Art is around you before you enter our galleries!

Take a minute to browse our museum lobbies, featuring large-scale works by El Anatsui, Sol LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner, and Christopher Wool.

Take a minute to browse our museum lobbies, featuring large-scale works by El Anatsui, Sol LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner, and Christopher Wool.

As part of the 57th Carnegie International, Ghanaian artist El Anatsui created Three Angles, a monumental sculpture that clad the façade of Carnegie Museum of Art’s Edward Larrabee Barnes building. A master sculptor known for his innovative use of post-consumer materials, Anatsui created a site-specific work that responded to Pittsburgh’s distinct geography and Richard Serra’s sculpture, Carnegie, by using reflective materials, used printing plates from a local printer, and his signature metal weave of aluminum bottle caps. While the locally sourced components of the work were recycled or discarded after the closing of the International, the aluminum bottle caps that anchored his composition were sent back to his studio in Nsukka, Nigeria. Over the past three years, Anatsui reincorporated the materials into a new work of a grand scale that features the myriad ways in which the aluminum caps can transform into patterns and shapes while creating a sense of volume from an otherwise flat material.

Anatsui is known for his exceptional openness to variations in the installation of his work; he embraces and emphasizes the flexibility of his metal sculpture by encouraging drapery-like folds in the installation process, which makes the work adaptable to the surface on which it will be mounted. Most significantly, this work is made with the museum in mind, by an artist with a keen understanding of the building, its materiality, and its artworks, such as Serra’s Carnegie and Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure. An artist of distinguished honors and awards, including the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement from the 2015 Venice Biennale, Anatsui has used his work as a platform to reorient the discourse on contemporary African art by using materials that speak to Nigeria’s liquor industry, global consumerism, and waste, and the place of African nations in the larger circulation of commodities. With conceptual and aesthetic rigor, he has pushed the discipline of sculpture to lead conversations about material histories, gravity, and plasticity. This major acquisition by the museum positions Anatsui’s work among those by celebrated sculptors of historic importance and marks a significant contribution to our collection, which can proudly be described as a living archive of past Carnegie Internationals.

How do you see yourself, your body, your views, ideas, and experiences as you move within this museum? I want, I demand, I need, I insist. Andrea Geyer’s Manifest actively acknowledges and embraces the idea that a museum is made of many people: from visitors and staff to artists, we make and remake the museum every single day. The eight banners with text facing inside and outside of the museum windows cast our voices beyond constructions of past and present and the impermeability of institutions while calling each of our imaginations into a shared space.

For Carnegie Museum of Art, Geyer invites you to contemplate your own needs and desires in relation to the museum today. The artist has created an interactive broadside to create your own list of wants, needs, visions, and demands.

Manifest stems from Geyer’s research on the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s (SFMOMA) founding director Grace McCann Morley and her belief in museums as integral to civil society and civic life. Morley led this museum from 1935 to 1958, establishing gallery tours, art history courses, a public art library, an art rental gallery, the first film program at an American museum, and the TV show “Art in Your Life.” An advocate for modern art and cultural democracy. Under Morley’s direction, the museum was open until 10 p.m. As a result of these efforts, it garnered a following that was expansive and diverse in age, race, economic, and cultural backgrounds. Morley wrote in 1950, “Art is an inseparable and essential part of human life.”

Geyer took Morley’s mission to show the importance of art in every aspect of life and scripted a list of wants, needs, and demands put toward museums as an invitation to reimagine what one expects and hopes for when engaging such institutions today. Additionally, the statements in Manifest draw from writings and lectures by Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin, and Michel Foucault, as well as from those by more recent thinkers such as Wendy Brown, Jack Halberstam, Stefano Harney, and Fred Moten. Geyer also included references in response to the 2016 presidential election (which took place while Geyer was writing the original script) that called for museums to be sites of resistance and sanctuary.

Two distinct but related wall drawings by Sol LeWitt span this wall on the stairs leading to Scaife Gallery. Seen on the left, Wall Drawing #450 was commissioned for the 1985 Carnegie International. In 1986, LeWitt saw the completed work and decided to extend it with the complementary Wall Drawing #493. Working under instructions provided by the artist, several individuals created these drawings by applying washes of India ink to a primed wall surface. Over time, the ink faded from exposure to sunlight; but in 2007, the drawings were restored to their original color and luminosity using more stable acrylic paints.

Asserting that the “idea becomes the machine that makes the art,” LeWitt was a critical figure in the shift to Conceptual art in the late 1960s. This notion, which refutes the traditional conception of the artist as exclusive author or creative genius, is underscored in LeWitt’s drawings conceived after 1970. These exist initially only as a certified set of written instructions, which are adapted to a given space by the individuals who carry out the directions (in the case of these drawings, dividing the wall “vertically into four equal parts,” and so on.) Because they conform to their particular surroundings and reflect the decisions and handiwork of the people who execute them, the works of art are different each time they are installed. Initially, LeWitt participated in the execution of his drawings, but later works have all been carried out by others who meticulously follow his directives. The 2007 restoration was completed by: Sarah Heinemann with Chantal Bernicky, Matthew Cummings, Cara Erskine, Robin Hewlett, Lilith Bailey Kroll, Dale Luce, Julia McAfee, Sandra Streiff, and Stephen Stribling.

“Walls were built for things to be put on them.”

—Lawrence Weiner

Artist Lawrence Weiner worked with language as both material and form. He believed “walls were built for things to be put on them.” For Weiner, text when installed on a wall can become a sculpture, or the description of making artwork can become the artwork itself. Acquired by the museum in 1986, Ever Widening Circles of Shattered Glass is one example of his language-based wall sculptures and does not have a prescribed location and can even be installed in more than one place at one time.

The work’s size, color, and format change based on where it is displayed. For this installation, completed months before he passed away, Weiner rendered the artwork—its scale, colors, and materials—to respond to the architecture of this space: the slope and width of the ramp, the height of the walls, and the path of museum visitors.

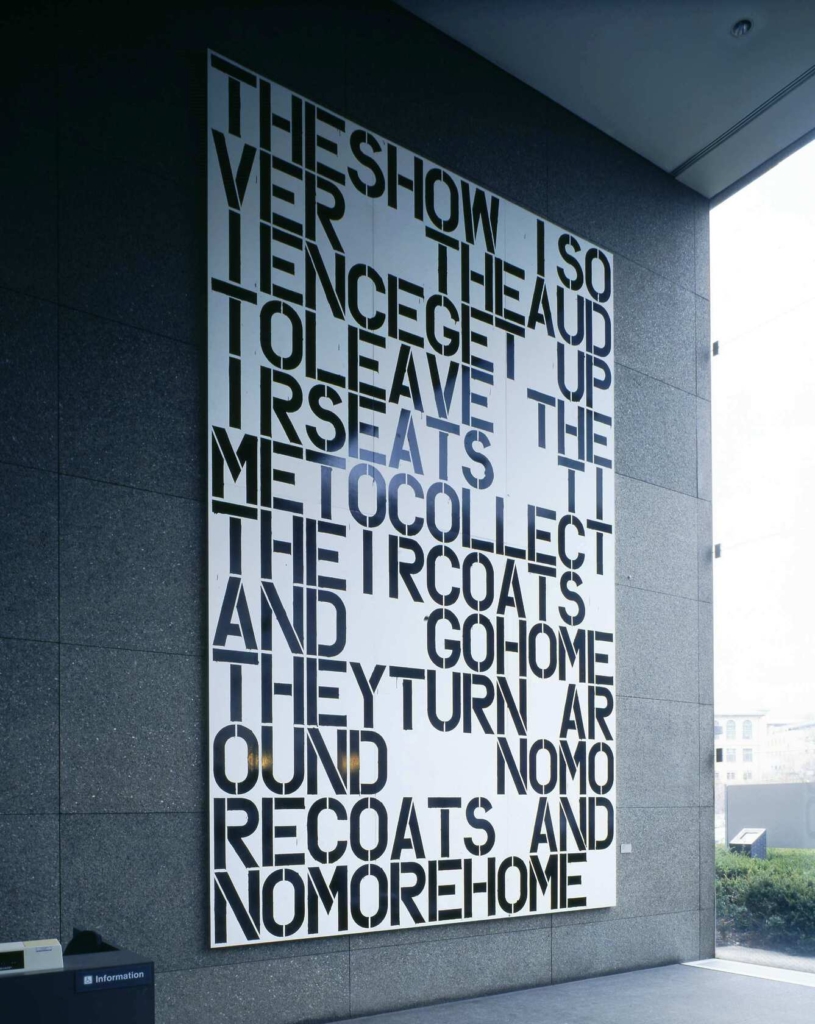

Christopher Wool made this oversize painting for the 1991 Carnegie International, where it was exhibited on an outdoor wall. Comprising an excerpt from The Revolution of Everyday Life, a 1967 book by the Situationist writer Raoul Vaneigem, it is an especially bleak assessment of contemporary rootlessness and alienation. The emphatic, geometrically spaced lettering, and the arbitrary arrangement of words recontextualize Vaneigem’s statement in an ambiguous way, imparting a sense of intrigue and foreboding to viewers entering the museum from the parking lot.

In its scale and use of text, the painting mimics the format of a billboard while calling into question the very culture of advertising. Wool developed his approach in the wake of 1970s Conceptual art strategies that questioned the conventions of painting. He often works on metal and frequently, as seen here, applies paint through non-gestural commercial processes, such as stenciling, rolling, stamping, and dripping, thus undermining the preciousness associated with marks left by a brush in the artist’s hand. Wool links his repetitive use of language to his repetitive patterns, explored through form, line, color, composition, and a particular emphasis on surface.