For over 20 years, Pittsburgh residents Karl and Jennifer Salatka have been active members and voices at Carnegie Museum of Art. While today they possess a collection vibrant with key modern era artists and their own unique personal aesthetic, neither of them began the journey with a background in art history or even a familiarity with the Museum of Art. Avid curiosity and a self-motivation to learn have guided the Salatkas towards embracing a newfound passion for art.

Both Karl and Jennifer are naturally drawn towards the sciences. In fact, they met while Karl was attending medical school at the University of Pittsburgh and Jennifer was working as a nurse at Montefiore Hospital. They admitted that while growing up they had never visited the Museum of Art, despite having been at Carnegie Museum of Natural History numerous times. Thus, the sincerity of their appreciation for the works they own is even more pronounced given their distance from the art field. Starting their art appreciation from the ground up as adults has only better enthused them. Their dedication has involved forming close relationships with Pittsburgh galleries and Carnegie Museum of Art staff and members, doing at-home research, and even taking classes. “It’s still never too late,” Karl insists. “Do not be intimidated by it. Give art a chance.”

Their collection boasts a wide variety of media including paintings, glass, sculpture, photography and works on paper. While they have a clear aesthetic preference for abstraction and American artists, Karl and Jennifer explain it is purely coincidental. The one consistent thread that does tie it all together is the personal and emotional relationship to each as they do not buy anything they do not actually like looking at. This is clear in the display at their house as potentially intimidating works hang familiarly above plush couches and televisions. To them, the concept is simple: “We bought what we liked and found places to display.”

What does it mean then for a collection with such an intimate existence to transition to a museum and hang on the walls of a 122-year-old institution? While the context and art-historical relationship can be studied and explained, it is the stories of discovery and development unique to the Salatkas that merits being captured. Last December, amidst seasonal decoration and cheer, I sat down with both Karl and Jennifer. While Karl takes on the more outspoken role, the collection comes from a partnership with both discussing the work together and sharing it in the comforts of their home. Sitting alongside artworks by Bruce Conner, Frank Stella, Stephan Balkenhol, and Thaddeus Mosley, the three of us spoke about how the Salatkas began their collection, what it means to them, and their hopes and intentions for their generous donation to the museum.

Hannah Turpin: How long have you been collecting, and what sparked your interest in buying art?

Karl Salatka: I began collecting when I started my medical practice in the late ‘70s, buying art from local galleries that probably no longer exist, buying multiples, and without much knowledge—buying what I liked. But as far as collecting some of the more major works, that began around 1990. By then, I had established a relationship with Sam Berkovitz at Concept Art Gallery. Then later on with Richard Armstrong, who had some input as I became more involved with the museum as a Fellow. Richard suggested some of the pieces that he thought were good, like the Joe Zucker and the Al Held works, of course. It became somewhat of a triumvirate on certain pieces.

HT: How did bringing in other voices affect your collecting?

KS: That guidance was valuable, transitioning from buying locally and not having an informed mind. (I fully admit that I had zero art history knowledge prior to this time.) I was buying what I liked and what appealed to my eye, and then Sam and Richard imparted some art historical value to it, and a level of artistic accomplishment to it, where a piece fit in the oeuvre of any given artist. My spending level didn’t allow me to buy the major works, but I always felt that I could buy a work that was still representative and worthy of the artist. Affordability at all times had to be an underlying consideration.

HT: What kind of advice have you received from your fellow collectors about collecting that helped you? Has that been an influence on you?

KS: Yes. I think when we did house visitations as part of the museum Fellows Program, that helped a lot because you got to see what other collectors had in their homes. It was helpful to learn about a particular piece and be able to ask why they acquired it and if they knew of any other work on that level. I like seeing someone’s collection and having enough time to talk and say, “You know, I really like that. Tell me a little bit about it.” Collectors are always happy to share their thoughts.

HT: Do you and Jennifer talk together? Are you each drawn to certain artworks?

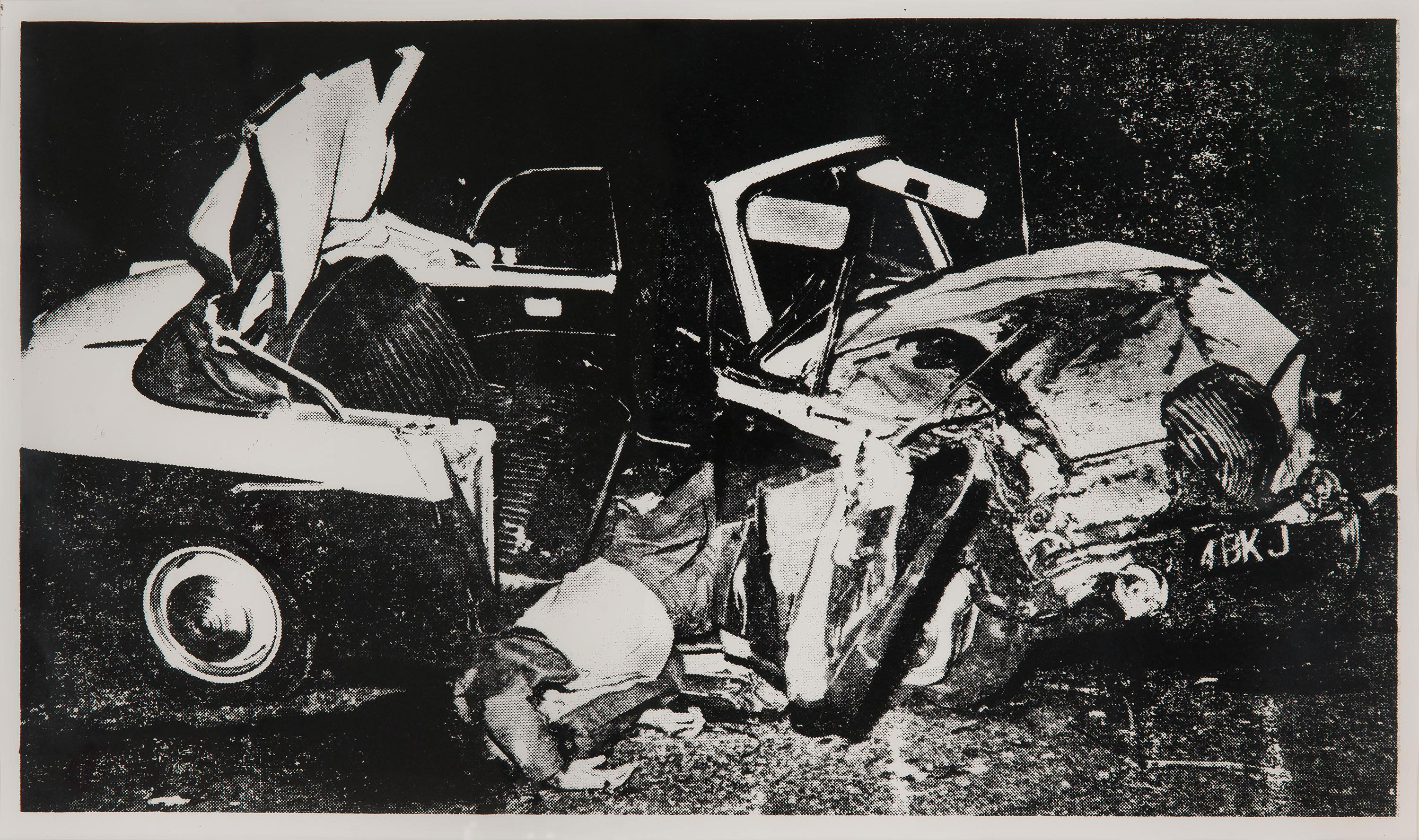

KS: Generally, I’ll show Jennifer things and luckily, she agrees with almost everything I purchase. There’s never been a conflict as to what to buy. I think she’ll tell you the only piece she really didn’t like, which the museum is now taking, is the Death and Disaster series piece by Warhol, only because she thinks it’s depressing. I think she’s now happy that it’s out of our house.

Jennifer Salatka: I also never wanted the Electric Chair.

KS: That’s the one that got away.

HT: Was art a big part of each of your lives, or your lives together before you started collecting?

Karl and Jennifer Salatka: No.

HT: How were you engaged with art?

KS: Not at all. I think that I had zero, and I really mean zero, art appreciation or knowledge prior to starting to collect. As you know, I pursued a scientific education, and I have to laugh because now that I’m retired, I’m going to Penn State here in New Kensington, taking liberal arts classes that I’ve never had the opportunity to take. When you’re a pre-med student, you’re focused on science. I was a double major in biochemistry and chemistry, and a minor in mathematics. I was so focused on that track that I didn’t have any real exposure to art, or for that matter, the humanities. I think I just started to collect some of the things that I made my mistakes on, and then started going to museums and seeing art. Even now, I kid with people on the museum board staff about my lack of knowledge. Jennifer and I don’t travel much, so therefore we rarely see other museums, which in my eyes makes us totally uninformed, I would think, compared to some. But you know what you like. In our case, collecting became more of an emotional endeavor.

HT: Do you remember the first work that you bought in the ‘90s after becoming more aware of art collecting?

KS: Richard Diebenkorn’s Berkeley (1956).

HT: What was it about that work that made you think, “This is the one”?

KS: I’ve always liked Diebenkorn’s work, especially his evolution as he moved from location to location. I also like the fact that he was going back and forth between figuration and abstraction. I don’t know, I guess the fact that it represents the landscape in a very abstracted view with his signature calligraphic marks, and its energy.

HT: I have noticed that a lot of your works are more nonfigurative, a bit more abstract. Is that personal preference? Is that more strategic? Or is it just coincidence that that happened?

KS: Not strategic, I’d say it’s coincidence more than anything. I certainly like figural works, but I think I get more energy out of abstract works. I feel they impart more energy and require more thought personally than the figural pieces.

HT: Can you describe a little bit more what you feel, what that means, what kind of energy?

KS: That’s a good question because the energy is purely emotive. In our collection, you look at Hans Hofmann, who’s almost geometric at times as an abstractionist, to Franz Kline (like the great Siegfried piece you have at the museum), who seems more structurally pared down. It’s big brush strokes and it just moves you. If you know a lot about the history of any particular artist’s work, and how referential it is to art history, sometimes that detracts from the emotive frisson of the picture. I’m stuck in the ‘50s and ‘60s, abstract, and Pop, also minimalist work, because there’s not a lot of basic knowledge of art history that’s necessary to appreciate the emotive, visual quality of this period. When you look at some of the contemporary artists now, if you take a Jeff Koons or similar artist, they are making more of a comment on art history, and a lot of present artists are. If you look at a contemporary artist like Mike Kelley and say, “I don’t get it,” well, you don’t get it because you don’t understand the reference to history or society of the time. Whereas, if you look at an abstract piece, you can simply emotionally get it. If you don’t get it, then I’m not going to try to sell you on it. With abstract art, or with minimalist art, you either like it or you don’t like it, and that’s a purely emotional thing. I don’t think necessarily they were making a lot of comment. They were reacting to, but they weren’t necessarily commenting on something that had preceded them. That’s why I like abstraction. It hits you in the chest.

HT: There is actually one work in thinking about this—the emotional connection versus understanding the history and the context of a work—your gift to us, the Anselm Kiefer. He’s an artist who’s credited with really helping to redefine specifically, German painting post-World War II, and a lot of his work is often politically charged. So how did you come across that piece?

KS: My German painters.

HT: Right, because then you have two Gerhard Richter paintings as well.

KS: The Richters and the Kiefer are great responses to the Second World War, especially Kiefer. Did I understand him before I bought him? I think so. I understood his fixation with the German people as well as German mythology and heritage and the Nazi permutation of that. It’s an emotive piece to me.

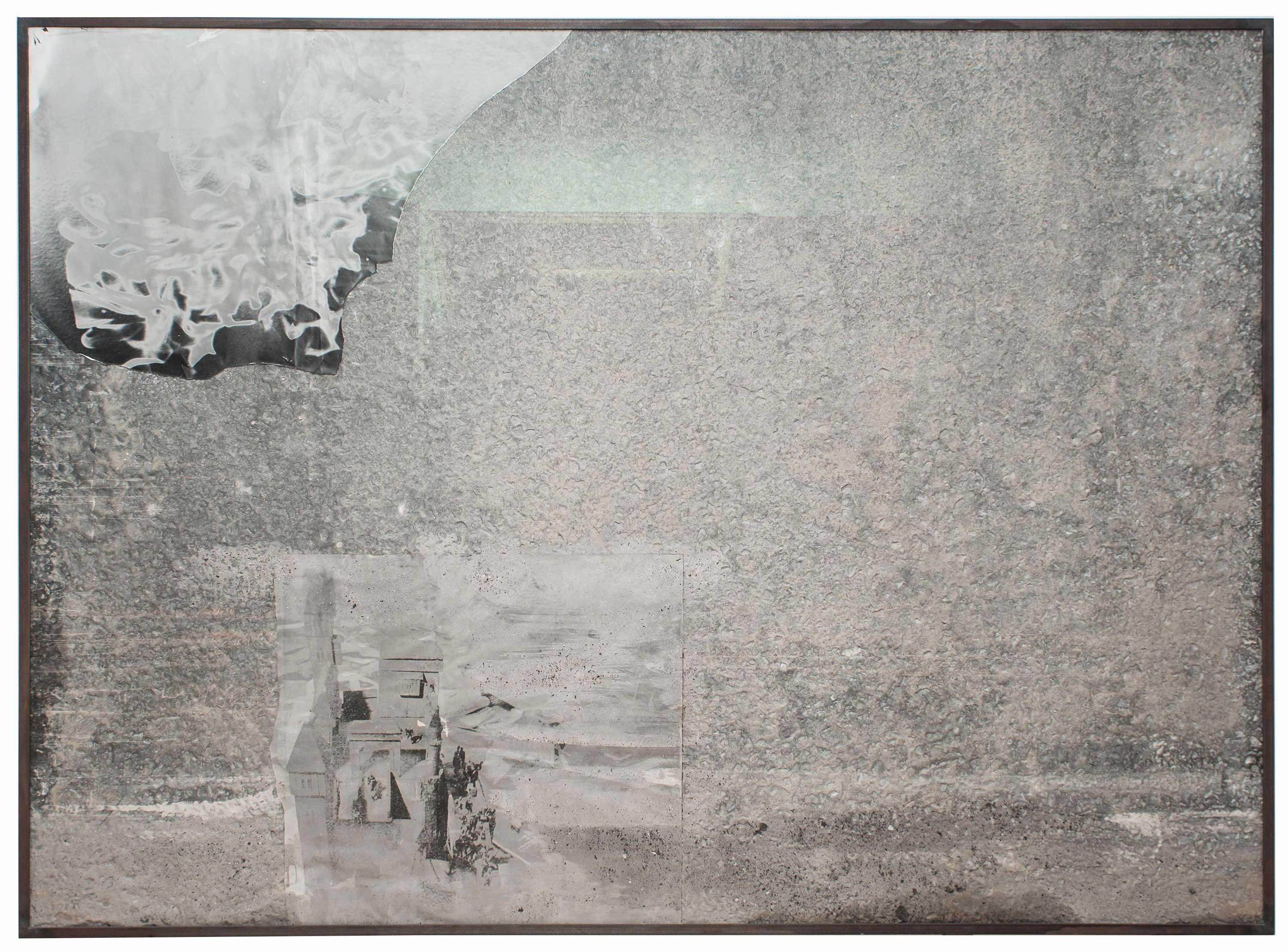

The Richter, Untitled (1969), by the same token, engages your understanding as to what he was communicating. The grays he used on that particular painting and the underpainting refers to a series where he responded to postwar buildings on a Communist block from a three-quarter aerial view, and then painted in the same grays. (And you can see a little bit of an image there in this painting.) If you closely look there you may see an image of a building as in a fog; and then he did a De Kooning-esque splatter on it. (Possibly referential.)

I think he was commenting on abstract expressionism as well as the postwar aesthetic in Europe. Europe and America were going different ways. Europe was crushed and there was depression and difficulty surviving, let alone in getting materials, while America was essentially untouched by the war. And you have the postwar feeling of American greatness in the ‘50s before we hit the ‘60s, so you have these artists with super expressive paintings—the unfettered spirits. So there’s a difference between European paintings of that time and American paintings, related but different.

I’ve always liked Richter for the same reason I like Diebenkorn. He’d go back and forth between meaningful figurative painting and then abstraction. He wasn’t fixed in any period of time. He could go back and forth and be great at both forms. A lot of artists get set on one track and that’s the end of it and it gets repetitive. But Diebenkorn is always interesting to me.

HT: You also have two very different works from Andy Warhol’s oeuvre; one where he’s trying to mimic this abstract painting that’s happening postwar and then also the print of the car crash. I’m just curious about your feelings on Warhol.

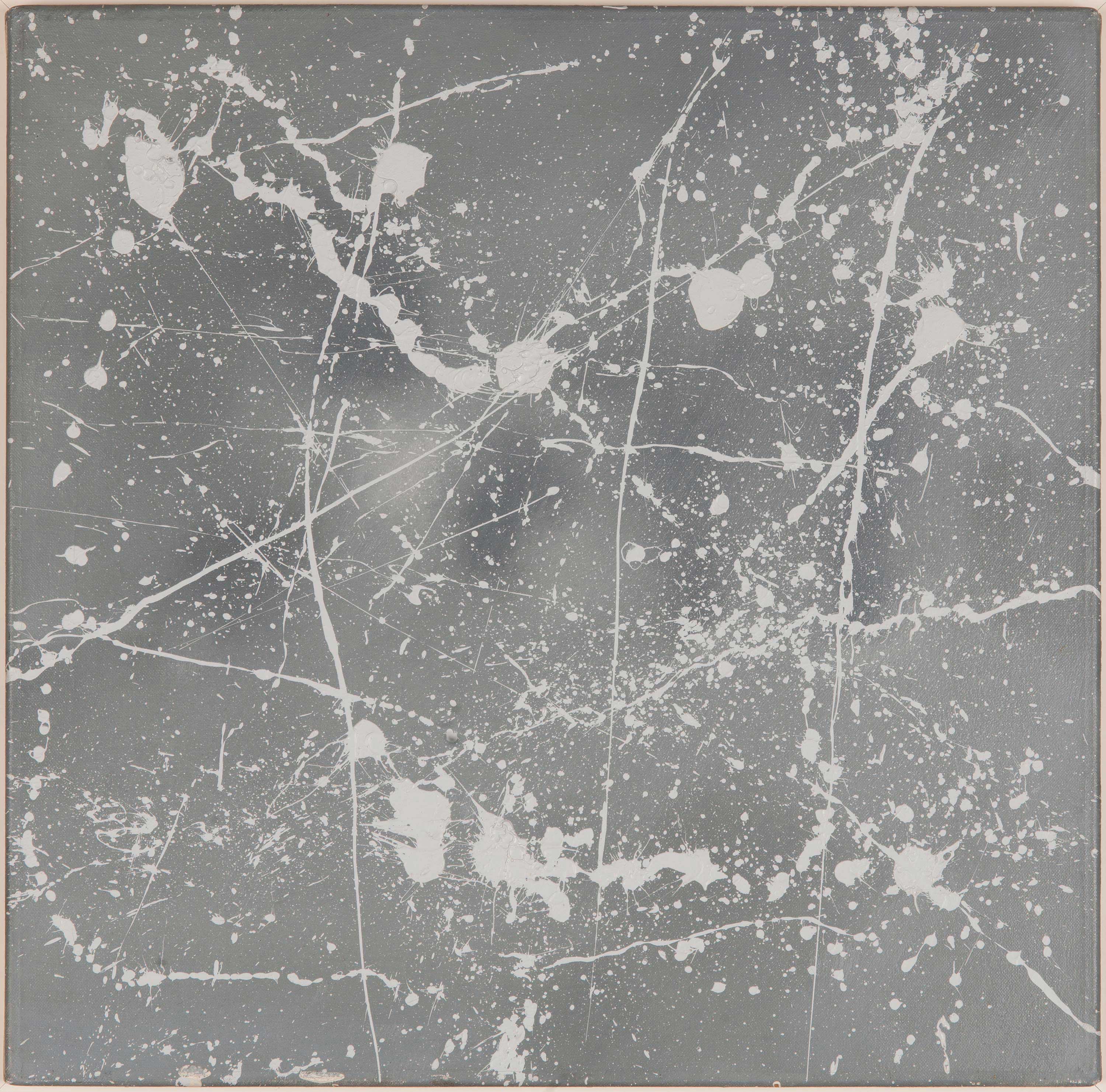

KS: I bought Warhol because I like angst, so the first piece I bought was Car Crash. Then I bought the Shadows painting. At the opening of The Andy Warhol Museum, they had that whole room of Shadows paintings. It was beautiful, and that particular one came from his nephew.

Everything was tongue-in-cheek with Warhol, I think. His foray into abstraction was repetitive abstraction, with the several different Shadows paintings he’s done and the different media—diamond dust, etc. But the Death and Disaster series paintings are my favorite, just because it’s an emotional thing to me. You can look at the painting of the botulism contaminated can or the car crash (of which there are different ones), or the suicide series. Those pieces are troubling and emotional. Guess that’s why I like them.

HT: Do you have any advice for collectors getting started?

KS: My best advice is get with the museum. Get good advice from the curators. Get good advice from reputable gallerists. Let them help you and hopefully support them.

HT: What do you feel is the role of a museum? You’re very involved with Carnegie Museum of Art, so how do you feel the museum plays a part in the community?

KS: I grew up not too far from Pittsburgh, but we hardly ever went to the museum. We didn’t grow up in families that had any interest in art. I hope that the museum, through its outreach, gets people more interested in art when they’re younger, and that interest will be continued throughout their life. I’m happy and honored that our collection is being shown because it’s something fresh that a lot of people haven’t seen. I think the best thing the museum can do is rotate their exhibitions more, even if it’s one gallery. I think that fresh art excites people. If you change what you’re exhibiting enough times, people will always be interested in coming to see and learn what’s new. Art, I think, inspires a reaction emotionally and spiritually between the art and artist and the viewer. I think that’s an important part of what a museum should do to excite the viewer and inform them.

HT: How do you hope that your collection, coming to the museum, will be a part of that?

KS: What I’m interested in and why we’ve agreed to do this would be one, that it is fresh material for most people to see; and two, I hope that it helps to attract other collectors to gift to the museum works of art. I know that museums depend on capital contributions, but art often passes in a family and then moves somewhere else and the Carnegie Museum of Art never gets it. I’m hoping this stimulates everybody at every level, even our newest members. If they buy something collectible and it appreciates and they think, well, I saw that show once and it excited me and maybe at this time I’ll be able to gift art for others to enjoy. I think that in this area, if the museum can profit by anything we have given, then we’re happy to share it.

Shaping a Modern Legacy: Karl and Jennifer Salatka Collect was on view in Gallery One at Carnegie Museum of Art from March 25 to October 15, 2017.

Until 2021, Hannah Turpin was the curatorial assistant for contemporary art and photography at Carnegie Museum of Art. Recently, she curated the exhibition The Seen and The Unseen: Three Artists Visualizing the Boundary of Space and Place at Neu Kirche Contemporary Art Center. Turpin earned a bachelor’s in East Asian studies at Denison University and a master’s in art history, with a focus on modern and contemporary art, at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. Past institutional experience includes the Brooklyn Museum, Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, and Columbus Museum of Art.

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.