There are many kinds of photographs, and each one shapes our perspective of the camera and image-making differently. For today’s #TourTuesday, we’re exploring a few of our favorite vernacular photographs from our collection. Vernacular photography is an umbrella term for photographs made by hobbyists, press photographers, and studio practitioners. It can include anything from snapshots of everyday life (like the ones in your family photo album) to commercial portraits and advertisements in magazines.

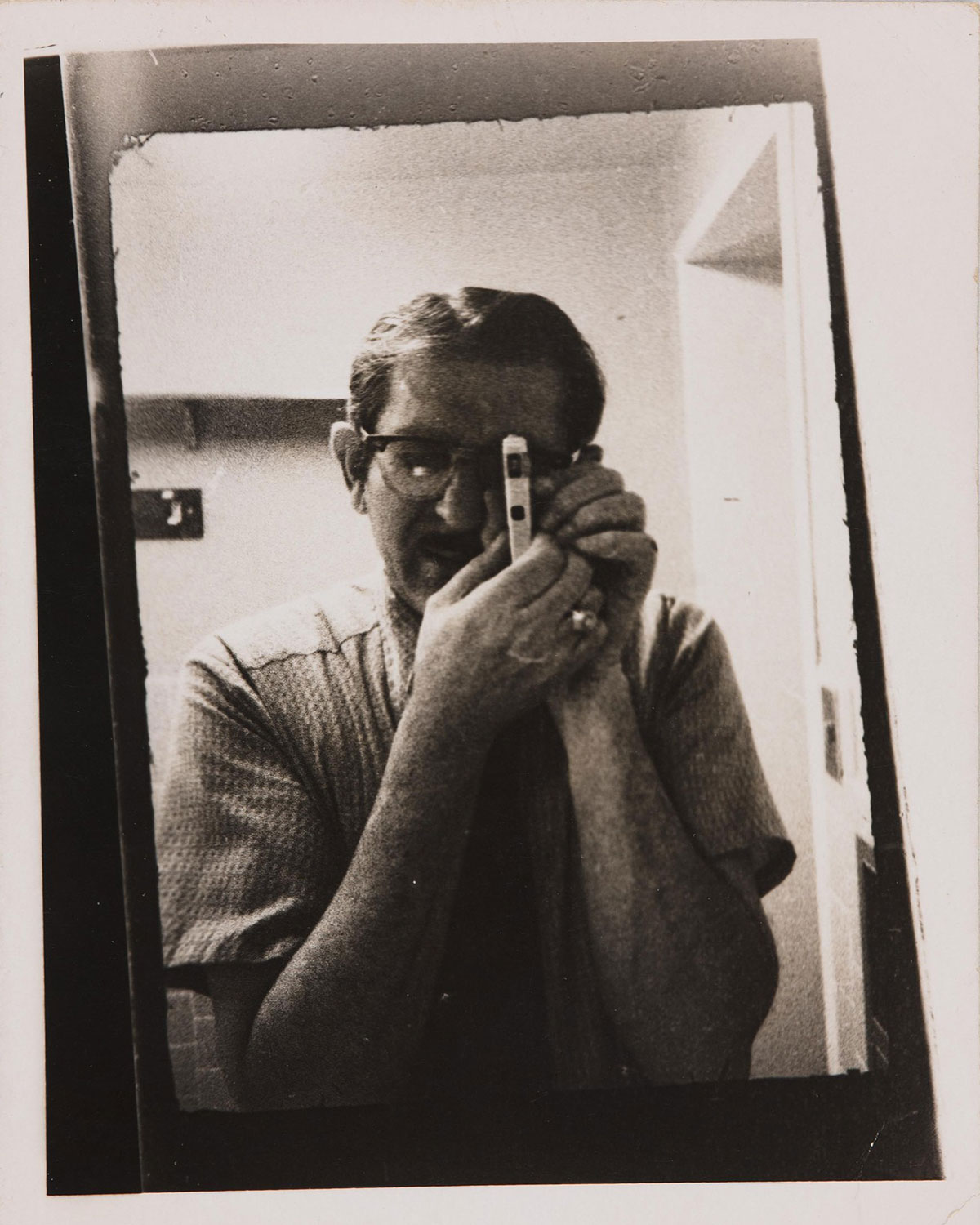

Look familiar? Like the ubiquitous bathroom selfies of today, this picture by an unknown person captures his own reflection in a mirror. The camera appears to be a Riga Minox, which is sometimes called a “spy camera” because it’s the size of an index finger. It was invented by the Baltic German inventor Walter Zapp in 1937, and a lightweight version became popular following World War II.

This type of photograph, known as a cabinet card, was popular from the 1870s until the end of the 19th century. The image is a standard size (6 ½ x 4 ½ inches) and is typically mounted to a piece of cardstock, which includes the name of the photography studio on either the front or the back in a highly embellished style.

This photograph, taken at photographer Orlando Scott Goff’s studio in Dickinson, North Dakota, depicts a member of the Buffalo Bill Soldiers—four all-black peacetime regiments that were organized in 1866 to support the nation’s westward expansion. Note the formal stance, the crisp uniform, and the decorated background. This kind of portrait would have likely been shared with family as a keepsake.

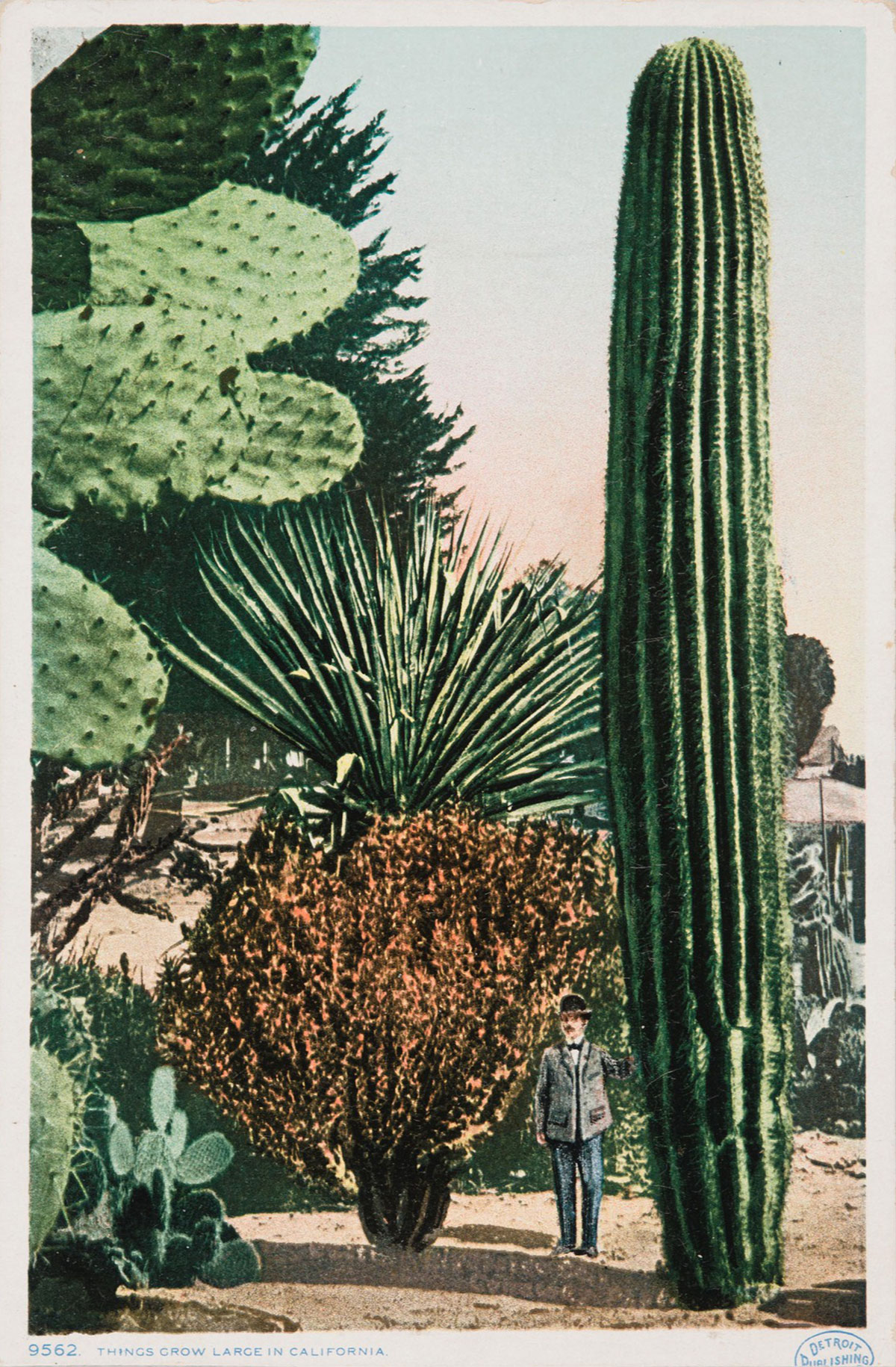

A man appears to stroll through a forest of 30-foot cacti. But does he really? Early 20th-century postcards known as tall tale postcards or “exaggerations” utilized crafty techniques that can be understood as Photoshop before computers. Photomontage, one of the most popular methods, consists of cutting different images out and gluing them into the same composition. Suddenly, a small figure and a giant cactus stand right next to each other for a mind-boggling comparison. With the cheeky caption at the bottom, “Things Grow Large in California,” it’s clear we are in on a good joke.

Detroit Publishing Company operated under that name from 1910 until 1924, making this postcard around 100 years old! Who would you send it to?

Selfies go back further than you might think! This is just one of many photographs in our collection in which the subject has written “me” or “myself” on the image. This young woman even included the year it was taken—1931! The writing on the border paper and the use of photo corners, make it clear this selfie was meant to be seen and enjoyed.

This image was taken during the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. This photograph of an endless sea of automobiles offers a nostalgic view of a time when cars were the future. Just by looking, we can feel transported to another time and reflect on the sort of awe that might have motivated this photographer. While the purpose of the picture is unknown, as one of photography’s biggest champions, John Szarkowski said, “A photographer’s best work is, alas, generally done for himself.”

So, go ahead and take a picture! Who knows? 100 years from now it may end up in a museum’s vernacular photography collection.