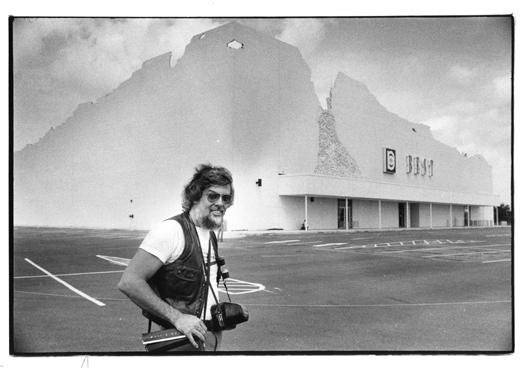

James Wines, founder and president of SITE (Sculpture in the Environment), a New York City–based architecture and environmental arts organization, visited Carnegie Museum of Art in late June to give a lecture titled “A Line Around an Idea—Drawing in a Computer Age” and host a public workshop. During his lecture, Wines discussed the history of calligraphic content in art and architecture as a means of clarifying the inseparable connections between mind and hand for the development of conceptual ideas. It’s a topic Wines is particularly passionate about, as drawing has always been central to his art practice.

An architect, sculptor, and writer, Wines has remained a prolific force throughout his distinguished career. From inverting expectations of what a “big-box” store should look like via BEST Products Company, to envisioning the Museum of Islamic Arts in Doha, Qatar, as a landscape of rolling sand, Wines has over four decades of successful practice, and often stresses that in this age of computer rendering, drawing by hand remains vitally important in the fields of architecture and design.

As curator of the exhibition Sketch to Structure, spotlighting the visionary work that James Wines produced through SITE made perfect sense. Not only from a thematic perspective, but because of Wines’s dedication to architectural design as an experimental process that fosters new and innovative ideas. In advance of his visit, I asked Mr. Wines a series of questions about his approach to art and architecture, with a particular focus on the atypical big-box showroom designs he created for BEST Products Company in the 1970s and 1980s.

Alyssum Skjeie: Your designs for BEST were creative, intriguing, sometimes confusing to shoppers, and were a new way of thinking about suburban “big-box” stores in the 1970s. Can you explain some of your inspirations for BEST, and why it was important to rethink the “big-box” store?

James Wines: First, I need to include a little background before discussing the BEST buildings. In the early 1960s I was a Constructivist-influenced sculptor, producing public art for corporate and civic clients. By the late 1960s, I started questioning the motivations behind ‘object thinking’ and the proliferation of isolated sculptures sitting in parks and plazas. I became increasingly aware that the exclusive language of private art was not interchangeable with the inclusive language necessary for public art. I also realized that the failure of artists to take these differences into account had left American cityscapes pock marked with endless facsimiles of private art—too large for containment in an art gallery or museum and too insular for communication in the public domain.

My views were shared by a number of colleagues in the art world; so, by 1965, there was a robust incentive among a group of artists in New York to reject the confinement of gallery exhibition spaces and move outside with interventions that excluded the conventional art showcases. A rebel group of artists, living in the SoHo District—Gordon Matta-Clark, Alice Aycock, Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt, Mary Miss, Michael Heizer, and others—ventured into the streets and landscape. As a participant in the emerging environmental movement and disenchanted with the whole public art scene, I wrote a critical essay for Art in America titled “Public Art–Private Art” in January 1970. The essay introduced two terms—“plop art” and “turd in the plaza”—as disdainful descriptions of interior objects masquerading as public works.

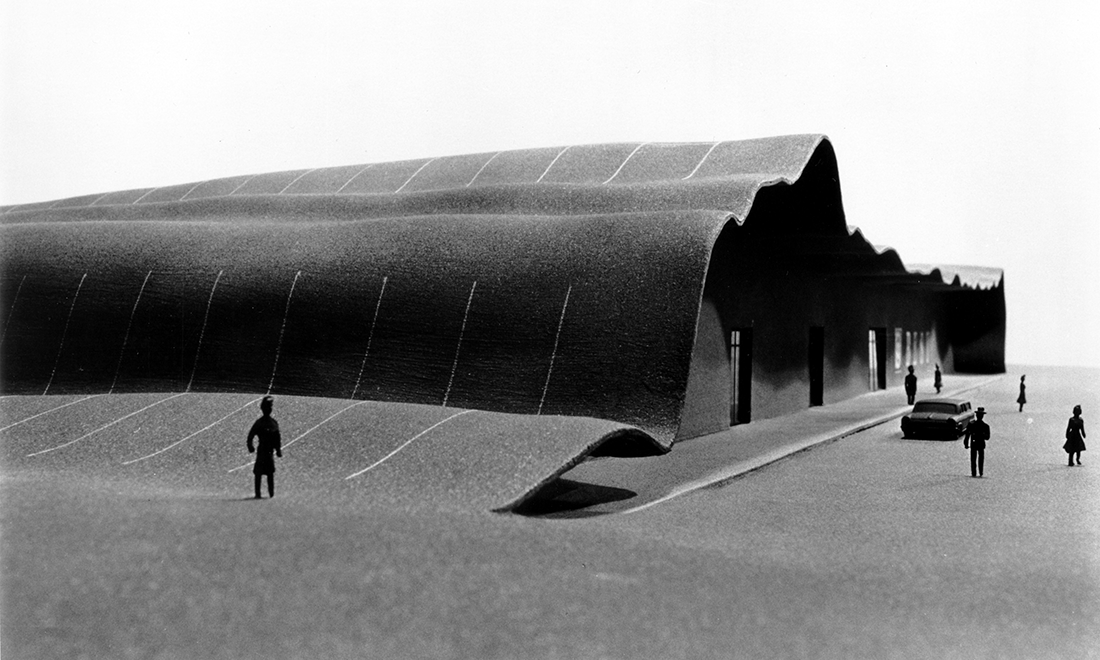

I had sold a few early sculptures to art collectors Sydney and Frances Lewis, so when they asked me if I would be interested in creating some art for BEST Products Company’s big-box stores, I responded enthusiastically. My first step was to discourage them from using any kind of sculpture as a form of décor on their buildings. The timing for this commission was ideal. I had always been interested in the connections between art and architecture, but here was a situation where the subject matter of art could be architecture itself.

In defense of his collage works Picasso astutely observed, and I’m paraphrasing here, that “You can’t create art out of the Parthenon. Instead, you make art out of the debris under your feet.” Like discard materials, the banality of the big-box store was a totally untapped and fertile territory for transformation—offering an opportunity to place art where people would least expect to find it. As an image of reflex identification, the American public subliminally accepted the shopping center prototype as an intrinsic (and unseen) presence in daily life. I also realized that, out of contempt for the ubiquity of big-box stores, no self-respecting Harvard architectural graduate would touch this lowly level of design with a ten-foot pole. But it was a perfect challenge for the nascent SITE studio—offering an ideal context for the inclusion of social, psychological, cultural, structural, and environmental commentary, as well as the use of architecture as a critique of architecture.

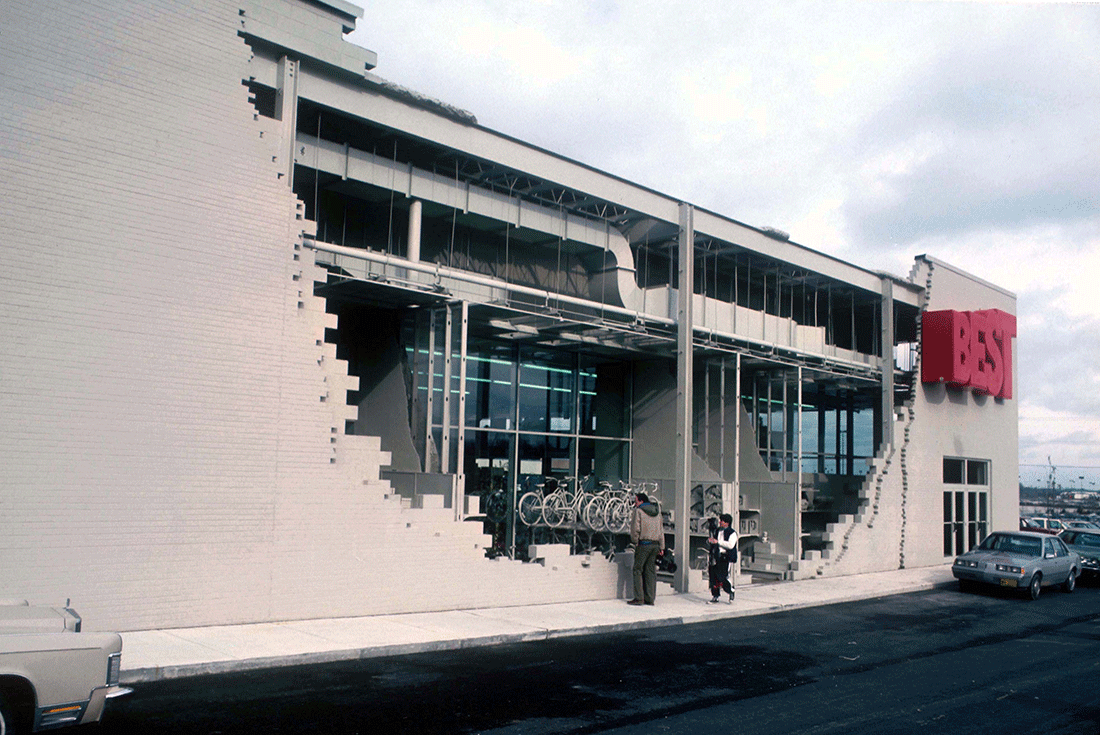

As confirmation of the BEST building’s success—and heartening evidence of its conceptual distance from the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s formalist baggage—a local Texas cowboy attending the opening of the Houston Indeterminate Façade remarked: “You know, that’s what I’ve always wanted to do…kick the shit out of one of those big-box stores.”

Alyssum Skjeie: The architecture varies greatly for the BEST stores you designed—from a peeling wall to a movable corner that created the entrance, to façades with living plants. Did location play a key role in your thinking and creative process for BEST?

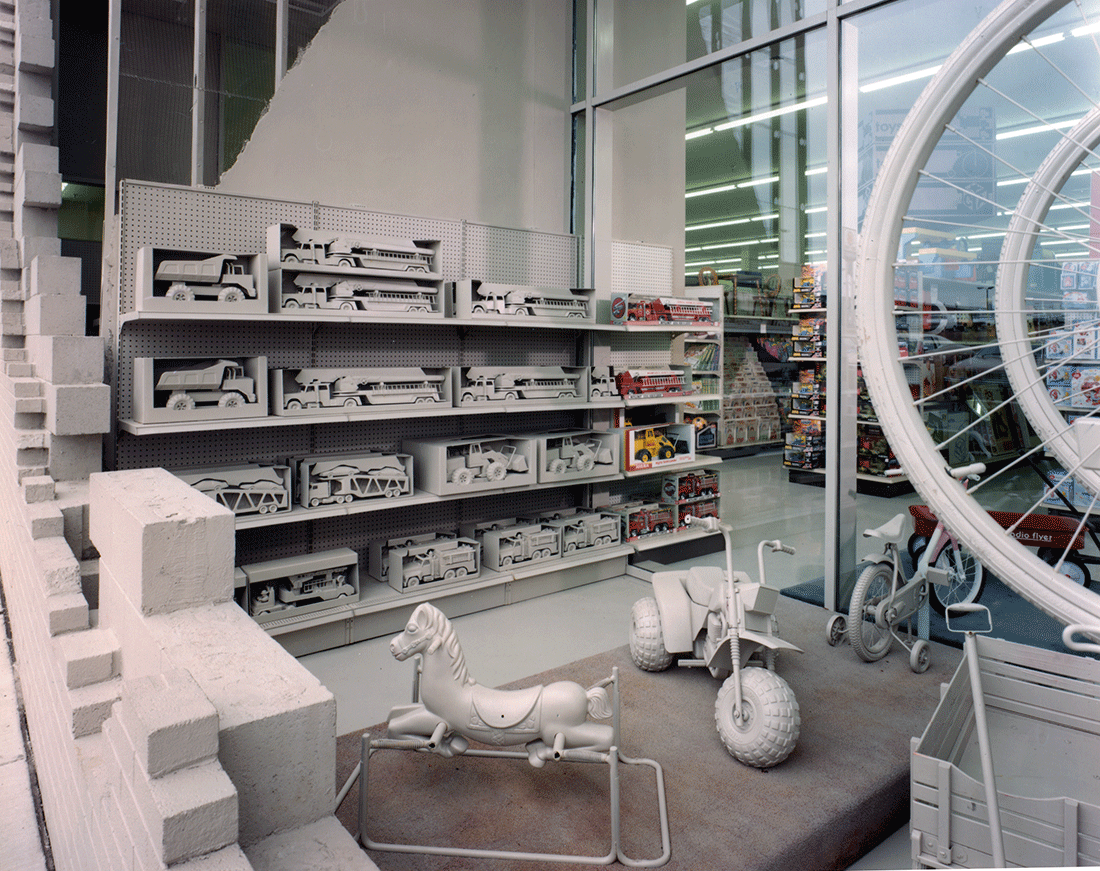

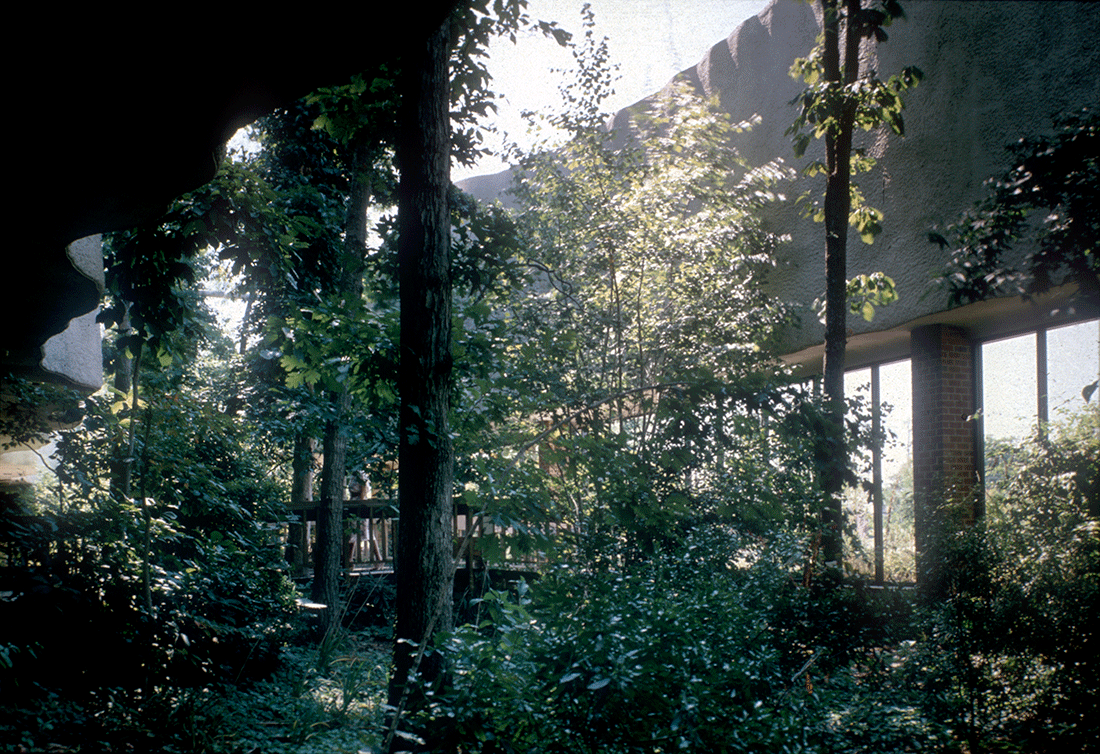

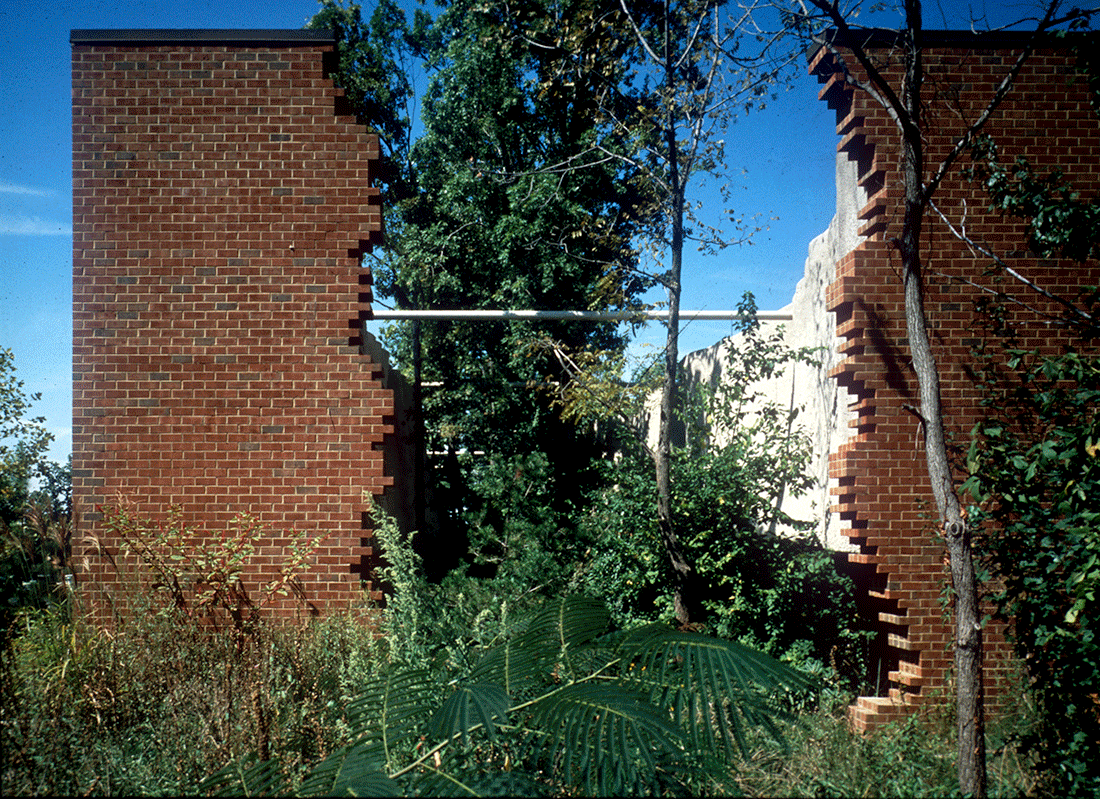

James Wines: All of SITE’s work from the beginning has been based on contextual response. Sometimes this acknowledgement of surroundings has taken the form of critical commentary on cultural values (as in most of the BEST buildings). Other times this integrative process has included references to existing physical features, like landscape, topography, geology, and surrounding neighborhoods. In all of our studio’s work there has been a consistent intention to view architecture as an art of idea, attitude, and context, as opposed to being interpreted exclusively as the product of design with form, space, and structure. For example, in the case of the BEST Houston Indeterminate Façade and Milwaukee Inside/Outside stores, these structures were based on architectural critique and an inversion of expectation, where the processes of building and un-building became part of the final concept. In the Richmond Forest and Miami Rainforest buildings there was a concerted intention to include existing landscape as an intrinsic element in the fusion of architecture with the natural environment.

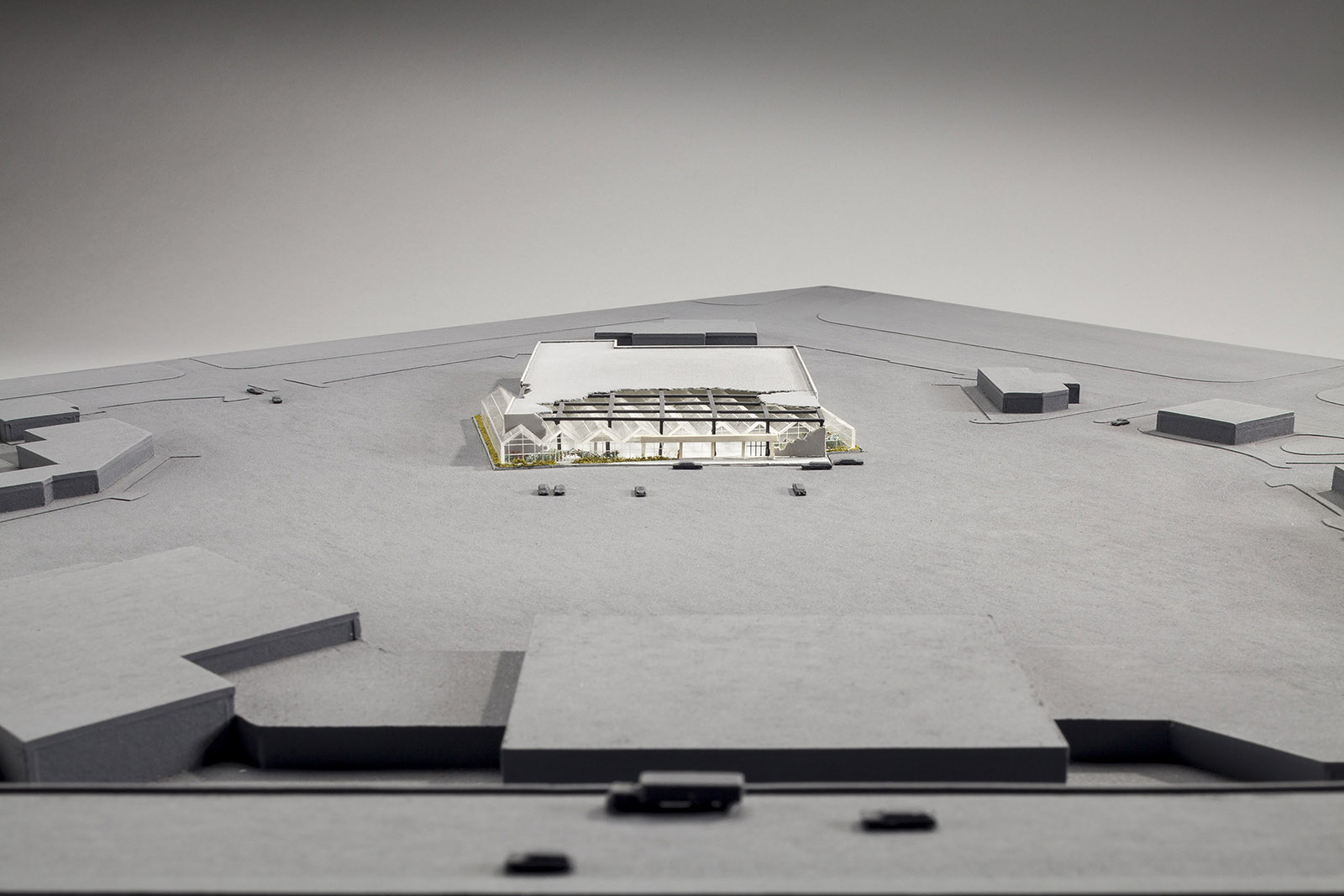

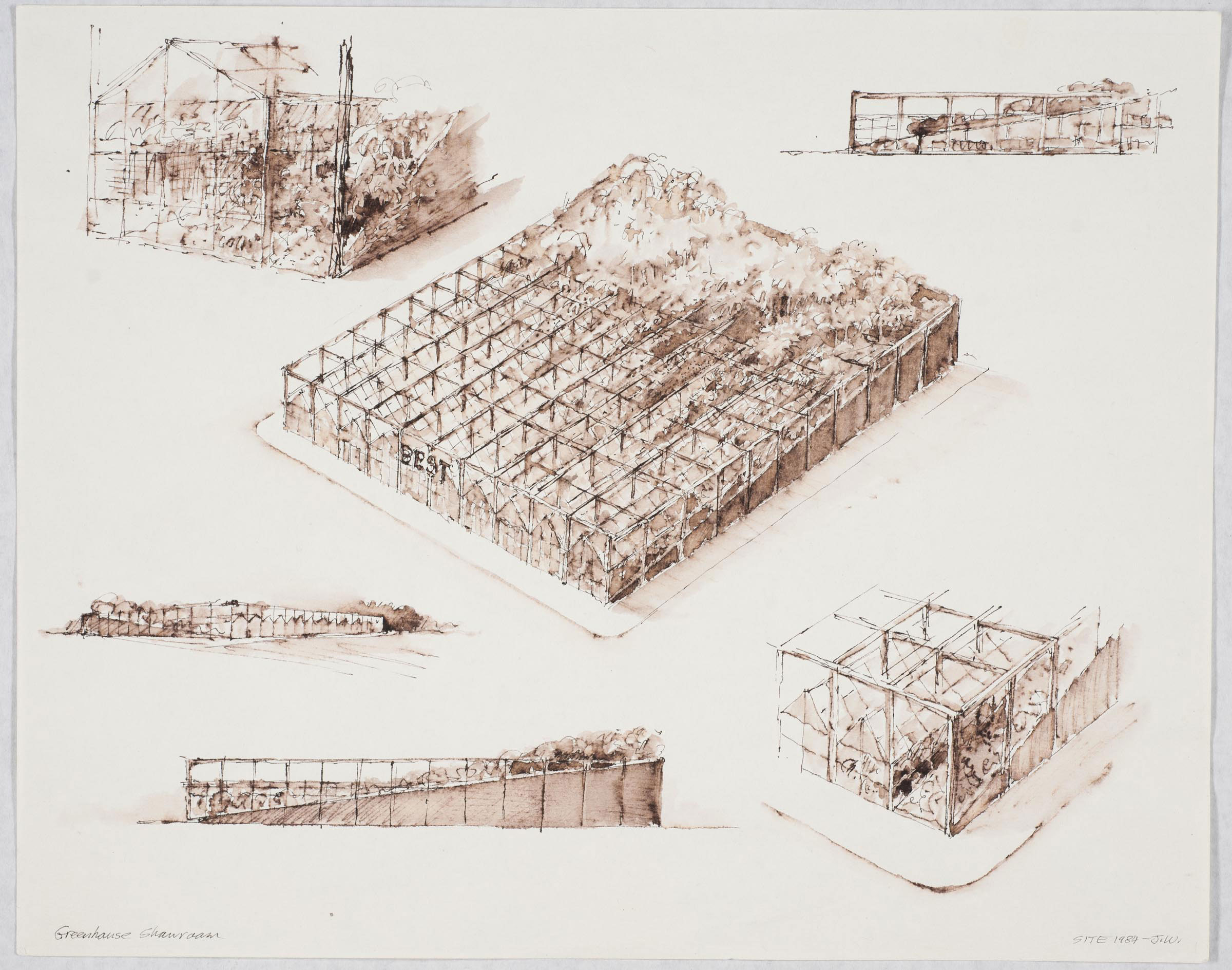

Alyssum Skjeie: Last year, the Heinz Architectural Center here at Carnegie Museum of Art acquired four drawings and one model for a proposed BEST showroom for San Leandro, California. Can you talk about your creative process for this specific proposal? The sketches seem to show you thinking and rethinking a greenhouse, through dozens of small perspective, plan, and elevation drawings. Why is it important to sketch an idea various times?

James Wines: First of all, I want to compliment the curatorial leadership of the Heinz Architectural Center for its progressive policy in crediting the creative process, as opposed to only collecting individual drawings as aesthetic objects. In my view, this acknowledgement of design evolution is the most intelligent and educationally productive way to exhibit architecture—especially when the actual built edifice is usually far away and neither photos, nor individual renderings, can adequately tell the story. By illuminating the process, the general public and scholars are able to witness an entire range of contextual references and selective aesthetic strategies, plus experience trial-and-error sketches that search for design solutions. The BEST Greenhouse Showroom in San Leandro is a demonstrative example of graphic art development. The challenge, in this case, was to integrate a collection of Japanese-owned greenhouses—which the local community wanted to preserve—as part of a new big-box center. This juxtaposition of flower and vegetable farming with a BEST store was an intriguing inversion of situation from the outset; so the many variations described in sketches were generated to explore a wide range of potential resolutions. Unfortunately, California code restrictions prohibiting the enclosure of farming and hard goods merchandizing under one roof defeated the whole endeavor; so the project wasn’t built.

Given my preference for hand drawing, I agree with Picasso’s assessment of his own proclivities; “I draw like other people bite their nails.” I have sketched for my entire life and consider this investigative means as essential for uncovering and explaining thought process. Also, there are incredibly fertile graphic elements I call “subliminal accidents.” They are the unconscious scribbles that flow from a pen or brush—often without any particular objective—which can generate rich calligraphic content and a kind of magical catalogue of thoughts that aren’t immediately tangible. I have often observed that, when drawings are executed with too much control and rational sense of purpose, this elusive source of ideas can be lost.

Alyssum Skjeie: BEST Products went out of business, and many of the stores you designed have been drastically changed. How do you see the evolution of the “big-box” store? Was BEST an exception to often monotonous suburban design?

James Wines: The fate of all BEST stores—with the exception of the Forest Building in Richmond—is simply the consequence of rapacious commercial development in the USA. The lifespan expectation of almost any shopping center is about fifteen years, even in the most favorable of circumstances. While the ten BEST stores were conceived as art works—which, in a museum context, would assure respect and preservation—any building left to the mercy of American merchandising is doomed from the outset. The systematic elimination of the BEST stores in the name of “progress” has been difficult to experience; but, as the architect, my only choice is to remain philosophical and succumb to the system. When most of the BEST buildings were destroyed in the 1990s, an article appeared in an architectural review in France, condemning commercial America’s barbaric actions and claiming that, if such art works were in France, they would attain the status of national monuments. Although these sentiments helped reinforce my ego, I am not sure that French developers would have been any more respectful of art on the highway than their American counterparts in a greed-driven and/or volatile economic environment.

The situation with the Richmond Forest building is an anomaly. When I heard in the 1990s that this store had been purchased for conversion to a Presbyterian church, I was elated by the prospect of civic/religious appreciation and the assurance of preservation. The reality, over a five-year period, became one of such blatant destruction that I kept hoping the structure would be mercifully removed in its entirety. At great financial investment—and for no apparent functional advantage—the entire breadth of aesthetic quality was erased. The local architect in charge removed major trees and ground cover, built concrete sidewalks through the landscape spaces, eliminated the façade terrarium gardens and, in the end, managed to cancel out all conceptual/environmental intentions of the original integration of a natural forest with architecture (see here). My only explanation is that this particular church administration embodied a profound—and I assume, ecclesiastically motivated—distaste for both nature and architecture.

Alyssum Skjeie is program manager for the Heinz Architectural Center at Carnegie Museum of Art. Her role includes collaborating on all exhibitions and HAC Labs, managing the architecture collection, which includes over 6,000 objects from models, to drawings, to photographs, and collaboratively programming various events and lectures for the Heinz Architectural Center. She has assisted on nearly a dozen exhibitions in the Heinz Architectural Center galleries, and is the curator of Sketch to Structure, an exhibition that explores the architectural design process. Alyssum holds a master’s in architectural history from the University of Virginia, and is passionate about explaining architecture and urbanism to visitors through innovative and purposeful exhibitions and programs.

In 2014, the Heinz Architectural Center at Carnegie Museum of Art acquired a suite of drawings and one architectural model for a proposed BEST Products store in San Leandro, California. The exhibition Sketch to Structure—which features a short documentary, architectural drawings, and model from SITE—is on view in the Heinz Architectural Center at Carnegie Museum of Art until August 17, 2015.

The exhibition Sketch to Structure—which features a short documentary, architectural drawings, and model from SITE—was on view in the Heinz Architectural Center at Carnegie Museum of Art until August 17, 2015.

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.