A Note to the Reader

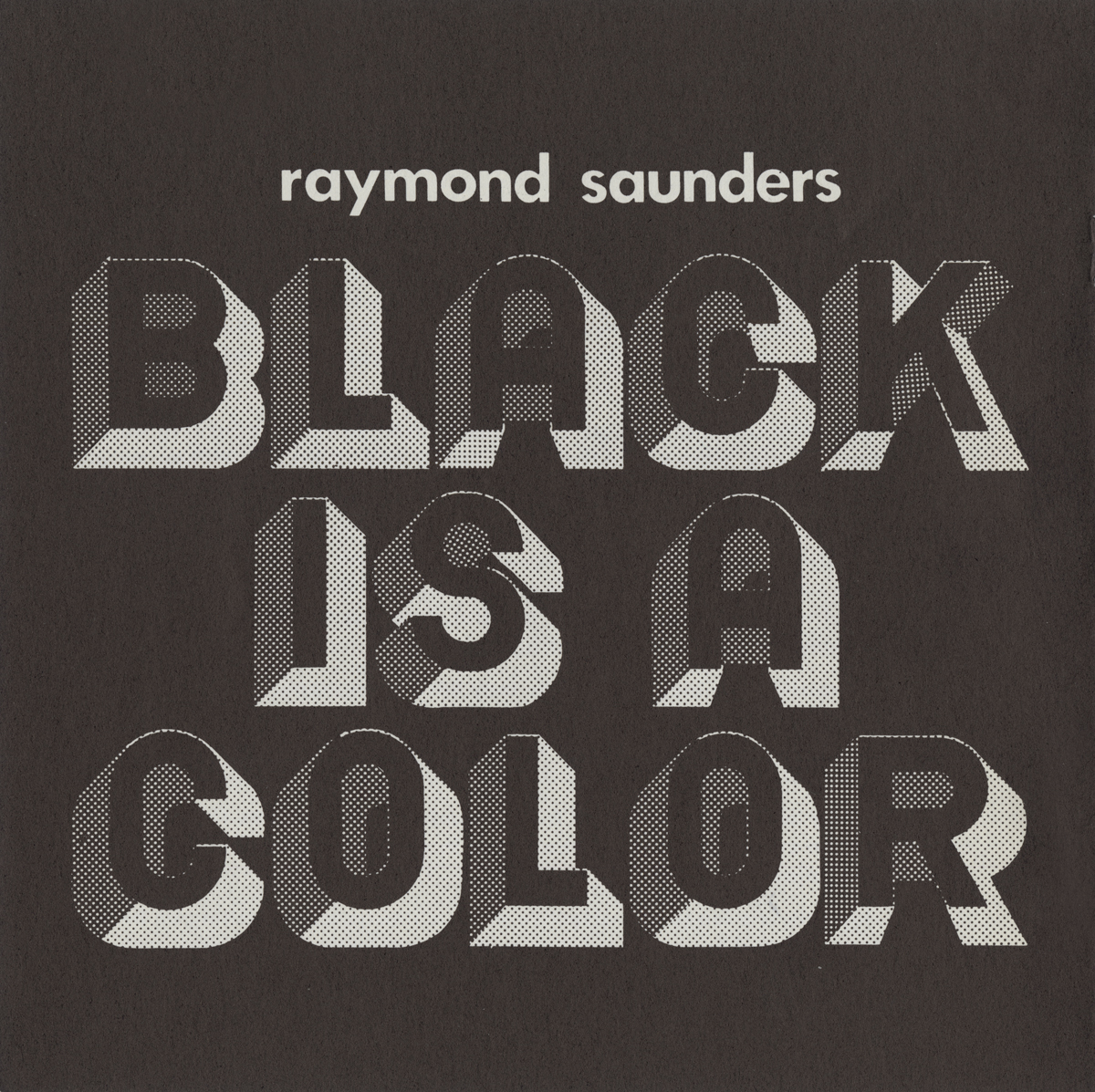

The following essay by Raymond Saunders was originally published as a pamphlet by Terry Dintenfass Gallery in New York on the occasion of a solo exhibition by the artist in 1967. It is a direct response to an article by writer Ishmael Reed that appeared in the pages of Arts Magazine earlier that year. Saunders’ essay is reprinted here in its entirety and in its original typographic expression as intended by the artist.

It is reproduced with permission of the Estate of Raymond Saunders; © Estate of Raymond Saunders. All rights reserved.

Black Is a Color

by Raymond Saunders

arts magazine published an article (may, 1967) in which it claims that poet-novelist ishmael reed has “documented” the “explosive black arts movement.” mr. reed himself, if the title he chose denotes his aim, assumed the heroic role of black artist’s champion, hipping it through the musty debris of hypocrisy and lies, into the clear light of newly-daring truth, where a spade can at last be called a spade.

yet, after this one man takes it upon himself to call it a fucking shovel, we know nothing more about the spade at the end of his tirade than we did at the outset.

what’s he trying to prove? all he says has been said before, with the same pitiful and dangerous inadequacy. on the one hand, he seems to be trying to support the black artist’s cause, while on the other he lumps black artists, of which he names a mere handful, into one bag and throttles them with a string of almost incoherent hippishness.

more flip than hip, his diatribe may have been meant to give the black artist a lift, but glib and shallow as it is, the net result is far more degrading of the black man and artist than any mute rejection by a museum selection board (one of mr. reed’s bones of contention).

using hip-talk as a kind of tribal mumbo-jumbo, he sets the black arts outside the current of art as a whole, and in doing so he does the black artist a grave injustice.

hip-talk is a language, effective when it illustrates something of human substance, but where it is the substance of this subjective, emotional outburst, it all seems as futile and paradoxical as the demonstrations of those “half-way” young hippies who advance on their opponents shouting: “love, love, love!” while pelting them with rotten eggs.

who’s supposed to be saving who? mr. reed appears to propose that the black arts should save america, as though the act of salvation were a function of some rarefied preservation hall, and the black artist a species of new orleans entertainer, who can “make america swing again.” but let’s face it — when has america ever swung? and why should it be the black man’s responsibility?

this is a pseudo-messianic concept that mr. reed is free to subscribe to, but what makes him think he qualifies as a spokesman for black artists? is it because he’s black — or because he’s an artist? he doesn’t seem at all sure in what measure the two are one, and the ambivalence of his approach renders his spade-calling curiously unconvincing.

apart from a disproportionate quotation from leroi jones, mr. reed’s “documentation” of black arts is famishingly sparse. black music is harnessed to archie shepp, albert ayler, and sun ra, latching on to examples of a certain discernible success, but what of the countless unsung but brilliant black musicians whom mr. reed blithely ignores? and, though he uses an interesting photograph of sun ra to illustrate his article, mr reed gives mere caption-mention to the photographer himself, and focuses no attention whatever on the growing band of vital black photographic artists in america, of whom charles shabacon is just one member, albeit a highly creative one.

in approaching so vast a subject as the black arts, whose scope far outreaches the limits imposed upon him by the editorial requirements of arts magazine, it would appear that mr. reed bit off more than he could chew. but this is no excuse for launching into so sadly haphazar and scrappy an exposition, while still retaining an ambitious title-promise beyond his capacity to fulfill.

what is more disturbing, however, is mr. reed’s assumption that success must be equated with material gain; that uptown and money spell success for all. uptown is no “open-sesame” to artistic fulfillment, nor is money, as mr. reed appears to believe. uptown is the art marketplace, but who says it’s the art scene? what are we dealing with here, anyway — art or a popularity contest?

material success is extremely desirable, but it’s a dangerous criterion by which to measure artistic achievement. mr. reed seems to have fallen into the trap, adding insult to injury by dragging art through the mud of socio-political antagonism. The ‘we is all’mericans’ bit, to which he so strongly objects, is beside the point. ‘we is all artists’ seems more akin to the subject.

i am an artist; examples of my work can be seen in american museums; i have been the recipient of national awards; i have just enjoyed the ‘privilege’ of my fourth one-man show at an uptown gallery (reviewed p.60 of arts magazine, may, 1967); and i also happen to be black. i fail to see any profound significance in the mere conjunction of these circumstances. yet, if one is to take mr. reed’s sweeping statements as criteria, it must be assumed that i am a phenomenal success. bullshit!

what are the true criteria for success, in terms of the individual artist’s aspirations? is he committed merely to the realization of a stereotyped image of the artist who’s “arrived,” crowned with the laurels of popular acclaim; assured of a constantly re-plumpled bankroll and entree into the inner sanctums of madison avenue (which seems to be mr. reed’s contention), or is it rather that the artist is committed to respond to the unending challenge of his very nature as a creative person, and to discover the depth, width, range of his own unique vision as an artist, and, hopefully, as a human being?

i’m not here to play to the gallery. i am not responsible for anyone’s entertainment. i am responsible for being as fully myself, as man and artist, as i possibly can be, while allowing myself to hope that in the effort some light, some love, some beauty may be shed upon the world, and perhaps some inequities put right.

every creative person is subject to periods of profound discouragement, when denied recognition of the vision he embodies in his work. the denial seems to constitute a rejection not only of his work but of all he is striving to be. in his angry rebellion, he may well lash out at the first apparent obstacle—which can easily take the form of some highly publicized social or political defect in his environment. it’s a plausible explanation for some deadlock in his progress. it can be a very real one too, in which case his anger is perfectly valid. but when anger, a human reaction, gets syphoned off into serving merely as a political expedient, it is robbed of genuine humanity, and is useless as inspiration to the artist as a man.

some angry artists are using their arts as political tools, instead of vehicles of free expression. using his art and his anger in such a way, the artist makes himself a mere peddler, when he might be a prophet.

every artist, regardless of his skin color, may suffer from the vagaries of museum selection boards. confusing this age-old problem with questions of race is just casting about for a scapegoat, when the real culprit — the dragging, grinding mechanism of american social and cultural awareness gets clean away, unchallenged. all americans are culturally deprived, not just black americans.

the prevailing system repeats its sterile terms of reference for success (to which mr. reed himself, oddly enough, seems to subscribe). the image that fits into those terms may not easily be stretched to include the black artist, particularly if he claims his blackness as the reason for his achievement. but the basic question is, does the black artist, or any other artist for that matter, want to mold himself to this prescribed, but worn and shabby image in any case?

the image itself is the result of distortions in human society, stemming from deprivation, but this is the plight of every man. the underdog, the low man on the totem pole in this society, will continue to suffer because of the blindness and selfishness of society’s leaders. this is nothing new, and what has this got to do with art itself, or the real quality of the artist?

art projects beyond race and color; beyond america. it is universal, and americans — black, white, or whatever — have no exclusive rights on it.

when are americans going to wake up to the fact that america is not the world, nor the cultural center of it. there’s a big, big world out there, where people of all colors are living; yearning, competing, suffering, reaching out (and some succeeding) with every turn of the earth.

no one can honestly deny the existence of discrimination and oppression against black people (and black artists, by extension) in america, but the black man is not the only human being ever to have suffered these ills. counter-racism, hyper-awareness of difference or separateness arising within the black artist himself, is just as destructive to his work — and his life — as the threat of white prejudice coming at him from outside.

pessimism is fatal to artistic development. perpetual anger deprives it of movement. an artist who is always harping upon resistance, discrimination, opposition, besides being a drag, eventually plays right into the hands of the politicians he claims to despise — and is held there, unwittingly (and witlessly) reviving slavery in another form. for the artist this is aesthetic atrophy.

certainly the american black artist is in a unique position to express certain aspects of the current american scene, both negative and positive, but if he restricts himself to these alone, he may risk becoming a mere cypher, a walking protest, a politically prescribed stereotype, negating his own mystery, and allowing himself to be shuffled off into an arid overall mystique. the indiscriminate association of race with art, on any level — social or imaginative — is destructive.

isolationism: us-against-the-world, is stultifying. it undermines the very emancipation the black man so deeply desires, and to which he is entitled. us-coming-out-into and becoming-a-part-of a wider reality — becoming what we really are — is what will truly free us.

in america, black is bound to black not so much by color or racial characteristics, as by shared experience, social and cultural. this is the same in any rarefied social (or racial) enclave, but “no man is an island, entire of itself.” the artist deals with the human condition. he is “involved in mankind.” this is as valid for the black artist as any other. he uses his heart, his eyes, his mind as interpreters of his own deep vision of himself, and the world as it is reflected in those depths.

if he wants to get out there; if he really wants to know, there is nothing that can stop him. a hell of a lot depends upon his curiosity and his own determination. the artist can only realize himself through active effort to be what he really is.

both as artist and as human being he can learn to channel his energy, rather than expend it in futile protest. he has to send his mind, his emotions, his eyes ranging across the whole field of vision open to him, probing its boundaries to find where he can push them further and further out.

the creative imagination is his channel, but it has to be dug (painfully slowly sometimes, as it has been throughout history) through the resisting barriers of established convention; then it can bring its new, irrigating force to the parched and thirsting desert of cultural and spiritual backwardness.

but the artist doesn’t exist for the sole purpose of changing the world. each artist has to do for himself what is necessary for his own development, fulfilling himself as an individual, not as one of a herd. he has to enter into the total experience of himself and his vision, which transcends the cramped boundaries of any stereotype—angry or otherwise. it is a risk, but life is full of risks, if you’re going to live at all. living is being hurt, happy, sad.

humility is frowned upon these days, yet the very immensity, complexity and universality of art should be a reminder to the artist that he cannot be the be-all-and-end-all. the pressures and oppressions the black man has so triumphantly endured could be translated into positive strength that will persist in the teeth of rejection, refusing to be eliminated. this goes for the black artist too.

in order to be recognized and accepted, does the black artist have to depend upon the uptown critic or the politico-sociologist to define the meaning of his own experience? it is high time that the black artist make his own rejection of misguided, inadequate —if not out-and-out dishonest — interpreters of his condition. from the depths of his own integrity he has to believe in his capacity to distinguish the real from the false — and to recognize manipulators when they try to use him.

racial hang-ups are extraneous to art. no artist can afford to let them obscure what runs through all art — the living root and the ever-growing aesthetic record of human spiritual and intellectual experience. can’t we get clear of these degrading limitations, and recognize the wider reality of art, where color is the means and not the end?