When Macy’s closed its historic downtown store in September it also shuttered in the ghosts of the former Kaufmann’s department store, a Pittsburgh institution which had been receding in the city’s collective memory for decades.1 Much has been made of the fact that Kaufmann’s was more than a store. It was part of a nationwide phenomenon that today seems completely foreign to us—department stores were centers of high art and culture, not only accessible to the city’s populace but intensely engaged with it. As a museum, we should be both indebted to, and interested in the work that Kaufmann’s did in Pittsburgh—it is a case study that reveals how to spark the public’s interest in art and quality craftsmanship, and win a city’s personal loyalty to an institution. Kaufmann’s aimed to help customers build their own design consciousness, yet the store’s management also treated their customers holistically. Kaufmann’s renowned window displays regularly presented an abiding interest in the personal growth and well-being of their customers. And the displays were often part of a cultural and civic circle that encouraged attaining “the good life,” not necessarily through material possessions, but through a rich and expansive interior life.

First and foremost, it was crucial to Kaufmann’s that their buying public be worldly and wise. If you could not afford foreign travel on steamships and trains, then Kaufmann’s encouraged you to explore the world through books. One example of the store’s yearly Christmas greeting “To the Little Children of Pittsburg” [sic] is a small book, Auto Trip to Foreign Lands (ca. 1915–1919). It depicts a young child in a sailor suit holding a toy ship and sitting on a steamer trunk covered in international labels, while inside the book speaks to the young reader like an educated adult and future citizen of the world.

In the books, a host of destinations are visited including London’s Houses of Parliament; Paris’s Arch de Triumph; Italy’s great cities and monuments (A Visit to Rome is an event in one’s life); and the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, which includes this rather whimsical passage: “These little sketches are put in this book, in order that our young tourists may look up other scenes in the same cities, when they get back home, and tell their schoolmates what they saw across the sea in foreign lands. Pittsburg is full of libraries and, in any one of them, our boys and girls can travel from pole to pole, and from Allegheny to the Equator. Books are great educators. Read all you can about Berlin, Germany’s great city.” The guide includes Egypt’s Port Said, as well as a pagoda in China where bells blow in the breeze. The text evokes the tinkling of chimes and casts a spell on the young reader, only to bring them back home to America via Big Tree, California, and an image of an automobile driving through one of America’s natural wonders—the giant sequoias of Northern California.

This hallmark emphasis on globetrotting puts the department store’s ambitious International Exposition of Arts and Industries into fuller context, along with the desire to bring far-flung examples of world ornament—much of it historical—to Pittsburgh customers. Following the International Exposition in Paris in 1925 (a landmark event that coined the term Art Deco), Edgar Kaufmann presented his own grand exposition. Store representatives reportedly “raked the universe” for historic design and ornamentation and “winnowed world corners” for modern merchandise that Kaufmann’s displayed throughout its sales floors in November 1926.

In 1930, Kaufmann’s again blurred the line between department store and museum when it installed a series of ten murals by artist Boardman Robinson on the theme of “Art in Industry.” Circling the first floor, there were scenes depicting imagined moments of international trade from ancient era up to the 20th-century. Their monumental scale and lofty (if sometimes culturally insensitive) themes, rendered in a tempered modernist style, were meant as a gift to the city. Edgar Kaufmann actively solicited feedback from civic, educational, and journalistic leaders about the murals’ community impact to use as promotion. A. C. Robinson, President of Peoples-Pittsburgh Trust Company enthusiastically responded:

Consciously or unconsciously, the effect on the customer is to raise his or her own standard of thought and desire for better things. As regards the store, it seems to me that it will raise your customers’ standards as to the quality in what they buy and will also inspire them to desire for things of beauty so far as usefulness will permit. Like the presence in a city of an art museum, no one can estimate how far reaching the influence of such things may extend, and how they may leaven the lives and ideals of countless individuals.2

Between the high ceilings, mural-filled sight lines, and Benno Janssen’s sleek modernist transformation of the vertical pillars (using Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company’s structural glass tiles), Kaufmann’s merchandise-laden first floor befitted a cultural palace for the 1930s.

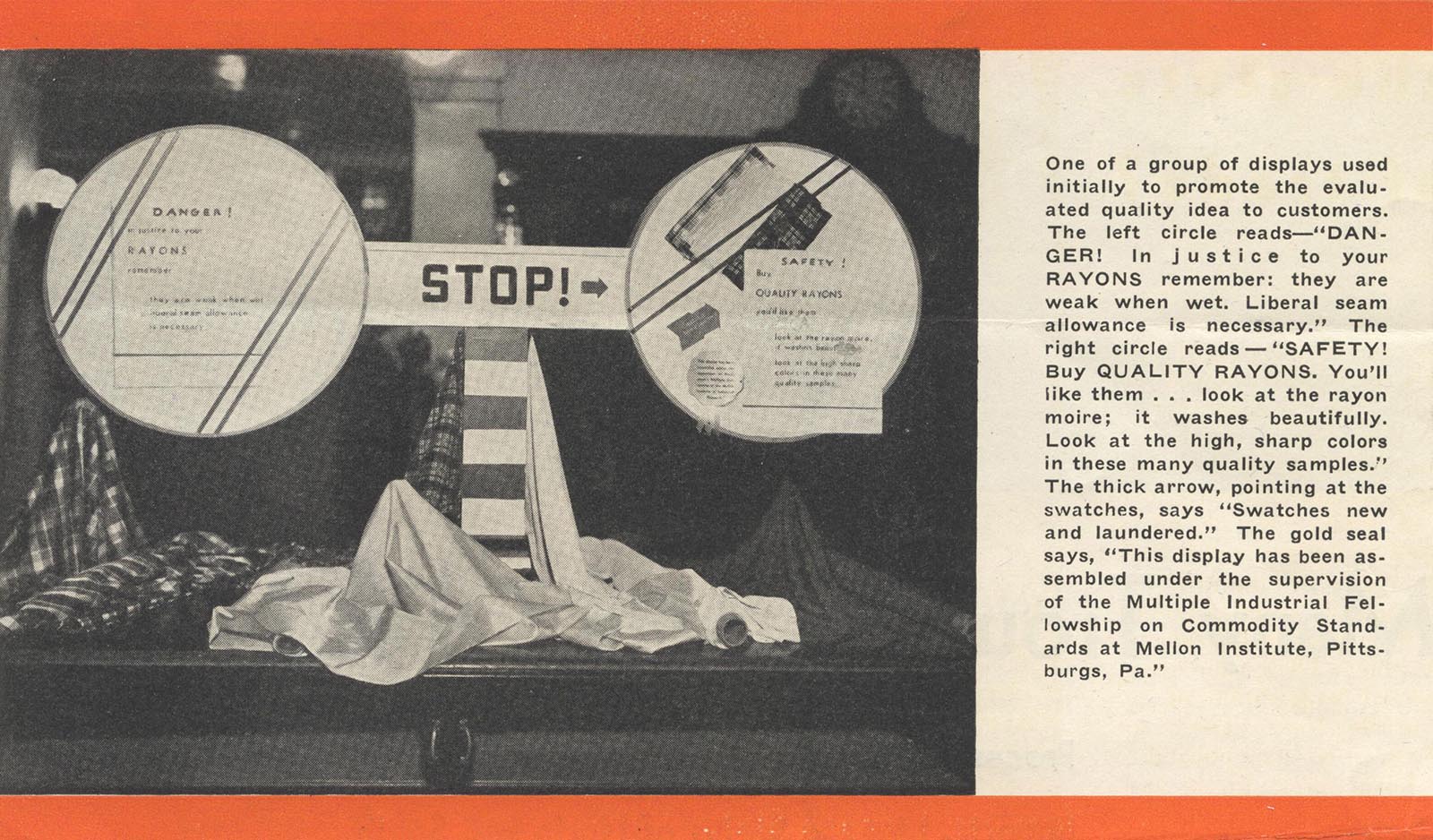

Simply putting high-end merchandise in view of commissioned artwork, however, does not guarantee that customers will absorb artistic sophistication. A staff equipped to convey helpful information about choosing and caring for materials—everything from cutting edge man-made fabrics to glass, ceramic, and leather goods—became finely orchestrated at the store. Staff conveyed product information, framed as cutting-edge science that came from the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research.

World War I had siphoned off department stores’ employees, creating a vacuum to be filled. The Research Bureau, launched in 1918, was the first college department in the United States dedicated to retail as a branch of study. Funded by collaborating department stores (led by Edgar Kaufmann, Sr.), the Bureau began at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (within the Division of Applied Psychology) and transferred, after a successful five-year trial run, to the University of Pittsburgh in 1923. The Research Bureau promoted retail sales positions as prospective careers, and fueled a closer connection between the community and its department stores. Top-selling salespeople spoke to university classes and, in return, member stores benefitted from the Research Bureau’s market studies and scores of new professional handbooks. Aimed first at college students, the program later becoming a vocational training program for high school students as well, and helped to retain many students. Initially focusing on effective selling techniques, courses expanded to include store operations, advertising, merchandising, and strong communication and language skills (a key addition to high school level-training).

Kaufmann’s also hosted evening classes, or “Retail Institutes,” as continuing education for employees of the bureau’s cooperative stores.3 In 1936, Peter Muller-Munk, the new industrial design instructor at Carnegie Tech, spoke on “Design—the New Sales Factor.”4 Aimed at executives in home furnishings departments, Muller-Munk presented samples of kitchen and table wares, furniture, lamps, and packaging to teach about merchandise design, how store executives might “influence production at the factory,” and how to properly evaluate the “modern versus the modernistic.” Edgar Kaufmann, jr. (he preferred to lowercase “junior”), had returned to work at the family store in 1935 and soon rose to merchandising manager of Kaufmann’s Home Department, so he would likely have been in the audience, preparing for his curatorial appointment at the Museum of Modern Art in 1937.

Edgar Kaufmann jr. was not the only design historian on staff, however. The Retail Bureau’s 1928 publication Store Positions Requiring Art and Clothing Background recommended hiring merchandising, advisory, and training stylists (representing the whole gamut from store buyer to floor seller) with instruction in English, psychology, education, design and color, costume design, historic costume, clothing construction, textiles, history of art, home decoration, history of furniture, and public speaking—in effect, many of the same qualifications for museum professionals today. Merchandising stylists, in particular, were expected to attend “significant art exhibitions in order to keep thoroughly in line with the influence the fine arts are having on style trends in merchandise.” They should also know their community and take part in civic events, including programs of clubs, schools, and colleges. Information about customers trickled upwards to buyers, while qualities of goods flowed downwards to sales staff who helped patrons select merchandise to best suit their needs and tastes.

In order to have the most highly trained sales staff, armed with the latest information about merchandise and its materials, Edgar Kaufmann, Sr. also created the Commodity Standards Fellowship at the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research, a program of “merchandise evaluation” that scientifically developed and tested goods. This insured merchandise was of high quality, and determined how to best clean and care for these items, information then imparted to customers. Through the Mellon Institute, Kaufmann’s also gained unrivaled access to the entire institute’s research, where more than 60 industries tested products. Drawing on the sales power of such up-to-the-minute research, Kaufmann’s created the Bureau of Science within the store, where both impactful displays (created by art school graduates) and teams of women provided technical information to sales staff and customers.

Science could instruct a mother how best to launder a delicate blouse or select rugged children’s clothes, but it was also part of overall optimism. As a way to celebrate its “65 years of progress and fidelity to forward-looking ideals,” Kaufmann’s windows highlighted recent milestones in the history of mankind with “Peaks of Progress: 1935–1936,” a “window pageant of world achievements.” Selected by historians from local universities, such moments proved that facts can be fabulous—The Second Byrd Antarctic Expedition revealed that Antarctica is a single continent and measured the depth of the continental ice cap; a giant telescope lens allowed man to see three times farther into the heavens and photograph them ten times faster; the highest ascent in the largest hot-air balloon in 1935 led to photographs of earth’s curvature; and French ocean liner Normandie (June 1935) broke the Trans-Atlantic speed record. This was fortifying, optimistic thinking in the heart of the Great Depression. Scientific knowledge—well curated—offered sublime glimpses of the world, with its graceful arcs and deepest depths.

Skipping over decades, the department store’s newsletters reveal an ongoing commitment to education and empowerment. In 1968, Kaufmann’s founded a program for women in business called Kaufmann’s Triangle Corner Ltd. KTC (for short) celebrated Pittsburgh’s working women and fostered a pioneering tribe of professionals in the fledgling days of the women’s liberation movement. The program sponsored classes on working while pregnant, how to find quality childcare, as well as “Resisting the Superwoman Syndrome.” It also celebrated “Outstanding Women in the Fashion Industry,” particularly those that designed clothing for business women as a growing market segment. Local artist and industrial designer Irene Pasinski designed the award, and was Kaufmann’s Woman-of-the-Year in Art for 1970.

Much like the 1930s Retail Institute, Kaufmann’s 9th-floor college classrooms offered multi-week series of business-related courses taught by faculty from across Pittsburgh’s universities. Among other course offerings, women could prepare thoughtfully for the 1984 election—the year Geraldine Ferraro ran as vice presidential candidate to Walter Mondale—by attending lunchtime discussions of world affairs and the presidential candidates’ policies. For the Annual Pittsburgh Women’s Career Network Day, Pittsburgh native Barbara Feldon returned as a keynote speaker at Kaufmann’s. The actress played agent “99” (the wits behind the bungling male agent) from 1965–1970 on “Get Smart.” With her cool intelligence, modern style, and Audrey Hepburn good looks, Feldon embodied what Kaufmann’s encouraged in its female customers—the whole package of style, confidence, and brains.

What does this brief circuitous romp through department store history teach us? As museums struggle to compete with an intellectual and popular culture tiled by computer screens that offer a hyper-saturated world of visuals, these historic institutions are actively reevaluating their role in a 21st-century world. What can Kaufmann’s department store teach us? Apparently quite a bit about impresario-style showmanship, making knowledge fashionable (and therefore hotly desirable), incorporating contemporary trends while promoting timeless aesthetic virtues, addressing broad audiences with elegantly intelligent themes, and offering heartfelt care for its patrons’ personal empowerment that breeds loyalty.

Special thanks to reference archivist David R. Grinnell for sharing materials from the University of Pittsburgh’s Archives Service Center.

The role of Kaufmann’s department store as a progressive cultural institution is further discussed in the exhibition Hot Metal Modern: Design in Pittsburgh and Beyond, currently on view in the Charity Randall Gallery at Carnegie Museum of Art from September 26, 2015 to October 2, 2016. To learn more about this period of sweeping change in the city’s history, visit the Pittsburgh Modern story archive.

Catherine Walworth is an art historian and arts writer. Her areas of interest include Modernism in its many forms, particularly avant-garde painting, design, fashion, and early film. She received her Ph.D. in 2013 from the Ohio State University and is currently developing a book on Russian Constructivism and post-revolutionary material culture. Currently based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, she is a curatorial research assistant in the Decorative Arts and Design department at Carnegie Museum of Art, where she is at work on the exhibition Silver to Steel: The Modern Designs of Peter Muller-Munk. Walworth has conducted studio visits and written art reviews for print and online publications since 2003.

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.