In the period immediately following World War II, artists reckoned with a dramatically shifting global order. Some artists responded to the tragedy of war with innovative, even destructive forms of abstraction; others reinvented art’s relationship to nature and the self.

For today’s tour, we’re exploring works featured in A New Horizon, a section of Crossroads: Carnegie Museum of Art’s Collection 1945–Now, which you can visit once we reopen to the public on June 29!

“When I begin I have no idea where I am going. All I can see is a certain spatial constellation from which lines of strength gradually emerge … I perceive something that I call, for want of a more appropriate word, the ‘emanation’ of form; I gradually absorb it and as it were inhale it.”

—Eduardo Chillida

Spanish Basque sculptor Eduardo Chillida embraces the contradictions between the solidity of his chosen material (iron or steel) and the sense of ethereal movement captured by his sculptures. In this work, rough-hewn bars of iron appear to splinter and flutter as if caught in a storm.

In his use of direct welding, Chillida rejected classical traditions of sculpture—molding and casting—and used an improvisational process that echoed how his peers experimented with gestural forms of abstraction in painting in the 1950s and 1960s.

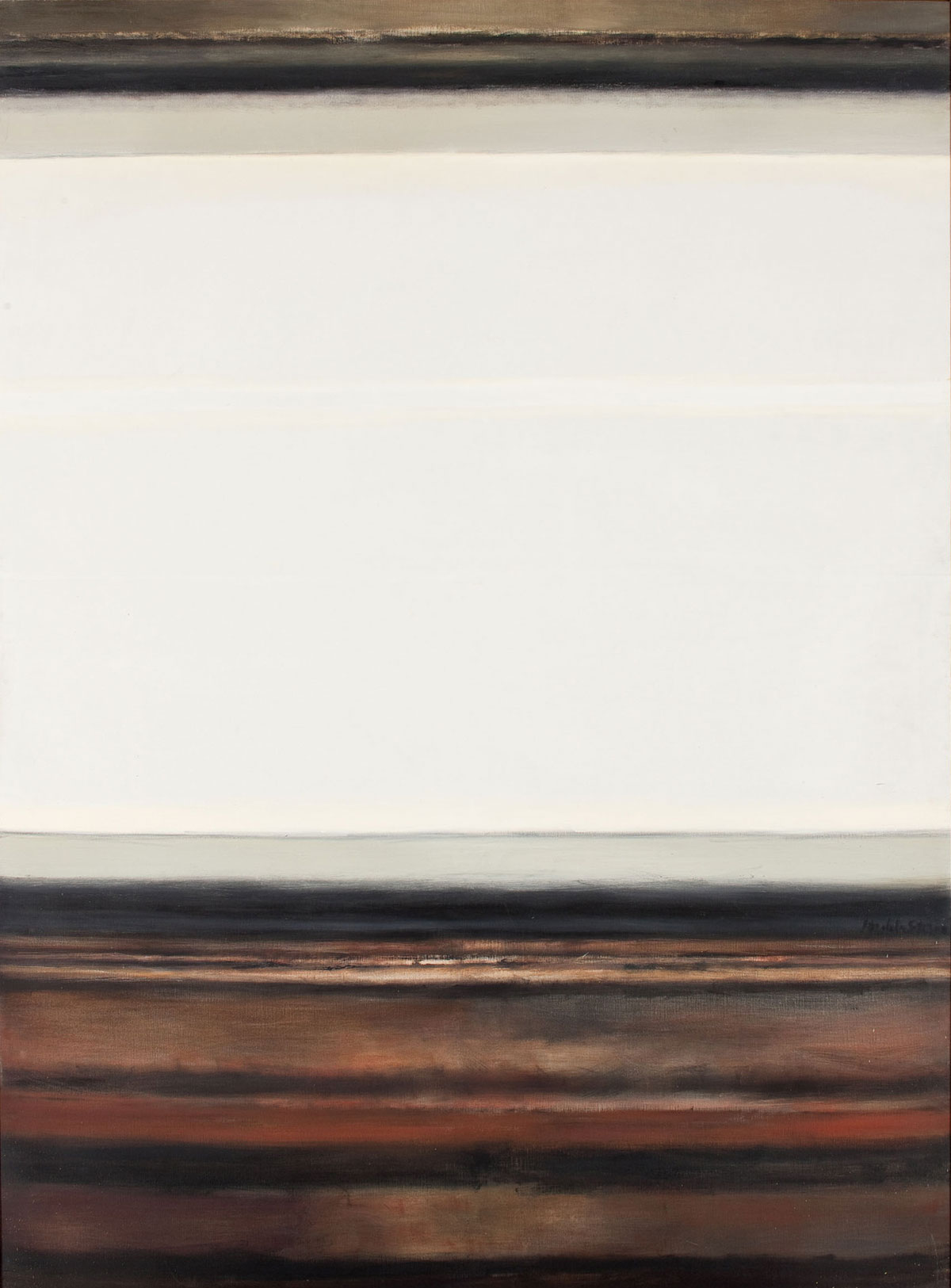

“I get enormous pleasure out of very small contrasts. I don’t know to what extent it is an emotional experience or an intellectual pleasure…This is what I enjoy — these very, very subtle distinctions in values.”

—Hedda Sterne

Although most often remembered for her inclusion in the famous 1951 Life Magazine photograph of “The Irascibles”—Abstract Expressionist artists who challenged the traditional tastes of museums at the time—Hedda Sterne was an artist free from strict categorization. As other objects in Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection can attest, her style shifted over the course of her career unveiling a persistent process of curiosity and discovery.

Horizon II explores the subtle contrasts between lines of color. Even among the seemingly white block, there are nuances of shifting pigments from white to cream to very faint gray. This painting is part of a group known as Vertical-Horizontal. Completed in the 1960s, these works zero in on the “secret significance in the depth of the ordinary.”

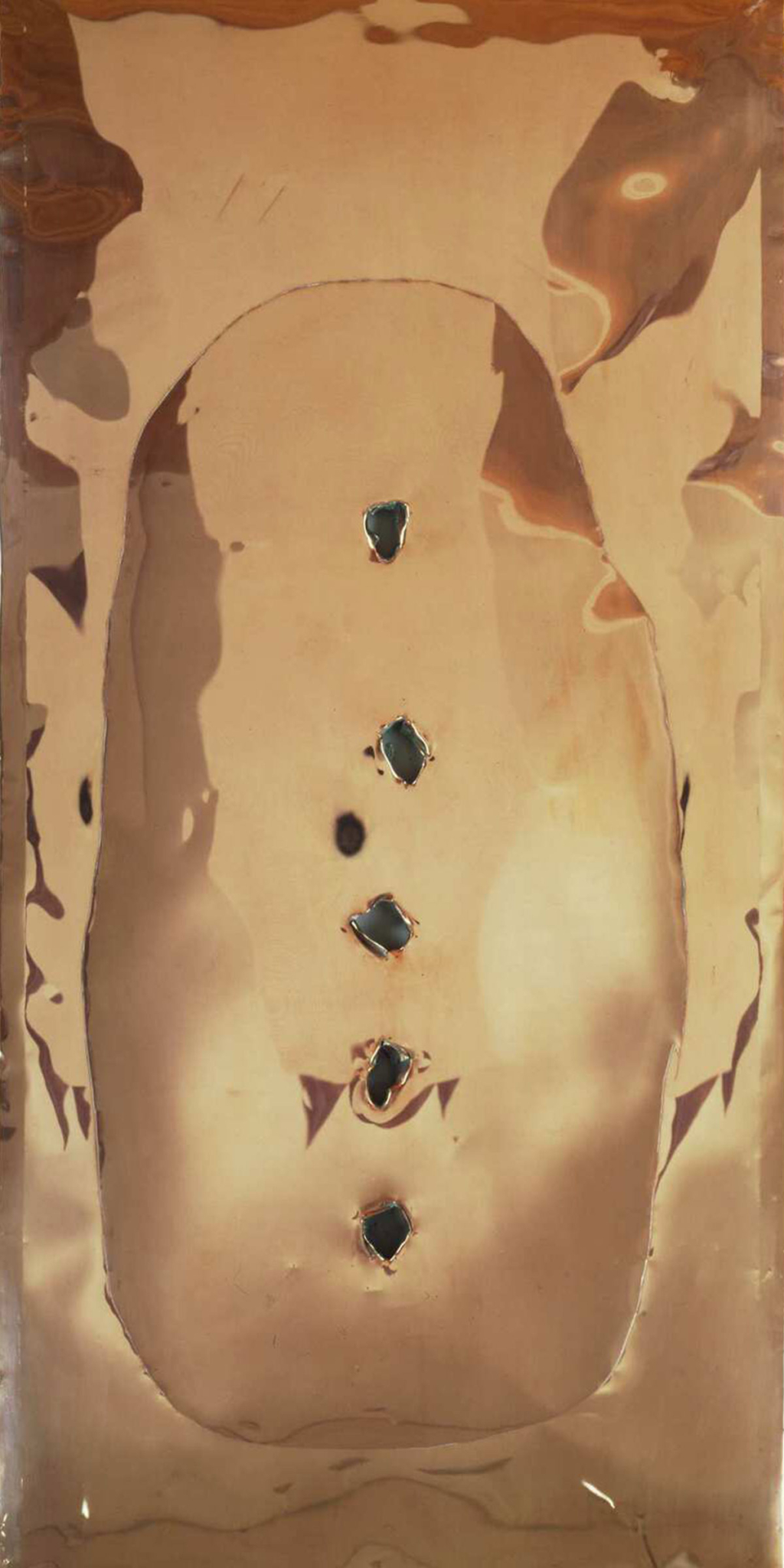

In 1949, Lucio Fontana began a series of paintings based on slashing the canvas with a razor blade, which revealed the space behind the surface. This provocative gesture proved decisively influential for a generation of artists following World War II, who sought to reexamine and push the conventional limits of art.

In a group of bold manifestos, Fontana expressed his ambitions to create an entirely new aesthetic, one that might transcend matter and extend pictorial space. He would settle for neither “paintings nor sculptures, but forms, colour [and] sound through space.”

An abstract painting with a muddled, off-white background layered with grey and small dabs of gold and a large black zig zag shape featured through the middle.

Japanese painter Jiro Yoshihara is best known as the founder of the Gutai Art Association, an innovative collective based near Osaka from 1954 to 1972. In response to World War II, a period when Japan’s totalitarian regime stifled individual creativity, Yoshihara advocated for experimental originality among his peers.

Rather than use the conventional word kaiga (painting) to describe their work, the Gutai artists embraced the more general term e (picture). In doing so, they created new possibilities for transcending the limits of canvas painting through techniques such as slashing, pouring, dripping, and so on.

White Painting reveals textural layers of oil paint and a broken black line that creates a violent rupture in the composition. Through dynamic markings and subdued colors, this work captures the collective’s interests in materiality, movement, and the human spirit.

Through his paintings, Mark Rothko aimed to transcend everyday experience and immerse the viewer in contemplative space. While his paintings follow a fixed format—consisting of two or three soft-edged rectangles or squares floating against a field of color—the result was never predictable.

Through this play of color and space, Rothko sought an emotional and spiritual exchange with the viewer.

“I am interested only in expressing the basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on,” Rothko explained. “The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.”