“the artist can only realize himself through active effort to be what he really is.” Raymond Saunders 1

The most difficult part of being an artist, beyond certain harrowing moments of the creative process, is what, Raymond Saunders describes as “periods of profound discouragement.” 2 It is a particular sense of isolation that can distract or completely upend art making and, without dipping too far into the darkness, could even endanger one’s life.

Black feminist performance artist, Gabrielle Civil addresses this concern in a performance excerpt from her book, (ghost gestures), in which she states, “The unwritten shadow book is not a failure of the writer … the unwritten book is a loss for all of us.” When I found a publisher willing to take a risk on my hybrid memoir, I felt the need to invoke Civil’s sentiment throughout my writing and revision process, to friends, among community, and loved ones, in acknowledgement that some of us may never finish our work, let alone find a home.

This darkness can be difficult to speak of, those stretches in which sleep alludes you, and very little will satiate your most audacious and conflicted inner turmoil. The fact of our race and gender afflicts this consciousness with a ruthless and unavoidable snag, convincing us that the process of naming ourselves must consider our inherited responsibility. I am an artist. Am I an artist? Some of us falter here, slinging accusations or cowering at presumed missteps.

It is a timeless quandary that is contained within the contemporary ideas of what it means to be Black in America. “What it means” involves a cyclical redefining that teeters back around every few years, often prompted by which white man is in charge and how much we have to lose. This cycle also presents a specific crossroads within our racialized context: how well do we actually know ourselves and how willing are we to perpetually explain?

Is the Black artist inevitably or obligated to be both black and artist? I have found myself firmly positioned on both sides of these considerations. As a kid in high school, I started to name myself as a writer, quite readily. The title felt clear and certain. Inarguable, even. The space in which my thoughts could sing on the page felt unabashedly mine. Couldn’t my writing be the one space where my writing could be raw and unencumbered? Looking back, I can see that this feeling stemmed from my early experience with the tension of race and gender. I was becoming a Black woman, which ultimately means, I was becoming more visible to the world. As a teen, I was deeply familiar with racism, but as a girl becoming a woman, I was quickly being exposed to a more sinister, persistently derided status.

Even as I write this, I wander what Saunders would consider my capital “B’s.” An epistemic reaction to the 2020 racial uprisings, or a forced habit for a writer who has been edited by well-meaning art publications. Either it was house style, and I needed to keep up or it wasn’t house style, and we needed to have a talk. I am an artist. Am I an artist? If this is true, then I must also believe that “Black is a color.” There is ongoingness here, despite the declarative nature of the sentence.

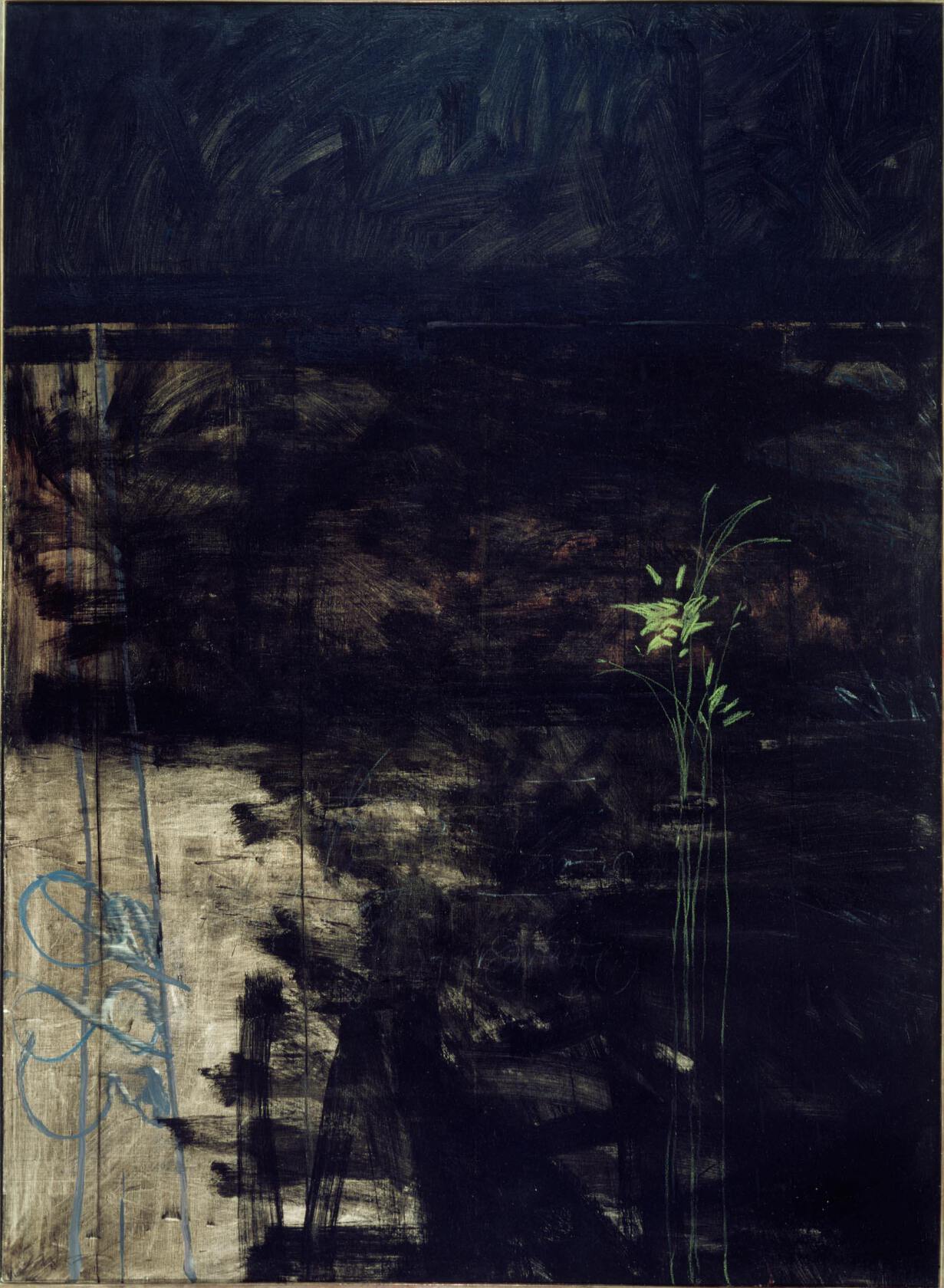

I find the most compelling part Saunders’s essay, “Black is a Color,” occurs after needling through Reed’s article. It is in the second half in which Saunders vulnerably address the “profound periods of discouragement” that artists face. “Get real” is Saunders’s tone and not only is he addressing Reed, but Saunders is also speaking to all of us. He insists that we all stop believing in a context in which amplifying our suffering will save us. Shuttling beyond poles of convincing and refusal, Saunders most often resides in the space of yearning.

“…every creative person is subject to periods of profound discouragement, when denied recognition of the vision he embodies in his work. the denial seems to constitute a rejection not only of his work but of all he is striving to be.”

It is here that Saunders illuminates a different kind of tension, perhaps beyond being Black and artist that requires our commitment to using this darkness rather than letting it define us.

“… but when anger, a human reaction, gets syphoned off into serving merely as a political expedient, it is robbed of genuine humanity, and is useless as inspiration to the artist as a man.” Raymond Saunders, Black is a Color 3

Saunders’s essay begins here, firmly positioned in opposition to Reed’s claim at the difficulties at being Black and artist. Saunders never actually disagrees with Reed’s sentiments; rather, he is bothered more by their single-minded testimony of the Black experience. He seems to desire more time questioning what brings us to make art and the vast periods when we cannot. The artist, as James Baldwin describes is, “the incorrigible disturber of the peace” and with that framing comes “peculiar nature of this responsibility is that he must never cease warring with it, for its sake and for his own.” 4 Based on this, it would be easily to assume that to name oneself an artist is much riskier than any other qualifying condition. While it is all maddeningly cyclical, there are many limitations beyond the resources we possess.

It would be hard to consider this topic of consciousness, and whether or not our consciousness is inherently abused by racist assumptions, impressions, or limitations, without also considering gender. There is no place where my race is not recognized alongside my gender. The sideways looks I get in the pharmacy, the way people retract a “Hello” once they scan the speaker. It doesn’t matter what I could wear, or what I’m not saying. Perhaps, the most irritating tension lies in the fact that often, the more my gender is acknowledged the less visible or credible or present, I become. This is not only a feeling, an emotional reality, it is the sinister feature of being named. Much of Saunders’ critique involves a sense of yearning, a desire to be seen more than the reality of the condition. Black is a color. Black is also… Black.

One of the pioneering Black women artists of abstraction, Howardena Pindell, comes to mind. Pindell’s art often examined her Black womanhood as a central inquiry. While researching my book, I had the sweet fortune of pouring over Pindell’s writings, specifically the extensive volume, The Heart of the Question: The Writings and Paintings of Howardena Pindell.

In one section, Pindell is preparing for a 1988 group show featuring women of color artist, called, Autobiography: In her Own Image, at INTAR Latin American Gallery in Manhattan. 5 Pindell invited artists to her studio to discuss the premise for the show and inspire a process of art-making that was unencumbered—an invitation for viewpoints “which may not be particularly pleasing to the dominant culture.” 6To provoke their discussion, Pindell selected prompts from a list she had previously written in her own journal. They are listed below, including the sequential numbering found in the original list:

6. The brutality of omission as appropriation.

7. Use of omission as a form of censorship: First Amendment rights for whom? 7

Pindell’s fervor introduced Black feminist consciousness to the art world, a crucial disruption to the “single-minded” affect contemporary womanhood, abstract conceptions and art world feminisms holding fastidiously to their limited scopes. The symbolism of the Black male artist and the Black woman artist involve legacies in which the phrase “Black is a color” contains a dueling emphasis. Saunders considers, “My art is about what I make as opposed to what I think about what I make.” Which introduces a deeper consideration in line with Pindell’s thematic assertion – how much of what “I think” is critical to the making? For the frightful, discouraged, tender, and outrageous Black artist, is this what is contained within our Blackness? Or might I be asking, can Black people who make art, consider their Blackness or what it means to be Black without the need to speak for all of us?

Erica N. Cardwell is the author of, Wrong is Not My Name: Notes on (Black) Art (Feminist Press, 2024) which was chosen by Electric Literature as the Best Nonfiction of 2024. She is the recipient of a 2021 Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant and a New York State Council for Arts, Grant for Artists. Her writing has appeared in ARTS.BLACK, Art in America, Frieze, BOMB, The Brooklyn Rail, C Magazine, The Kenyon Review, and other publications. Erica has written exhibition and catalogue essays for artists such as Crystal Z. Campbell, Rico Gatson, Samantha Box, Chitra Ganesh, and Sandra Brewster. She teaches creative writing and arts management at the University of Toronto Scarborough.