By Damon Young

The home my wife and I share sits in an impressive building on Fifth Avenue. If I peer out our kitchen window and glance right, I’ll see Dinwiddie Street. A 15-second drive up Dinwiddie leads to Centre Avenue. The Hill House, the Thelma Lovette YMCA, the Alma Speed Fox Building, and perhaps the most politically contentious Shop ‘n Save in the country all sit within a five-minute walk. We do not live in the Hill District. This awkward stretch of land that exists between Oakland, downtown, the Hill, and the South Side is technically called Uptown—a differentiation that definitely seems to matter to pizza delivery men. But this apartment we live in—located in a building that was once Fifth Avenue High School and is now the Fifth Avenue School Lofts—and the hows, whys, and whats of how people came to live in this long-dead school building, tells a Hill District story. A Pittsburgh story. A black America story. A Teenie Harris story.

The story of how the Fifth Avenue School Lofts came to exist is a complicated one that I will attempt to simplify. It is also contentious. There will be people who will vehemently disagree with what I’m about to say, either claiming that I’m intentionally disregarding important context or attempting to skew facts to promote an agenda. I am doing neither. What I am doing is telling this story how I’ve come to see it.

The Fifth Avenue School Lofts is one of a dozen or so upscale inner-city redevelopments that have taken place in Pittsburgh over the last decade. These redevelopments have been spurred on by the city’s status as an emerging hub of business, technology, education, and culture. Rarely does a month pass without Pittsburgh ranking near or at the top of some list of the country’s best cities. This helped cause the city’s decades-long population decline to plateau and, according to the latest census, reverse. People are moving and staying here now. Young white professionals, specifically. And they need somewhere modern, urban, accessible, and cool to live; and what’s more modern, urban, accessible, and cool than a refurbished schoolhouse a half-mile from town?

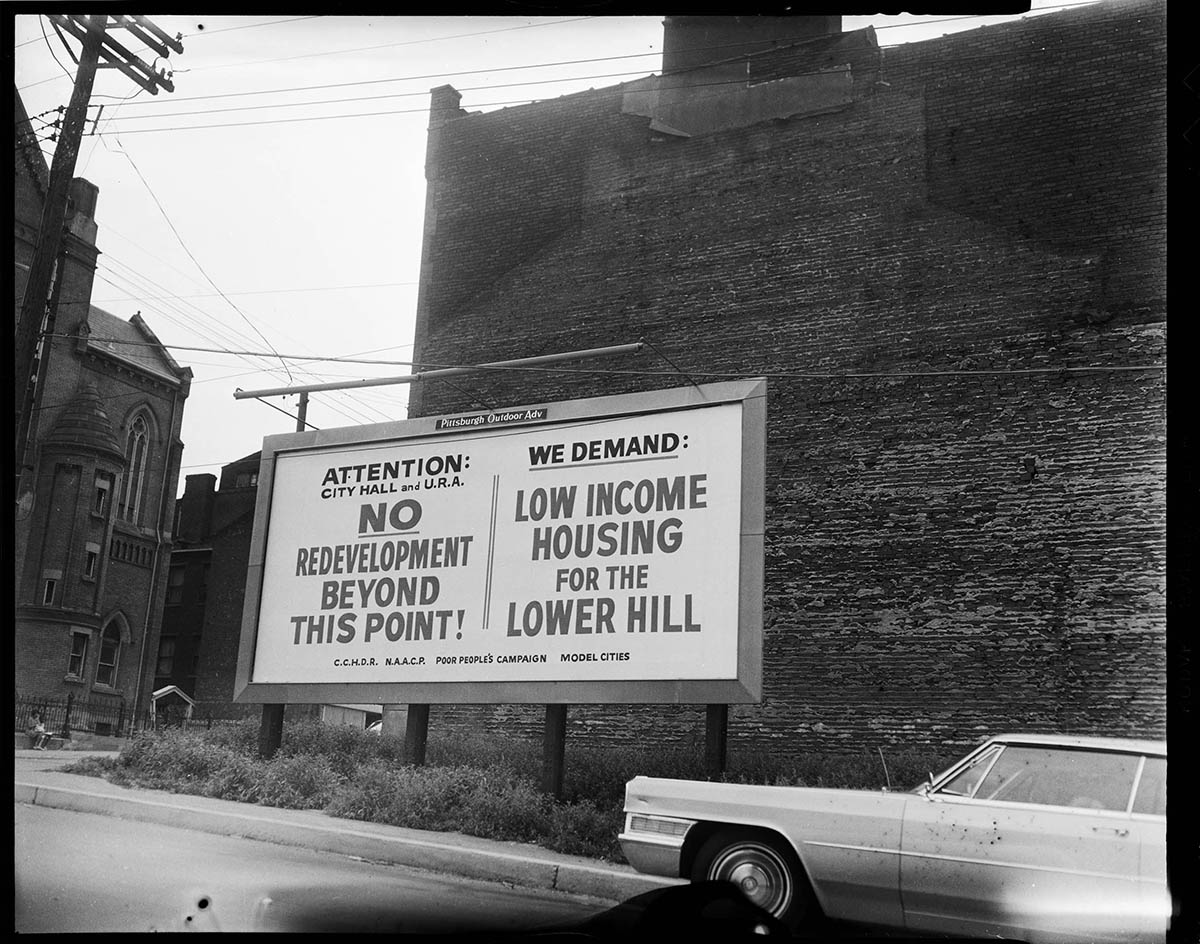

These lofts exist here because Fifth Avenue High School—a dominant city sports power that served the lower Hill and includes Cyril Wecht among its alumni—was long vacant. The Fifth Avenue High School building was long vacant because it was closed in 1976. It was closed in 1976 because there weren’t enough high school–aged kids in the lower Hill to fill the classrooms. There weren’t enough school-aged kids in the lower Hill to fill the classrooms because the population of the lower Hill experienced a sharp decline. The population of the lower Hill experienced a large decline because many of the lower Hill’s residents were forced to move—displaced to East Liberty, Homewood, and other parts of the city. Many of the lower Hill’s residents were displaced because the city of Pittsburgh prioritized creating space to build the Civic Arena over the thousands of residents and hundreds of businesses already existing in that space. The Fifth Avenue High School Lofts exist today because the vibrant and diverse Hill District immortalized by Teenie Harris no longer does.

The Hill District itself is still there today. Bedford, Wiley, Webster—these streets aren’t going anywhere. There are several thriving businesses. A few renowned churches. And hundreds of homeowners. Black homeowners who’ve either been able to hold on to older properties or take advantage of some of the recently built homes. The Hill is not dead. It will continue to survive. But the level of survival has changed. Today’s Hill District is dealing with the effects of post-colonization—the resource drain, the property plunder, the native population drop—without ever actually being colonized.

The Pittsburgh chapter in the centuries-long black American story is told with a drive on Centre from the gleaming new Consol Energy Center to the soon-to-be-developed-into-more-modern-urban-accessible-and-cool-apartments Schenley High School building—million-dollar bookends evidencing the city’s oft-publicized revitalization. Each underdeveloped block between them a different page; each empty corner a different footnote. All articulating exactly why the recent #BlackLivesMatter campaign is so vital. And so controversial. Because America has long operated with the latent belief that black lives, and black bodies, and black families, and black businesses, and black properties, and black histories, and black legacies do not.

I imagine that the thousands of people photographed by Teenie Harris in the 1940s and 1950s—schoolteachers and bandleaders; coal miners and Pittsburgh Crawfords; nurses and nannies; politicians and Charlie Parker—would have predicted a better Pittsburgh in 2015. And they would have been right. The city is better. Much better. The population is growing. The air is clearer. The water is cleaner. Black people can (finally) shop downtown. It’s one of the best cities in the country. Its transition from steel town to technology hub has been phenomenal. The parks are breathtaking. The cultural district is world renowned. The topography is, and will always be, beautiful. And even the (black!) president loves Pamela’s.

And it’s even better if you’re not black.

Damon Young is the founder and editor-in-chief of VSB Magazine, as well as a contributing editor to EBONY Magazine (digital). His work has been featured in numerous publications, including Complex, The Root, Slate, Essence, and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.