When I was young, my father used to set up a darkroom in the different houses and apartments where we lived—first in Westmoreland County, later in the suburbs south of Pittsburgh. Using his Minolta Sr-T 102, he taught me how to make a proper exposure and how to compose shots.

At the time, photography was an integral part of my father’s life. He made lasting portraits of my mother, sister, and brother, as well as close family friends. My father also documented issues that were important to him, like the organization of a union at Western Psychiatric Institute, where he worked as an aide in the 1970s. But as he grew older, and as his time for photography dwindled, he eventually boxed up his equipment and stored it in the attic. Watching my father work with a camera and film in those early years, however, left an indelible impression—instilling a fascination for not only the power of image-making, but the process behind it.

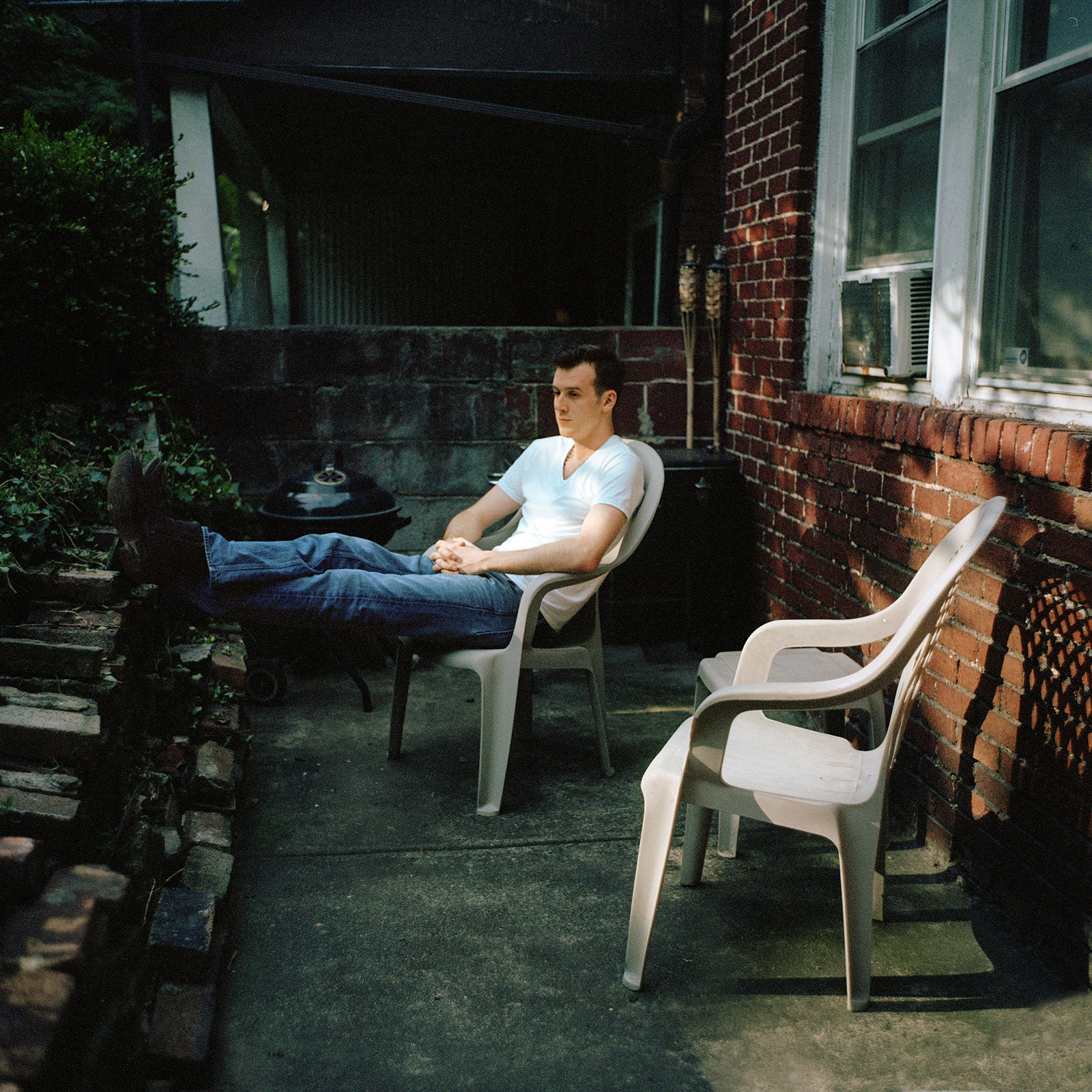

As a photographer, I learned early on that making pictures is about experimentation. Several years back, after buying a house in Greenfield with my wife, I unearthed my father’s photo equipment and built a makeshift darkroom in our basement. Instead of relying on digital, I opted to learn fundamentals. I began using my father’s old Minolta and committed to shooting film, making prints, and learning as I went. After a few seasons making pictures in and around Pittsburgh, I felt more comfortable in my approach. It was these early experiments that inspired Homespun, an ongoing series I’ve been working on that documents the physical and cultural aspects of Western Pennsylvania.

Homespun is a word often used to describe the unrefined quality of an object. However, it can also imply a unique or personal touch. It is a term that can convey self-reliance or lack of sophistication. With the images for Homespun, my goal is to provide an honest depiction of the physical and cultural character of Pittsburgh—shining a light on the perseverance of the city’s people, and chipping away at its stereotypes.

As a teenager, I witnessed the dismantling and disrepair of the structures that represented the identity of an entire region—from steel mills, coal mines, and manufacturing plants, to the grocery stores, social clubs, and corner bars frequented by local workers and their families. I would often hear Pittsburgh described as dirty and broken, a place to be avoided. We were stereotyped as provincial, holding on to glory days that had long passed. That sentiment was often in direct opposition to my experiences. The back and forth between personal experience and public opinion created feelings of isolation and alienation. I grew to realize that I live in a place that is coarse yet captivating.

The physical environment served as a reminder that our accomplishments are fleeting in the cycle of change. Which in turn has impacted the psychological aspects of the city’s cultural memory and its collective identity. Home, it turns out, is more than a place—it’s a constantly evolving state of mind.

Jake Reinhart is a photographer from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He earned a B.A. in Sociology and a Juris Doctor from the University of Pittsburgh. He is a recent recipient of a Pittsburgh Filmmakers Emerging Photographer award; An Artist Opportunity Grant from the Greater Pittsburgh Art’s Council; and was a semi-finalist in the Philadelphia Print Center’s 89th annual international photography and print competition. Jake has assisted photographers such as Zoe Strauss, Mark Neville and Melodie McDaniel. He has exhibited his photos in Pittsburgh, Nashville and San Francisco. His work explores the influence economic change has on the individual and the community.

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.