A Note to the Reader

“Keramik zwischen Malerei und Skulptur” (“Ceramics between Painting and Sculpture”) originally appeared in Kuhn – Ceramics, 1953 to 1989, published for the exhibition at the Museum for Kunsthandwerk, Frankfurt am Main. It was based on conversations between Dr. Sabine Runde and Beate Kuhn. Although assiduously footnoted by Dr. Runde, this oral history reflects its subject’s memories and point of view. Not every detail could be confirmed. In 2024, Carnegie Museum of Art commissioned a translation of the following excerpt for the benefit of English-speaking audiences.

Carnegie Museum of Art thanks the Museum Angewandte Kunst in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, for permission to publish and Dr. Sabine Runde for revising her research for the contemporary American reader.

—Rachel Delphia, Alan G. and Jane A. Lehman Curator of Decorative Arts and Design

Ceramics Between Painting and Sculpture

For Beate Kuhn’s generation, which grew up during the Nazi era, an uncensored world first opened up after the end of World War II. A spirit of dynamic optimism grew in contrast to the intellectual isolation of the restrictive, authoritarian Germany of the 1930s and 1940s. The young people encountered everything new with great openness and enthusiasm and discovered long suppressed intellectual and artistic developments.

They determined to acknowledge the example of art made by the artists who had been persecuted and forced to flee to safe countries because the fascist National Socialist regime had classified their work as “degenerate.” This art became the departure point and the standard for young German generations to follow in resolving their own visions.1

After qualifying to enter university in 1946, Beate Kuhn allowed external circumstances to dissuade her from her first choice of career (her original wish had been to start a ceramics training course with German ceramicist Richard Bampi (1896–1965)).2 Brought up by artistically inclined parents (Erich Kuhn and Lisa Kuhn-Zoll), Kuhn began studies in Art History in Freiburg (1947–1949) with a certain indecisiveness. Although she was familiar with artistic work—her father’s occupation as a sculptor3 and his library of art books offered rich visual material—she found herself confronted with a plethora of new impressions.

In that era, Freiburg University offered a series of supplementary lectures to any takers from all disciplines—a tradition for studium generale.4 Like all students after years lacking in stimulation, Kuhn took up this offer with great interest and followed lectures on philosophy and psychology, apologetics and theology, as well as history.

Although still banned from teaching, the philosopher Martin Heidegger (German, 1889–1976) was sometimes present, and often took the floor, during various events held by his friend and art historian Kurt Bauch (German, 1897–1975). Students could also read avant-garde literature and formerly banned authors. Everyone could find out about new literature in the Quakerbaracke, where meals for students were provided by American Quakers as part of a postwar relief effort for civilians.

Art History under Kurt Bauch and Elisabeth (Lisa) Schürenberg (German, 1897–1975) offered not only seminars and lectures on classical subjects, such as Painting of the Middle Ages, Late-Gothic Sculpture and Architecture in Germany, or Italian Renaissance Architecture, but also on contemporary subjects. In the summer semester of 1948, Bauch held his legendary lecture on 20th-century art5 and was thus one of the first who compiled a summary of the developments in painting and sculpture of the previous 50 years.6

The Art History Institute, as it was called, was small (about 20 students, unthinkable today) and was housed in the former Augustine monastery together with the Augustine Museum and its collection.7 Bauch’s lecture subject was highly topical, and his talk was rich with intellectual stimulation enhanced by direct encounters with original works of art.

In such small groups, the students profited enormously from the direct exchange with the influential teacher. Bauch knew how to open their eyes to the uniqueness of the artworks. He travelled with his students to various exhibitions, which showed works once inaccessible to the public or that had been put into storage during the war. For instance, in connection with a visit to the workshop of abstract painter Otto Ritschl (German, 1885–1976), they were able to see the exhibition of Prussian Cultural Heritage, brought to Wiesbaden for the first time (young people had missed out on cultural history in general because travel and access were so curtailed during the war). They also saw the large exhibition Art of the Early Middle Ages in 1949 at the Art Museum of Bern, Switzerland, from which Kuhn took lasting memories of the manuscripts. It was not far to Basel, and to the Museum of Art, with its collection of modern painting and sculpture. Here, Kuhn made her first acquaintance with works by Paul Klee (Swiss, 1879–1940), to whom an exhibition was dedicated later in Freiburg.8 Apart from Klee, Kuhn saw smaller exhibitions of the paintings of Erich Heckel (German, 1883–1970), Otto Dix (German, 1891–1969), and Ferdinand Macketanz (German, 1902–1970), among others.9

During that postwar period, Germany was divided into zones under the administration of the Allies. As Freiburg was situated in the French zone, works of the French Modernists10 were exhibited. In 1947, Maurice Jardot,11 at that time staff member of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler,12 made possible the exhibition Meister französischer Malerei der Gegenwart,13 with works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Fernand Léger, and Georges Braque among others (fig. 1). After viewing the exhibition, the students discussed the avant-garde French painting quite controversially, the exhibition itself was quite controversial as noted in the catalogue of the Braque exhibition, which followed in October 1948. Beate Kuhn specially mentioned that also Willi Baumeister (German, 1889–1955), one of the most important artists and teachers of that time, traveled to this exhibition with his students from Stuttgart.14 In the same year, there was an exhibition of color etchings and lithographs from André Beaudin, Marc Chagall, Raoul Dufy, Juan Gris, and Henri Laurens, among other artists.15

This inspiring intellectual life in Freiburg, and the diverse directions of the artistic statements Kuhn absorbed firsthand, strengthened her wish to realize her own artistic, expressive urges. In addition to her studies, Kuhn made committed attempts16 at linocuts, watercolor, and tempera, which, instead of giving her satisfaction, intensified her restlessness. In this way, she firmed up her decision to begin formal artistic training.

For economic reasons, it was also appropriate to move to her parents’ home in Wiesbaden and to register at the School of Applied Arts (Werkkunstschule) where her father taught. However, despite her father being a sculptor, she did not begin in the sculpture class, instead deciding on ceramics, her first choice of career.

The Werkkunstschule of that time was technically poorly equipped, making possible only a limited craft practice, which, in retrospect, Kuhn saw as purely training in turning on the wheel. Her sense of proportion was sharpened through methodically building a container series, with the aim of shifting the center of gravity. On top of that, through her teachers Erika Opitz and Hans Karl Starke, who, as students of Bauhaus master potter Otto Lindig (German, 1895–1966) taught in the Bauhaus tradition, she received a significant formal education (fig. 2).17

Because of the lack of kiln firing possibilities at the Werkkunstschule, the ceramicist Paul Dresler (1879–1950), who was already over 70 years of age, was not able to ignite the students’ spirits for glazing despite his rich experience. After two years, Kuhn finished the apprenticeship, qualifying as a journeyman.

As a continuation and expansion of ceramic training, she chose the Werkkunstschule in Darmstadt, which offered the best conditions for an intensive further study through an outstanding technical setup and a wide choice of specialist literature and journals (1951–1953). Under the leadership of Friedrich Theodor Schroeder and later Margarete Schott (German, 1911–2004), Kuhn acquired all the other techniques in addition to turning on the wheel. She gained experience through experimentation with various clay compositions prepared in a mixing mill,17and with the aid of drum mills18 in the laboratory, she systematically built up her knowledge of glazes.

The period in Freiburg, Wiesbaden, and Darmstadt, as well as the subsequent years in her first workshop in Lottstetten (1953–1956), were marked by seeing, traveling, and absorbing. Kuhn still traveled because of cultural events and went to Freiburg to see a Richard Bampi exhibition at the Augustine Museum. At the Kranichstein Music Festival, she heard one of the first concerts given in Germany by Austrian composer Ernest Toch (1887–1964) after his return from the United States, as well as works by other younger composers, such as Dieter Schnebel (German, 1930–2018) and Hans Werner Henze (German, 1926–2012). She experienced music synesthetically (she spoke of color and spatial experiences). Throughout her life, new music remained a meaningful source of inspiration in her own work.

Kuhn connected diverse and long-lasting impressions with an excursion to the International Conference of Craftsmen in Pottery and Textiles in Totnes, Devon, England, together with her teacher from Darmstadt, Schroeder, and the Applied Art students, in 1952.19 There, she saw English sculptor Henry Moore’s large reclining figure in the park landscape of Dartington Hall for the first time (fig. 3).

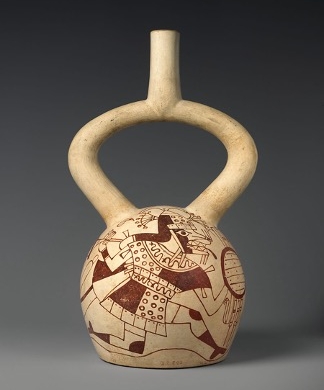

The journey, which was on bicycles, went via Paris, where Peruvian ceramics were a new discovery for Kuhn (see fig. 4). The tension of the contours and the refined forms impressed her deeply, appearing to influence her both intellectually and emotionally. Here, the formal language of the archaic revealed itself in its perfection to her once again, as it had impressed her earlier in ethnographic books20 and through the objects her father brought back from a trip to India. Achieving such quality in her own work became a major goal for her.

The international conference in Totnes was a unique opportunity for the students to become acquainted with the international tendencies in this field of art. Ceramicists from Spain, France, Italy, and Holland, from the US, Canada, Mexico, and Australia, introduced their work and represented their countries. Others passed on their working methods on the wheel, such as Shōji Hamada (1894–1978) from Japan, whose irregular vessels mirrored his whole experience and the rich tradition of his country, which, despite their early skepticism, later impressed the students.21

In an article, Kuhn reviewed the English international exhibition in which different countries were represented during the conference.22 The essay provided information about the technical and artistic goals of the various artists and testified to the author’s excellent knowledge of the international ceramic scene.

Also during this period, Kuhn undertook trips to nearby Switzerland. Exhibitions of sculptures by Henry Moore,23 watercolors by Henri Laurens,24 and sculptures by Julio González (Spanish, 1876–1942)25 attracted her strongly. The worldliness and continuity of Switzerland was evidenced by the collection of modern art at the Basel Art Museum. The valuable collection of non-European art at the Museum Rietberg, in Zurich, revealed additional enlightenment. In 1955, Beate Kuhn embarked on an extended journey through France together with friends, the ceramicist Karl Scheid (German, 1929–2019) and wood sculptor Bernhard Vogler (German, born 1930). They visited Le Corbusier’s house in Marseilles and Picasso’s ceramics26 in the Musée Picasso in Antibes27, flooded with light. The friends also did not miss the big Picasso retrospective, 1900–1955, in the Haus der Kunst in Munich. In a gallery in Düsseldorf28 in 1957, Kuhn also encountered sculptures by Marino Marini (Italian, 1901–1980). She already owned a small monograph29 about him, as well as González and Laurens, published in 1954.

From today’s point of view, each of these activities involved inconvenience, because they mostly traveled by bicycle or, as from 1955, in a small Lloyd vehicle. However, despite experiencing closed borders and other obstructions, Beate Kuhn and her generation never considered it to be difficult. The crucial factor was the attraction of modern art and the passionate interest in painting and sculpture, as well as in music and ceramics.

The Female Figure

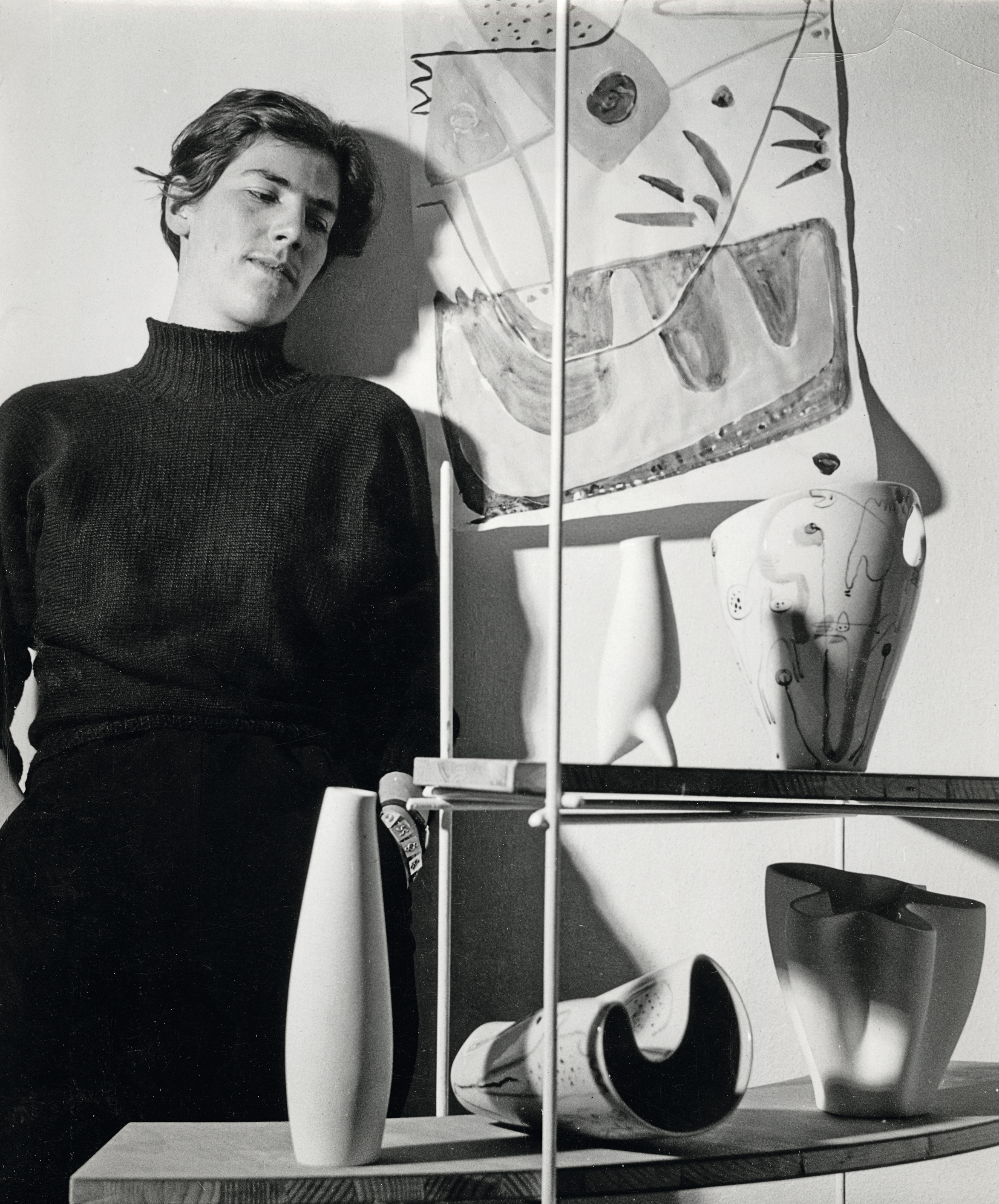

The years in Wiesbaden (1949–1951) were a time of artistic introversion for Beate Kuhn. The diverse impressions from Freiburg seemed to slumber, and—to the disappointment of her father—her urge to make pictorial statements was not reflected in her work. Finally, in Darmstadt, through experimental developments in new directions according to her own ideas, Kuhn developed her first forms based on the wheel-throwing skills she acquired in Wiesbaden. Her ideas were just as playful as they were modern. Her works showed not only the themes that she would explore in the following years, but also her essential sculptural orientation.

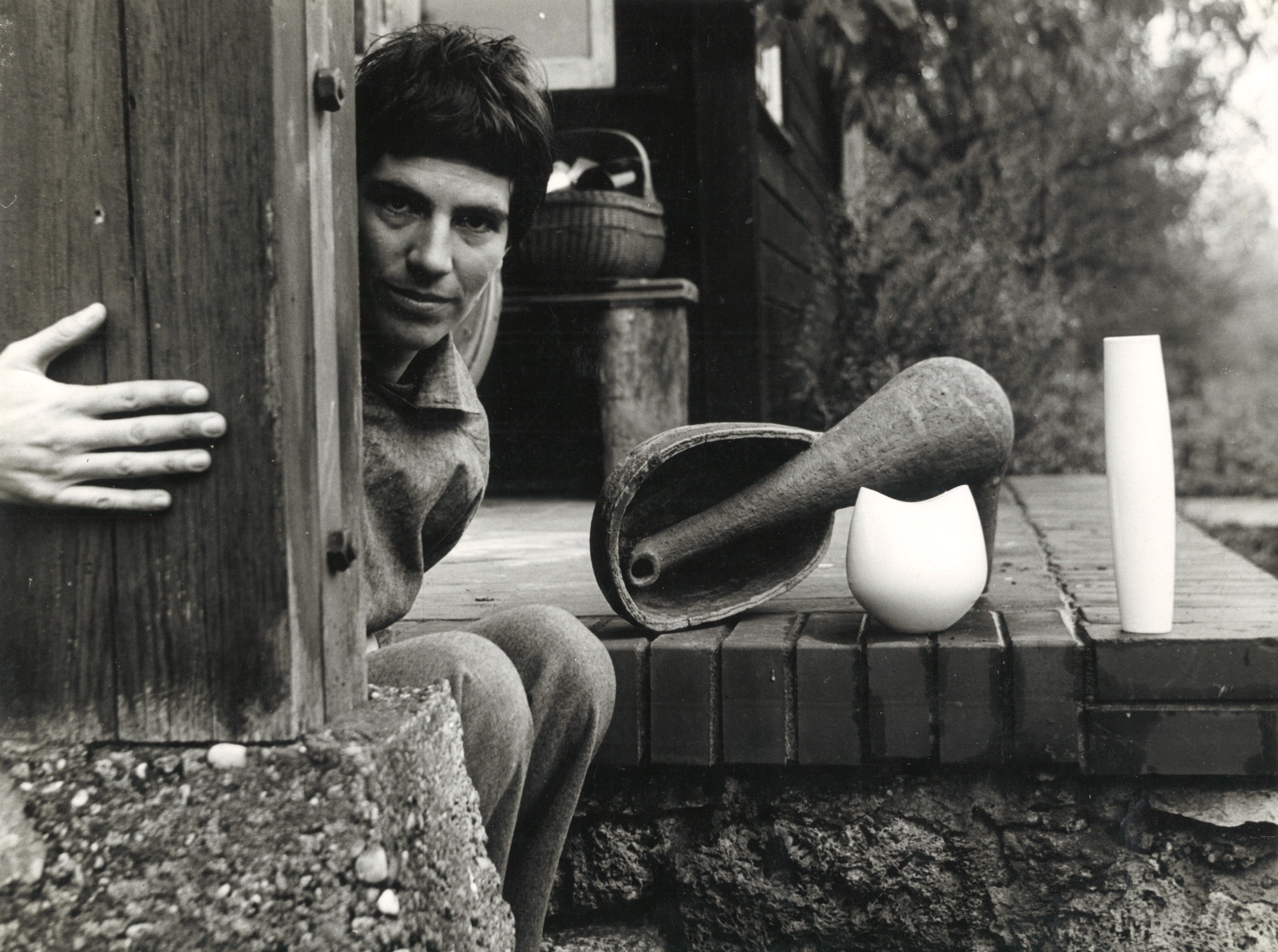

While she was still a student at the Werkkunstschule Darmstadt, she was the only one to be approached about collaboration with the Rosenthal porcelain manufacturer. Kuhn became a student trainee at Rosenthal and produced a range of designs30 for various vases (fig. 5). Her pieces were referred to in various magazine articles31 as carefree and joyous, reflecting the feeling of the times. The forms carried her unmistakable artistic handwriting, but the surface of the industrial porcelain did not fit with her own ideas.

Parallel to her obligations at Rosenthal, Kuhn took over the workshop in Lottstetten, set up by her professor Schroeder before his teaching appointment to Darmstadt. She assumed this difficult, high-risk course with great decisiveness. Together with Scheid, a friend from her student days, Kuhn began a four-year stint in Lottstetten in which she placed the sculptural and painterly interpretation of the female figure at the center of her creative thinking (see Kuhn’s Lottstetten work on display in fig. 6).

From the beginning, Kuhn worked towards meeting these goals, along with montages of various thrown pieces. With the thrown vessel as starting point, she sought to break up its axiality. Her innovations were based mostly on interpretations of the female figure, whose posture, movement, or mood were expressed in the shape of the vessel.

The formal starting point was the interaction of different volumes whose relationships to each other determined the expression. A large round vase with a long, slim neck connects with a calm form whose statuesque appearance stems from the merging of opposite elements—three-dimensional, primal form, vessel, and upright form (fig. 7, left). The vase Couple (Paar) also dealt with this theme, combining two figures in one form (fig. 7, right). The merest suggestion of breasts made the figurative intention clear, reinforcing the archaic moment. A Peruvian vessel shape, a so-called stirrup-form with a handle-shaped upper termination on which the pouring spout is attached, reminds us of a vase but suggests a figure at the same time.32 (See fig. 6, top row, right). Every so often, Kuhn created three-part forms apart from the single and pair vases, which in 1956 and 1957, took on a votive character. The themes simultaneously dealt with in these ceramics—of negative (space) and positive (form) volumes—were central to modern sculpture33 whose protagonists brought about exciting interrelationships between space and mass through open and closed forms. Not surprisingly in the exploration of the topic, Kuhn made connections to works by Henry Moore,34 whose bronze Inner and Outer Form, 1951,35 (Art Museum, Basel) Kuhn reflected upon in a small ceramic piece (fig. 8).36 In contrast to Moore, whose formal considerations—multiple perspectives while maintaining transparency of space—were paramount,37 Kuhn intuitively sought to convey emotional qualities such as the clearly protective gesture assumed by the outer mantle of the inner form.38 The subject matter, core, and crystallization point of her early work was the depiction of the figurative expressiveness, while simultaneously realizing formal ideas.39 The dissolution of symmetry and outline also enabled Kuhn to visualize movement.

By rhythmically assembling the differently shaped formal masses, Kuhn conveyed movement in space through their lively formal language. Many of her works speak of fun and joy of life, her names and her special titles such as Madam for many of her works for female figures convey humor and irony. Again and again, she surprised with original formal inventions.

The amusing multiple meanings of her vase-objects, such as Pensive (Nachdenklich) (fig. 9) or, Madam with Long Hair (Madam mit langem Haar) (fig. 10) with originally interpreted vessel details, which can in one way be interpreted as an arm supporting a head, heavy with thought, in the other as floor-length hair—both are the realization of fundamental sculptural considerations about the figure as vase and the vase as sculpture. Duplicity in itself always implies an opposite, which carries an alternative, complimentary, mirrored or opposite counterpart, in the same way as introversion and extroversion complement each other, while forming a contrasting pair at the same time. Lastly, the botanical references within Kuhn’s work reflect her close relationship to nature.

The Painting

In Lottstetten, the conditions were right for Kuhn to apply her glazing expertise from Darmstadt. The clay, which became water-tight at the comparatively low temperature of 1020 degrees Celsius, allowed the development of a rich color palette. Combinations of rust-brown, blue-violet, yellow-green, and eggshell white, as well as a smooth surface characterized her glazing style. She transferred the graphic linocut technique onto the ceramic applying the glaze then partly scratching it away to inlay with other glazes, which she again painted over, leaving bold, erratic, hatched, and cloudy, modulated surfaces. Through this buildup of layers, she imparted her ceramics with an unusual surface structure. Cubist interpretations of the figure influenced her painting on clay more strongly than her three-dimensional design approach, which was characterized by disassembly and rearrangement of single, amorphous, geometric elements randomly brought together and distorted.

She transformed her impressions of manuscript painting of the Early Middle Ages into her own expression through colorfulness, dark outlining, and deliberate gestures. One also notices that she was impressed, not only by the forms of the Peruvian ceramics and the tension within them, but also greatly fascinated the painting itself.40 These impressions can be seen in the sensitive way she related the darkly framed ornamental, figurative painting with the vessel form. In contrast to artistic interpretations on flat plates, Kuhn found significance not only in the texture and surface but in three-dimensional form, which especially animated her painterly continuation of the idea.

In her early work (1950s), Kuhn made no sketches before she applied her pictorial ideas, enabling her intuition and a certain spontaneity. Sketches were of importance to her later, after the priorities shifted to sculptural composition, “… because the play with the forms, in the resolution through the form,” as the artist herself said, “should not occur through the intuition alone.”41 Line and surface develop through the inclusion of random elements, such as drops of glaze arising from the direct glaze painting process of the final composition, which are first revealed by turning the vessel (fig. 11). Serene, reclining elongated figures stretch over the inner and outer wall of the vessel and emphasize the temperament of the three-dimensional form. The relaxed effect of the vase Couple (Paar) (fig. 7, right), for example, comes from the folded arms forming a frame, in a big painterly gesture from the neck downward toward the apotropaic gesture before the breast.

Overlapping, swinging, or geometrically broken lines were tools of visual language across all genres of 20th-century art. In this case, Kuhn’s linear elements are particularly closely related to those of Paul Klee, although there are also connections to Picasso—the defining person of the epoch—through certain marks typical of compositional elements of the period, for hair, hands, breasts, as well as the continuous line implying the body and the posture by way of association.

The spatial effect of this play of lines is also found in the steel iron and wire sculptures, which numerous artists worked with in the 1950s, especially after Jacques Lipchitz, Julio González, and Picasso first used it with the goal of liberating sculpture from solidity. Kuhn realized a whole series of wall pieces, which fulfilled figurative ideas through framing ceramic pieces in iron or enclosing empty space (fig. 12). Finally, Kuhn developed a two-necked vase to be interpreted figuratively, between which the head, made out of wire, is placed.42 This work remains her only attempt to continue drawing into space.

The Relationship to Modern Ceramics

Already in her youth, Beate Kuhn was impressed by the ceramics by Jan Bontjes van Beek (German, 1899–1969), which she had seen in catalogues of the Grassi Museum, Leipzig (fig. 13).43 Her admiration for Richard Bampi also led her to seek an apprenticeship with him. However, as Ekkart Klinge rightly remarks,44 their works had no formal influence on her own ceramic pieces; nevertheless, they are works which set her standards.

At the Frankfurt International Trade Fair (see fig. 6), where classical ceramic vessels in the tradition of the 1930s dominated (which many young ceramicists of her generation pursued)45 Kuhn’s colorful, painted, and sculptural vessels broke with tradition. Only the majolica manufacturer Erwin Spuler (1906–1964) from Karlsruhe, was represented with works of a comparable direction.46 In contrast to Kuhn’s matte glazes in strong, broken colors and her abstract figurative painting, Spuler worked with predominantly glossy, bright colors and ornamental decoration. His three-dimensional forms were successors of Max Laeuger’s (German 1864–1952) figurative majolica. Reviews of avant-garde ceramics by various international authors can be found in Keramische Zeitschrift (Ceramics Magazine),47 which document comparable approaches by Swiss48 and Italian ceramicists.49 In spite of differences, they confirm the preoccupation with the figurative vessel and the importance attached to glaze-painting.

In Italian ceramics, wares with colorful glazes fired at low temperatures in the tradition of majolica were the standard, further defined by an independent approach with the clay material. The determining factor of Italian ceramics was that artists freely choose between vessel, sculpture, wall piece, and painting.50 Naturally, Italian artists such as Lucio Fontana (1899–1968), or Gio Ponti (1891–1979), dealt with this medium.51 They were inspired by vessel-types of earlier cultures as well.52 Kuhn followed with great interest works by Guerino Tramonti (1915–1992), Nanni Valentini (1932–1985), Guido Gambone (1909–1969), and Rolando Hettner (1905–1978), who predominately made painted vessels (fig. 14). The common basis for the Italian artists and Kuhn was, however, the relationship to modern art in particular.

After England,53 Beate Kuhn encountered international ceramics once more at the Milan Triennial in 1954, to which she travelled by train for a day. In the same year, the Lottstetten workshop was represented with works by her and Karl Scheid at the International Exhibition in São Paulo.54 Works by the two ceramicists were also to be seen in 1955 in Italy at the International Competition of Ceramic Art in Faenza, where both were awarded a silver medal.55 At the International Frankfurt Trade Fair, Kuhn’s ceramics were bought by gallerists from Basel, Gothenburg (Sweden), Milan, London, and Lisbon.56 One of them was Adriano Totti from Milan with whom Kuhn held her first solo exhibition in 1957.57 At the wish of the exhibition’s architects, she drew freehand on the gallery wall with the greatest of ease. On the occasion of the exhibition, she met many of the Italian ceramicists in person with whose work she was already acquainted.

By the time she closed the workshop shared with Karl Scheid in Lottstetten, in 1957, and moved to Düdelsheim, where she set up her own new studio in close proximity to him and his wife, Ursula Scheid, Kuhn had asserted herself with her ceramics developed through skilled practice, intuition, and knowledge.

With the new studio came a change in materials. Kuhn still fired at 1020 degrees Celsius until autumn, 1964. In parallel, she introduced a white stoneware clay, which was fired at 1240 degrees Celsius. The decision to use one clay body or the other was made according to the way she imagined the colors to come should appear. The low firing temperature allowed her to maintain the color palette proven in Lottstetten, while she had to develop new glazes for the higher temperature. At the beginning, the only glazes available for high temperature ranges were a series of smooth glazes suitable for domestic tableware production. Until 1962, she carried on her work with the language developed in Lottstetten, although certain changes indicated a new start. The compositions became more restful. The asymmetry was slowly left behind. The female figure was replaced by additive, geometric forms that became the great continuity of her oeuvre to be developed with endless fantasy from wheel-thrown elements. The glazing changed from contained, colored areas to abstract, natural color gradients. In 1963, the transitional phase was complete. The coming works pointed Kuhn’s way to free ceramics, free to be determined only by her imagination and not constrained by any specific influence, tradition, or expectation. The ceramic object was born (fig. 15).

Dr. Sabine Runde, Art Historian, has focused her research work on the subject of craft and applied art for nearly 40 years. At the Museum Angewandte Kunst Frankfurt am Main, she has worked as volunteer, freelance employee, curator, deputy director, provisional management, and most recently as Senior Curator of Applied Art from the Middle Ages to the Present. As curator of numerous exhibitions, she conveyed the relevance of applied art to the public through new perspectives. Most recently, she edited Arts and Crafts is Cactus, a survey of the collection of the Museum Angewandte Kunst since 1945.