File on the Declaration of José Antonio Aponte and the Meaning of the Book of Paintings Seized at His House

Preface from the translator and the editor

The following text is the translation of a trial record. The trial took place in Havana in the spring of 1812 after colonial authorities discovered plans for a far-reaching revolt which aimed at ending the colonial order and the institution of slavery in Cuba. The original document, a manuscript in the handwriting of the court’s scribes, records the interrogation of the revolt’s suspected leaders, a group of free Black men who lived in Havana. Among them was José Antonio Aponte, a veteran of the free Black militia, a carpenter and a sculptor. He and others were repeatedly questioned about a remarkable object discovered during the search of Aponte’s house: a “libro de pinturas” which can be translated as “book of paintings” or “book of drawings.” The colonial authorities clearly understood Aponte’s artifact to be subversive. However, they were also confounded by the images’ representations of biblical, mythological, historical figures and events spanning ancient and modern history and connecting Africa, Europe, and the Americas. While the book has been lost, possibly destroyed by colonial authorities, echoes of this important and extraordinary work of art remain in the judicial archive. The following text is the translation of the parts of the 6,000 pages recorded by the court’s scribes that focus on several days of interrogations about Aponte’s Book of Paintings.

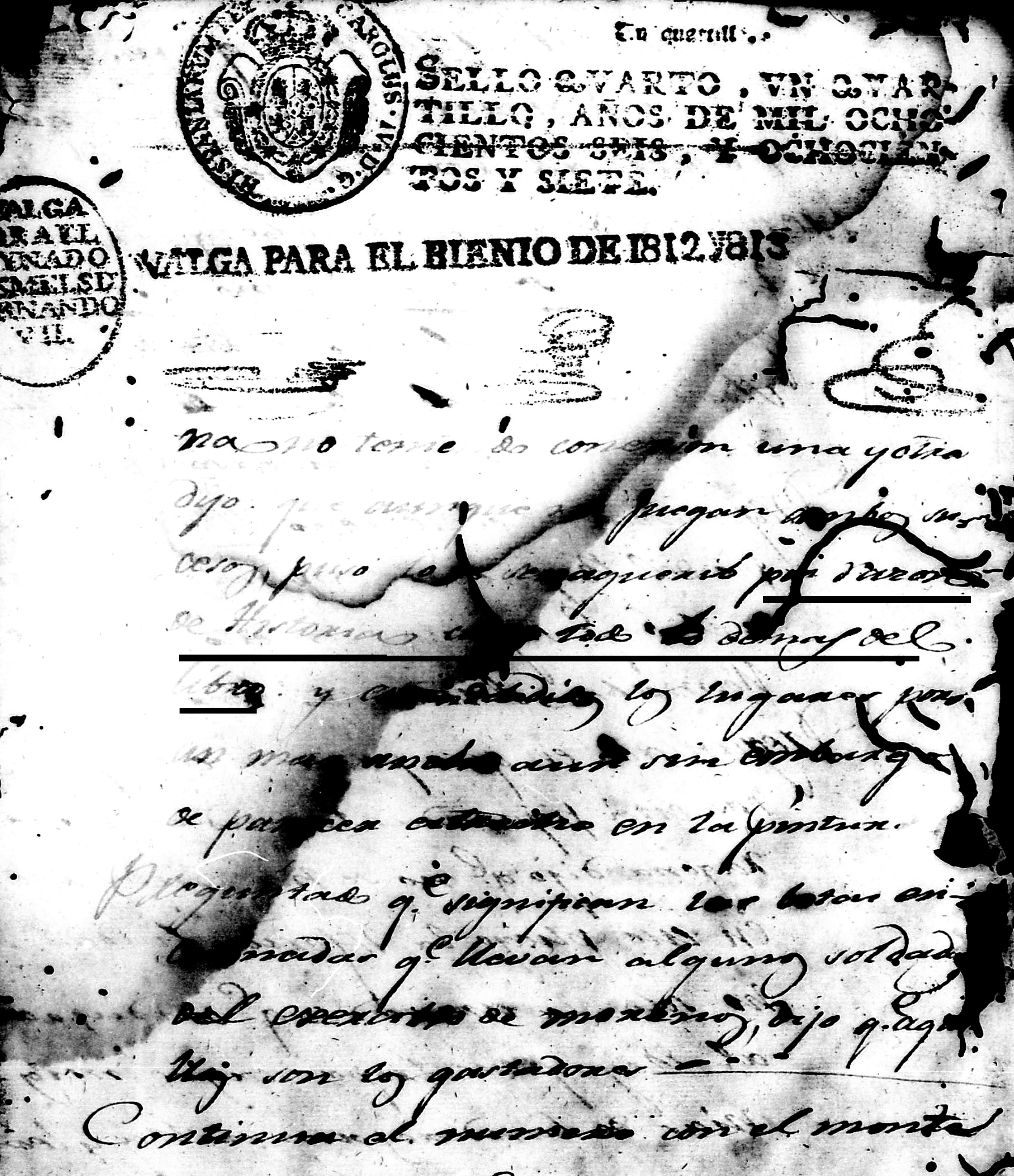

The source text used in the translation is the transcription published by Jorge Pávez Ojeda in Anales de Desclasificación. Pávez Ojeda used the following source to do the transcription: “Expediente sobre declarar. José Antonio Aponte el sentido de las pinturas que se hayan en el L. Que se le aprehendió en su casa. Conspiración de José Antonio Aponte, 24 de marzo de 1812,” which are located at the National Archives of Cuba (Archivo Nacional de Cuba, Fondo Asuntos Políticos. Legajo 12. Número 17). As with other criminal and inquisitorial records, it presents many challenges. Written by court’s scribes, the text is without standardized spelling. It includes very little punctuation, creating running sentences and ambiguous syntax, and making the meaning at times very difficult to ascertain. We have decided to adhere to the sentence structure when possible. However, we also decided to follow contemporary English uses of upper- and lower-case letters and added punctuation in the interest of clarity, knowing that such additions at times necessarily construct an interpretation of the source text. Pávez Ojeda’s transcription includes numbers in bracket that refer to pages in the original manuscript. These have been retained in the translation. We also decided to retain the judicial language used in the manuscript. These include the full Spanish titles given to colonial officials as well as the use of phrasing like “the declarant” or “the one who answers” to refer to a person making a statement during questioning. Additionally, the source text abounds in brackets with either full or broken words. When the broken words in Spanish cannot be translated, we decided to indicate the presence of the untranslatable passages with the use of […], to emphasize the incomplete nature of the transcript and the consequent difficulty or impossibility of translating some passages. When we added words to clarify a sentence or identify an individual or object referred to, we used brackets. Additionally, the translator had to research the Spanish colonial meaning of specific words which are recurring in the source text. One of them, cédulas, which is translated here as decree, historically referred to official written documents, often issued by the Spanish Crown or colonial authorities, and which were used for various administrative, legal, or bureaucratic purposes. Another word that required some thought was países, which could be used in reference to landscapes or views more generally when discussing images or artworks, especially in the context of colonial paintings or illustrations. Another word that required some digging was platilla, the material of several rods about which Aponte and others are repeatedly interrogated. This material was a lesser quality silver used for various purposes, but it was not necessarily “cheap” in the contemporary sense. Rather, it was a lower-grade silver compared to the larger and more valuable pieces like plata (standard silver). The term often referred to is fractional silver—smaller silver pieces or coins, which were used for routine, everyday transactions, or as smaller units of currency in the colonial economy. Here it is translated as “raw silver,” to retain the sense of its unrefined or lower grade quality. Another word laminas identifies specific passages in Aponte’s book of paintings. From the trial record, it appears that Aponte organized his work in sections, which he identified with the term laminas and a number. Some of these included more than one sheet of paper. Rather than its direct translation “sheets,” we have preferred to use the word “folio.” A folio is one or more sheets of papers folded once and sewn together, each sheet making four pages in a book. This term evokes a possible approach Aponte used for making and organizing the material sections in his work, while retaining some degree of uncertainty. Additionally, when we could not ascertain the meaning of a word, we kept the original word, italicized in the translation.

Finally. the source text includes many terms to identify different racial designation reflecting not only the ethnic diversity of early 19th-century Havana, but also the Spanish colonial racial classification system. The term negro is translated as Black. However, the source text also uses another term to describe Aponte on several occasions: moreno, which has also been translated as Black. A third term, mulato, historically referred to people of mixed European and African ancestry, is also used in the trial transcript. Because of the offensive nature of its literal translation to English, the preferred translation is Brown. Pardo is another word used for ethnic categorization that referred to people who were of African and Indigenous heritage or to people who were of African and European descent. It is translated as well as Brown. A fifth term, indio, has been translated as Indigenous. Finally, the text also mentions the term moro (Moor), a word used to refer to people of Muslim faith. It has been translated as Muslim.

It is important to remember that the testimonies recorded in the manuscript were obtained under duress and likely torture, but that the conditions in which the information was obtained is not part of the trial record. Aponte and the other individuals interrogated about the “Book of Paintings” knew they risked their lives with any information or explanation they told the colonial authorities. The translator and the editor relied on several scholarly sources, including Digital Aponte, a website hosted by New York University, and which made Pávez Ojeda’s transcription available online, with abundant commentaries. Aponte’s rebellion and his book of paintings have been the topic of extensive scholarly research. Additional sources are listed in the bibliography below.

Alba Campo Rosillo, PhD, translator

Marie-Stéphanie Delamaire, editor and curator