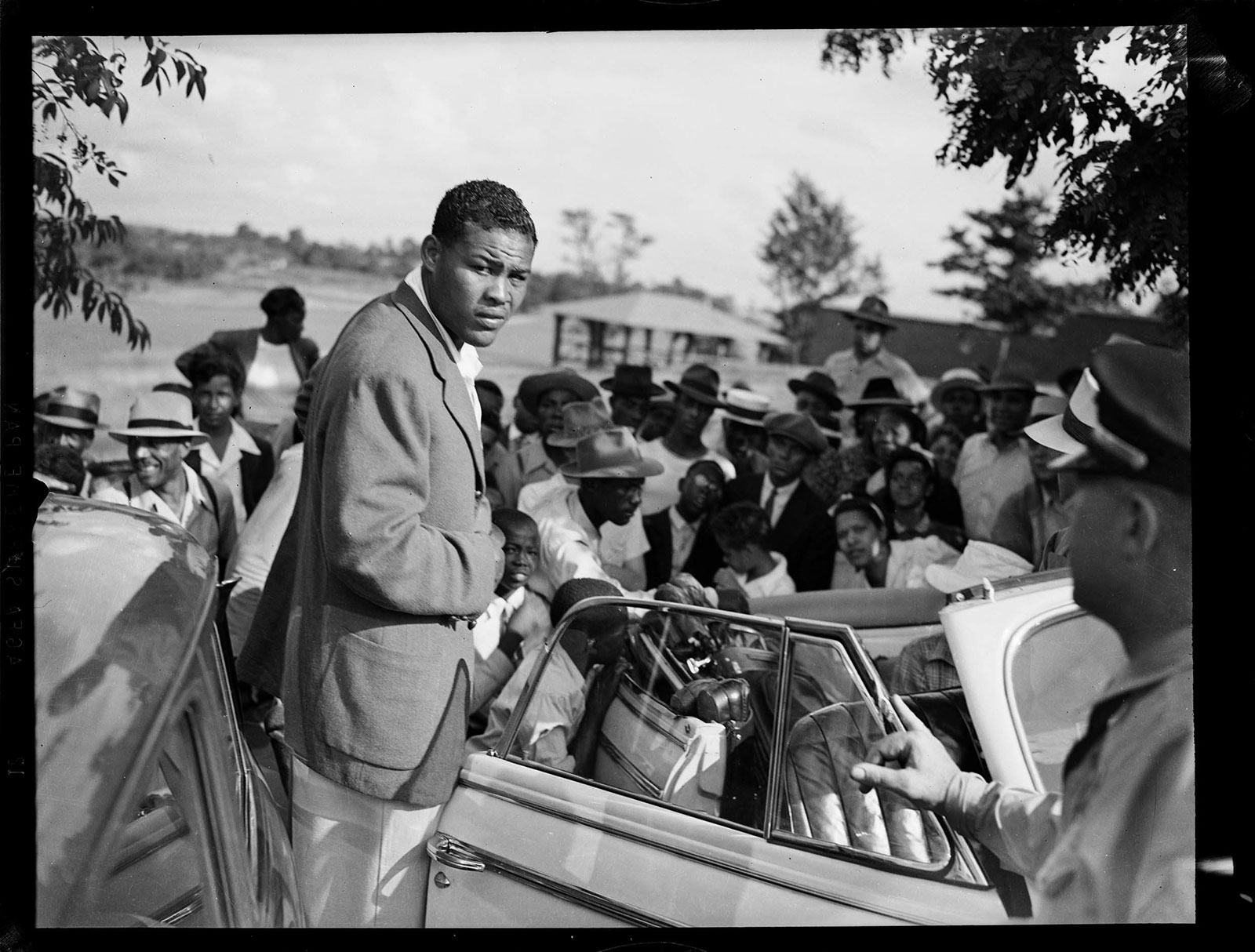

The pride that I heard in my father’s voice that day is why I am writing this essay, for Teenie Harris captured these flickering moments of possibility over the course of his career as a photographer for the Pittsburgh Courier. His images expressed the duality of black life, revealing that the same frame could hold a million razor cuts tucked in the way, way memory of Joe Lewis’s eyes, and that smoldering, larger-than-life persona that made him our champion. Or permanently freeze the charismatic smile of bandleader Billy Eckstine as he stepped out of his gleaming Cadillac, mid-century Pittsburgh still alive in the backdrop. No other celebrated African American photographer could speak to the very essence of black life like Teenie could. And often times it was not the people he documented, or the historic events that he covered, or the crime scenes he witnessed from behind his lens that spoke to our collective aspirations, trials, and otherworldly misery—it was his grand photographs of cars. For these automobiles became the symbol of us making it, the four-wheeled linchpin of our maleness; the material essence of our limited access to the American dream; the muddied road toward what was possible; the dreams that we as children allowed ourselves to entertain. The automobile was the coveted example of freedom. Still is.

It’s been 17 years since Teenie passed and we can still hear the thump of our beatific selves translated out the trunks of cars, sitting low on rims freshly polished. The news full of our drive-by genocide, the dream has turned to collusion, we imitate the savage that brought us here in chains. We mimic the Poplar tree and catch the nightstick fury of this country’s disregard of black bodies. Our children no longer dream of the Cadillac, no longer speak of freedom for they have seen a 12-year-old boy gunned down for playing in a park, have watched friends and family torn apart by police bullets even when hands are raised in compliance to authority. No, they no longer dream of good factory jobs, unions, and Sundays dressed in magic. They dream of fire. Let it burn oh Lord, let it burn.

RA Washington is the author of 26 books, most recently CITI (Red Giant Books, 2015) and Night in a Fair Republic: New and Selected Poems (Hydeout Press, 2015). He is the founder/owner of Guide to Kulchur: Text, Art & News, an independent bookstore and small press publisher. He lives on Cleveland’s west side with a bunch of awkward punks.

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.