Architecture + Photography, featuring an array of works from the Heinz Architectural Center and Carnegie Museum of Art’s photography collection, demonstrates the wonderfully rich symbiosis between architecture and photography. The two fields have been linked since the very origins of photography in the mid-19th century. One of the earliest photographers, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, had trained as an architect, and many who experimented with photography in its first two decades used buildings as their subject matter. Photographers have continued to look to architecture—as documentary subject, evocative setting, artistic muse—in the years that followed.

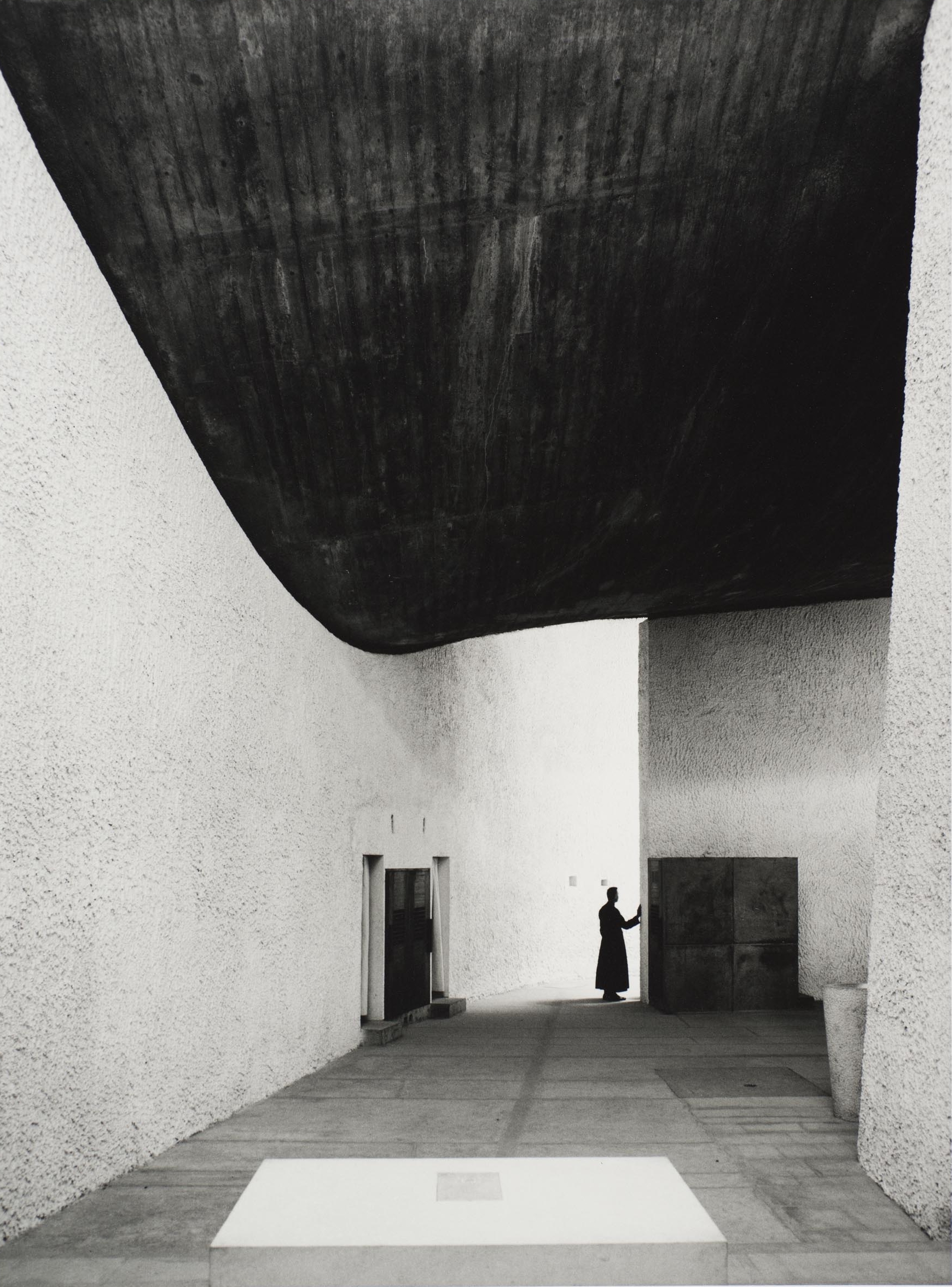

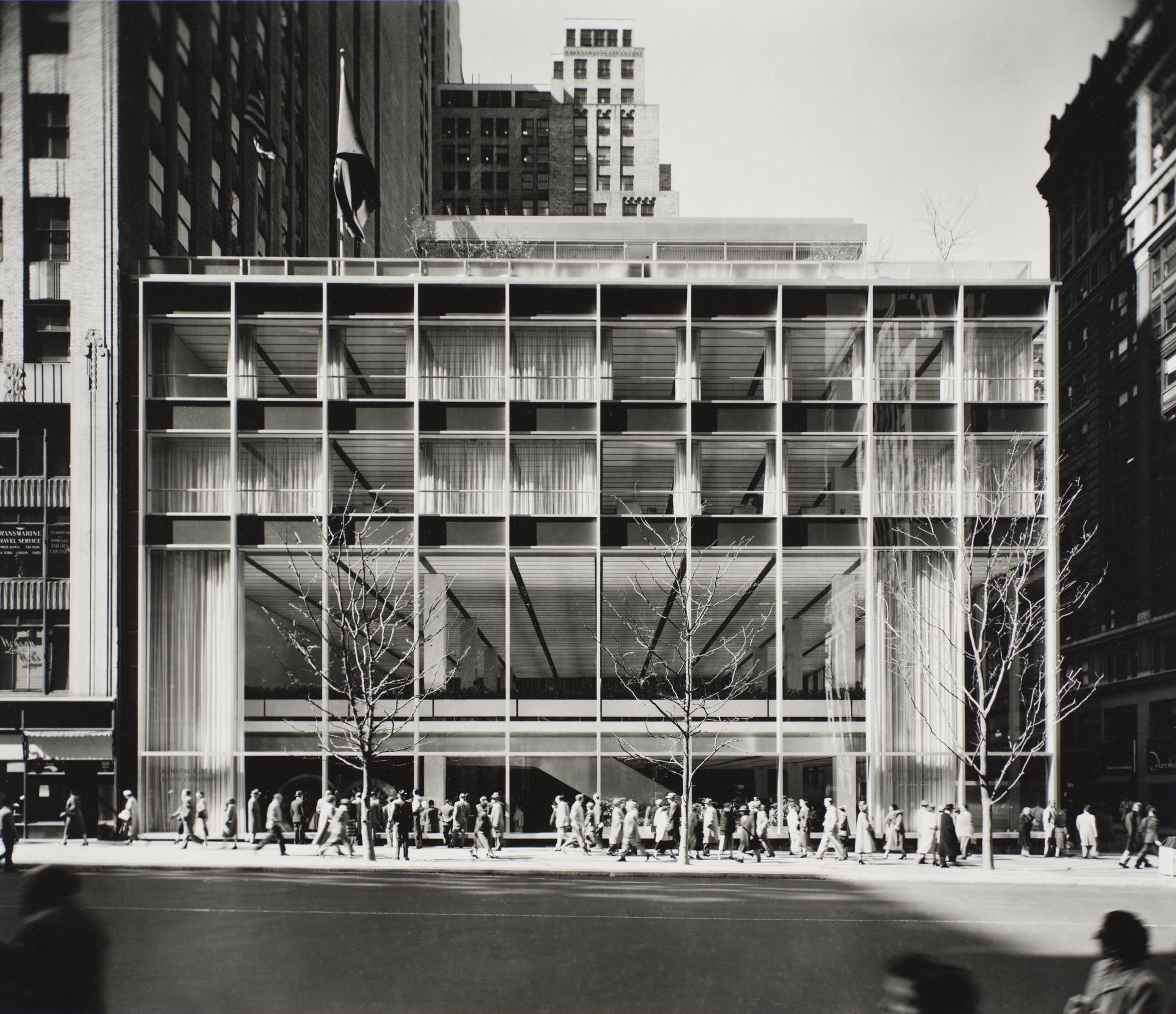

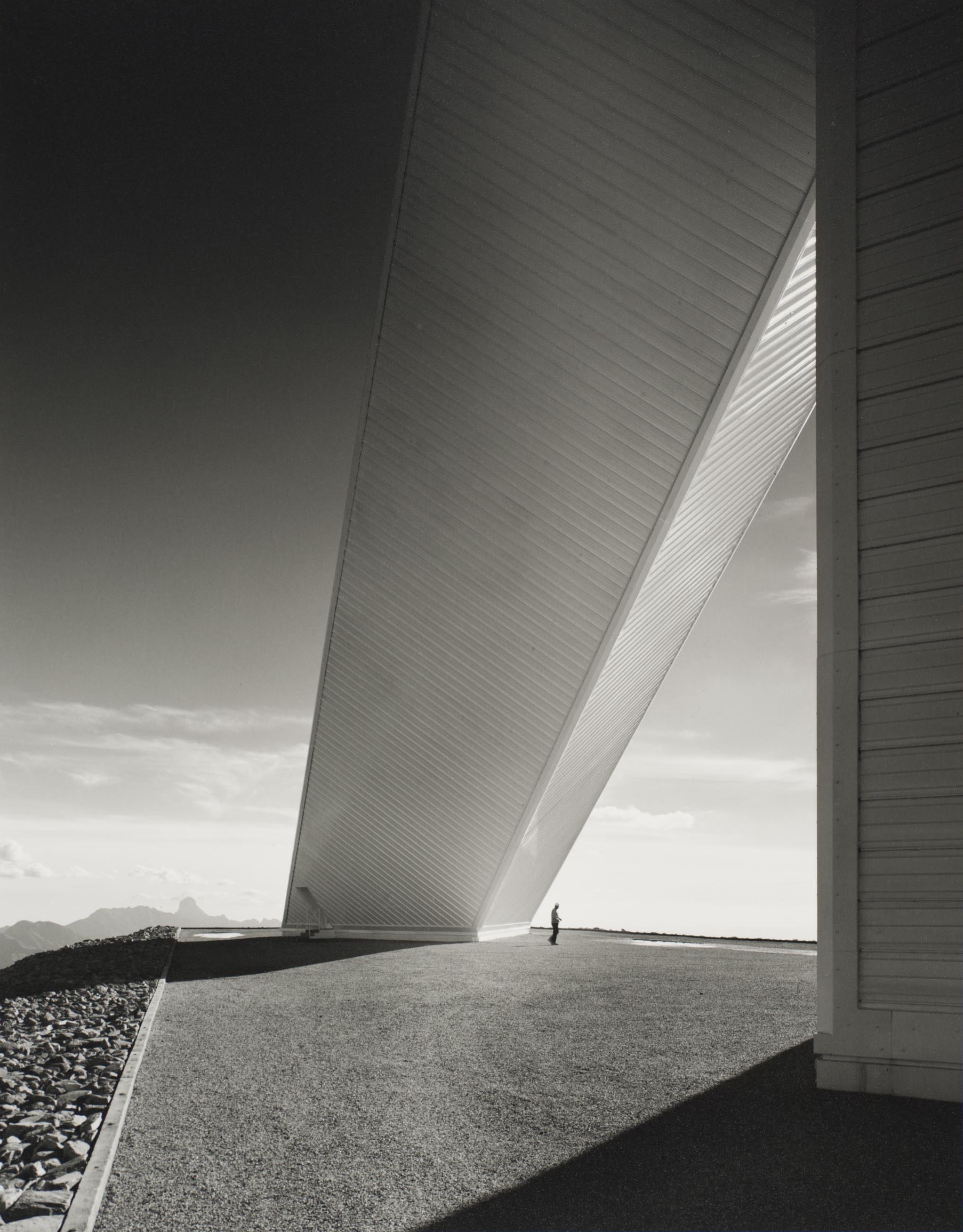

Three groups of objects in this exhibition can be considered “architectural photography”—that is, photographs primarily interested in documenting works of architecture—yet each reveals a distinct, and highly subjective, point of view. A recently acquired portfolio of iconic Modernist buildings by famed architectural photographer Ezra Stoller reveals his zeal for promoting the work of Modernist architects. A selection of photographs by Frances Benjamin Johnston of historic buildings in Charleston, SC, reflects on photography as a form of preservation of our changing built environment. And a range of images from the early 20th century of important sites and buildings from around the world reflects a desire to acquaint people with far-flung sites and monuments.

In the fourth section, a selection of images from the museum’s photography department—including works by Richard Artschwager, Dan Graham, and W. Eugene Smith—reveal how artists use architectural forms and imagery in their work to explore other ideas, whether they be narrative, compositional, or even political.

The works in Architecture + Photography provoke a variety of questions. How does a photographer’s approach to a subject affect our experience of it? Can there be such a thing as a truly objective photograph? Is it possible to tell when architecture is the subject or simply a character in the scene? Collectively, these images compel us to probe our understanding of the built world, as well as representations of it, a bit more deeply.