It’s a cold morning in early December and cartoonist Frank Santoro is sitting in the kitchen of his Swissvale row house, WKCR-FM tuned in on a nearby radio as he sips coffee from a white ceramic mug. The sounds of Sun Ra swell in the background as dull sunlight glimmers through a window above the kitchen sink. Heat from a radiator warms the room as Santoro, whose brown cardigan partially obscures a Kennywood Park T-shirt, talks Pittsburgh and the city’s influx of new blood.

“It’s such a strange feeling to see all these carpetbaggers [coming to town],” he says, laughing a bit. Santoro is referring to the legions of outsiders who have flocked to Pittsburgh in recent years, many fleeing places like Portland, Los Angeles, and Chicago in search of cheap rent and a new scene. After leaving home and living elsewhere for 20 years, he doesn’t necessarily begrudge the city’s newcomers. He’s well aware of the city’s allure. If anything, the desire to live in an affordable place is something he intimately understands.

“I moved back to Pittsburgh because I saw friends burn through $80,000 a year,” Santoro says, referring to the high cost of living he experienced during long stints in some of the country’s priciest cities. Most notably San Francisco, where Santoro relocated after dropping out of art school. And later New York City, where he spent five years working as an assistant to Italian painter Francesco Clemente.

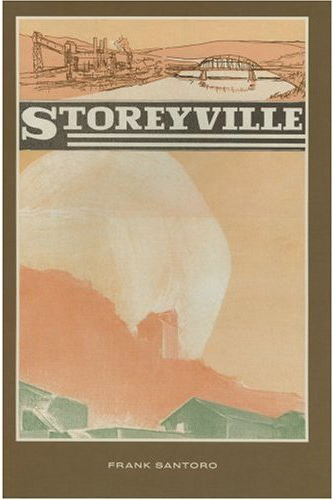

It was during his time away, however, that Santoro cemented his reputation as an innovator in the world of underground, art-minded comics. First by publishing his Sirk zines in the early 1990s, but more substantially with the 1995 release of Storeyville, a 40-page graphic novel that tells the tale of a young hobo’s journey to track down his missing mentor. The book quickly attained cult status, and today is still cited by many comic creators, including Chris Ware, as a major influence.

So when Santoro returned to Pittsburgh in March 2007, he had a distinct vision for how he wanted to continue making comics.

“I [used to visit] Gary Panter a lot in his Brooklyn house/studio in a remote part of [the borough],” Santoro explains, adding that he liked how the area felt nothing like New York. “So I said, ‘That’s what I want.’” Upon his return to Pittsburgh, Santoro learned that his mother was preparing to rent his grandparent’s house, so he seized the opportunity and purchased the home from his family. At the time he also began work on Cold Heat, a collaboration with cartoonist Ben Jones, and a marked departure from the subject matter covered in Storeyville.

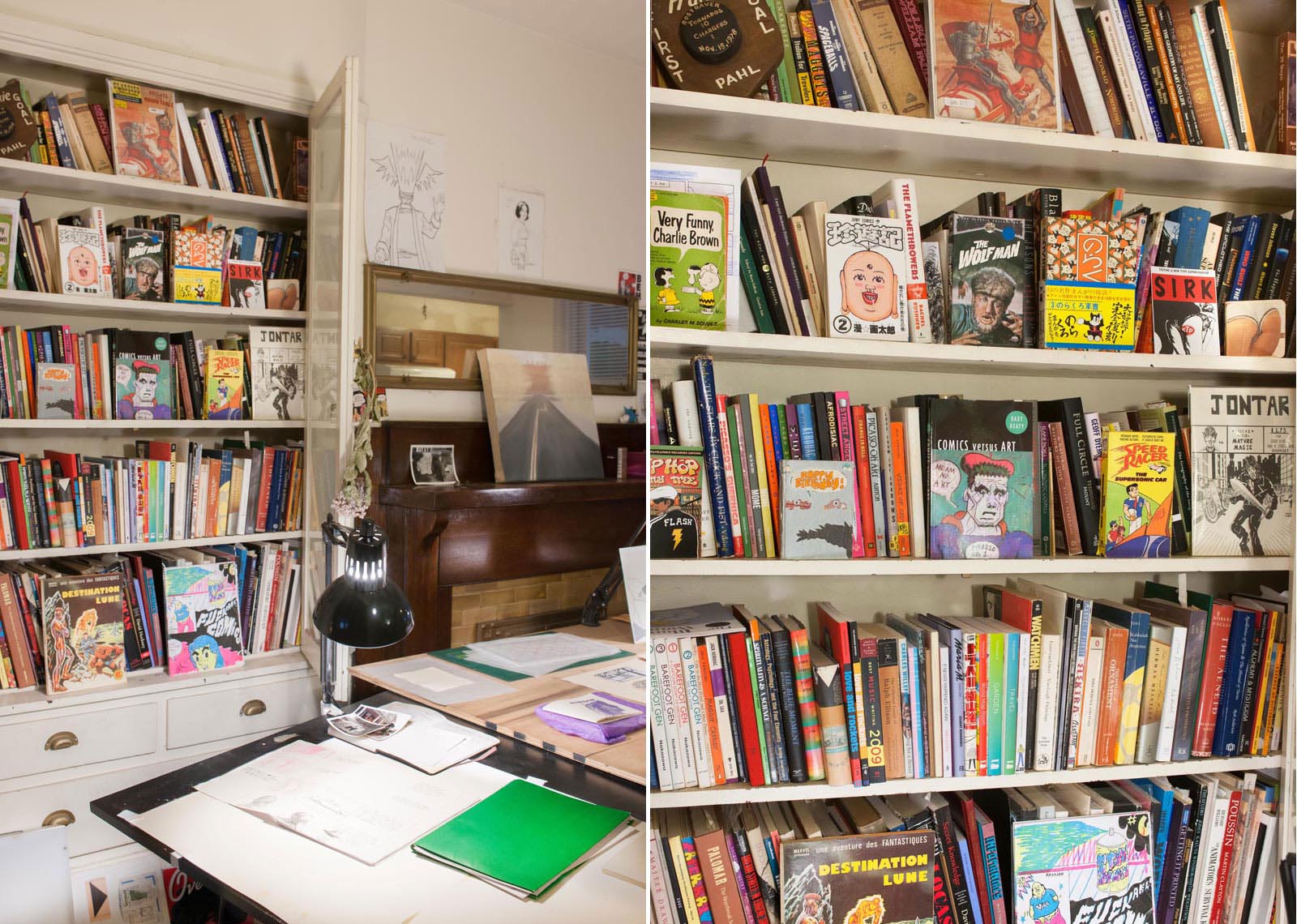

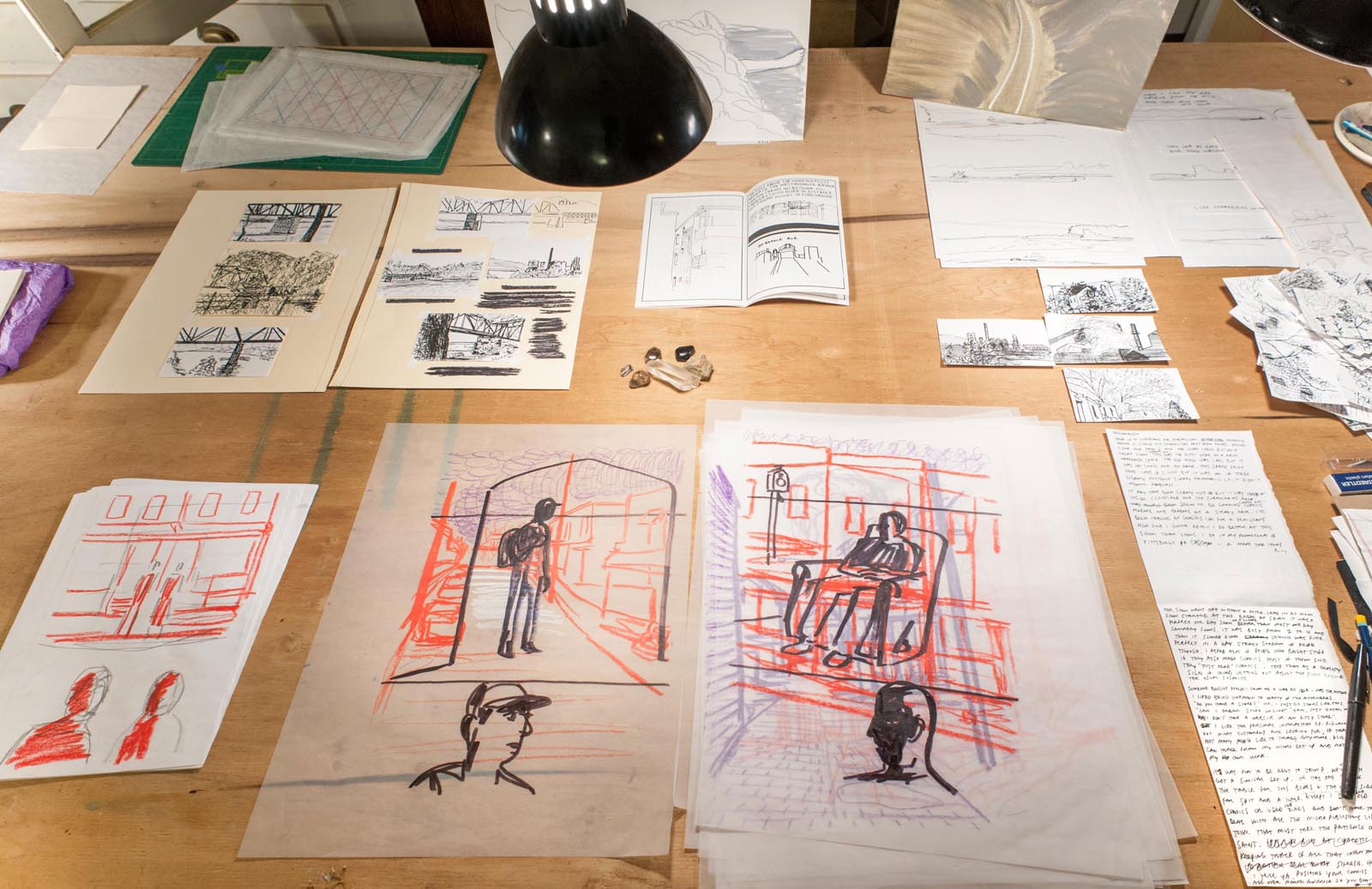

Today, as you enter the Swissvale row house where Santoro has centered his art practice for the last eight years, there’s almost a tangible sense of calm. To say that Santoro is relaxed would be misleading; Zen-like is more apt. And his disposition is reflected in the house. The rooms are dimly lit but inviting, lamps placed like beacons throughout the first floor—illuminating a chair and end table in the living room, his sprawling work surface in the dining room. Jazz instrumentals fill the air, as does the aroma of coffee. Sequential black-and-white sketches sit in a pile at one end of his desk, while stacks of comic book boxes populate the space beneath. Above his drafting table, built-in cabinets hold books by Alan Moore, Rachel Kushner, John Haskell, Paper Rad, Jack Kerouac, and Charles M. Schulz, to name only a few. It’s a space brimming with history yet firmly rooted in the present.

Situated on a dead-end street across from the former Union Switch & Signal building, now home to a strip mall, Santoro’s row house is hidden in the relative obscurity of Swissvale. With its squat and sturdy architecture, it’s a design ubiquitous throughout the city’s postindustrial expanse—from Swissvale to Wilkinsburg, Homewood to Lawrenceville. As de facto housing for generations of the city’s mill workers and laborers, the silhouette of a row house is easily just as iconic as Pittsburgh’s Point State Park or the Duquesne Incline. So perhaps it’s only fitting that Santoro, an artist so deeply informed by home and a sense of place, works out of a row house in the neighborhood where he was raised.

“Swissvale [represents] this weird inter-zone in the city,” Santoro says, citing how the neighborhood is trisected by Squirrel Hill, Edgewood, and Rankin, yet seemingly a world of its own. In many ways, much like Panter’s corner of Brooklyn. As Santoro talks about the place where he grew up, where his school years were spent head down in a sketchbook, his affection for the neighborhood is evident—not only in the tone of his voice, but in the intensity of his blue-eyed gaze. After all, his familial ties to Swissvale, and Pittsburgh in general, are lovingly reflected in much of his work. In fact, stand outside Santoro’s row house and it’s almost impossible not to experience déjà vu if you’ve ever read any of his comics.

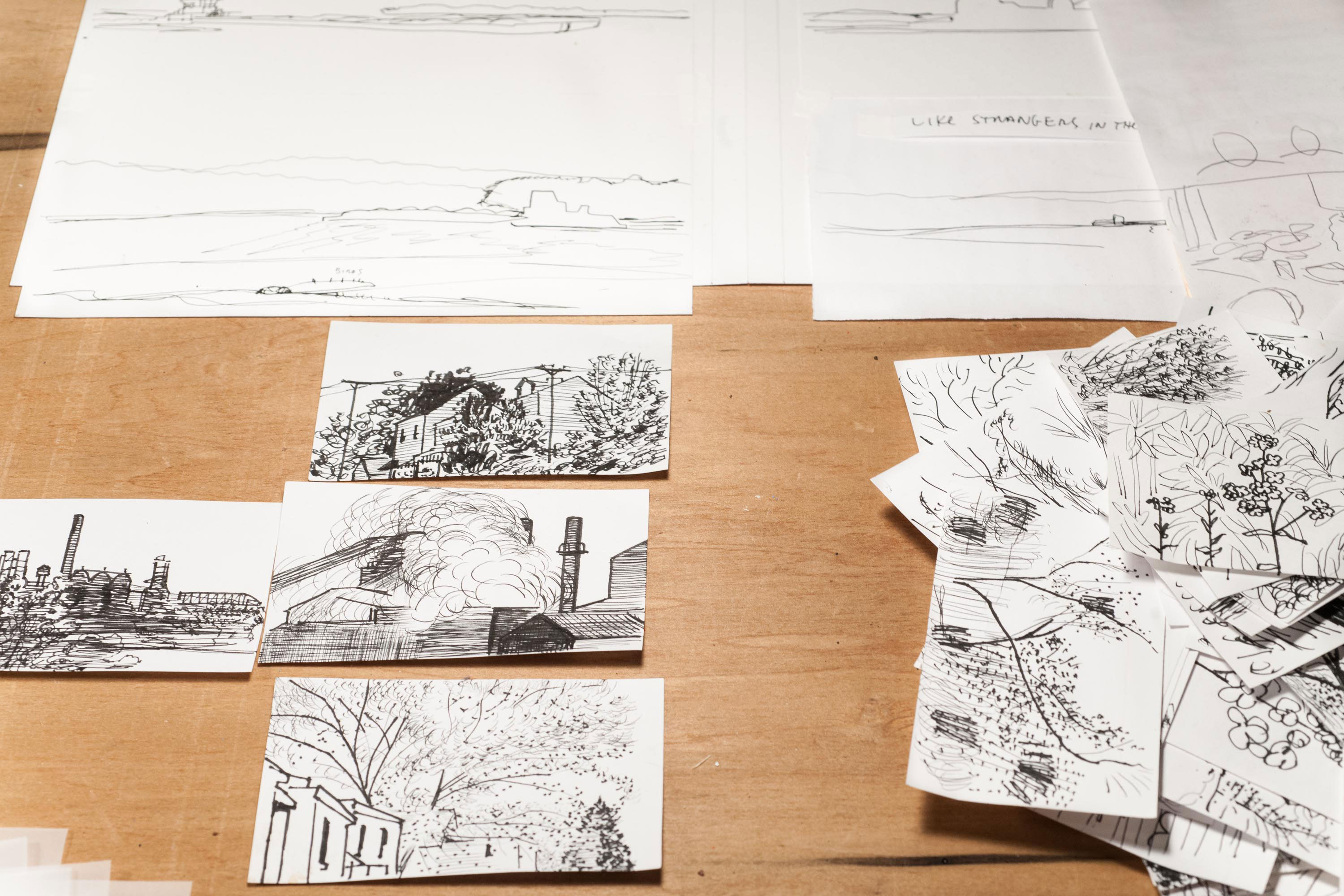

A perfect example is Blast Furnace Funnies, Santoro’s newsprint comic published as part of the 2011 Pittsburgh Biennial. A bittersweet love letter to Pittsburgh, and Swissvale in particular, the hand-drawn landscapes, row houses, and steel mills in each panel are dreamlike, as if the entire comic was extracted from the utopic mists of childhood memory. A powerful companion to the exquisite illustrations, Santoro’s writing infuses the comic’s vivid colors with a lyrical narrative. To give an example, the comic offers a poignant recurring passage, “This city is like Pompeii to me,” that Santoro invokes to describe Pittsburgh. It’s a phrase that appears in several iterations: “This city is like Pompeii to me, a ruin that used to be.” “This city is like Pompeii to me, a glory that was and will always be.” These poetic exercises in repetition allow Santoro’s rich, heartfelt narrative to deepen as you move panel-by-panel through the comic. They also succeed in telling a story where the place is as much a character as its people.

“The little postage stamp of land where you are from is the most valuable thing to you as an author,” Santoro says, paraphrasing the advice that Sherwood Anderson once gave to William Faulkner. It’s his quick answer, he says, for why Pittsburgh acts as a prism for his narratives. If you consider that quote for a moment, Santoro’s creative approach becomes even clearer. Not only do his comics pay homage to a city and its people, but offer a visual record of a particular moment in time. It’s an idea that poet Adrienne Rich once beautifully encapsulated with the line: “A place on a map is also a place in history.” For Santoro, Pittsburgh is both a physical and spiritual place in that continuum.

“The little postage stamp of land where you are from is the most valuable thing to you as an author,” Santoro says, paraphrasing the advice that Sherwood Anderson once gave to William Faulkner.

“I’ve traveled all over the States,” he says. “Crossed the country over ten times by car and have lived on both coasts and in the Southwest, and I gotta say, there is something very special about Pittsburgh beyond my own nostalgia. I only realized this year that the Homestead Strike took place just across the river from the Swissvale side of the Monongahela. It’s wild to me to feel so connected to American history here in Pittsburgh. We figure into so much of it and didn’t die like Detroit. So there’s something there—narrative gold—that I want to mine out of myself.”

His left arm resting on the emerald-green table in his kitchen, Santoro leans against a wall dotted with sketches, paintings, and comic panels—some his own, others from friends and comics creators he admires.

“I want to be an artist of my time,” he says, “and I think comics is like film in the early part of the last century. Storytelling is so different than anything else. It’s not about sitting down and painting a Cézanne or trying to re-invent the wheel. I like to say that you can paint the Mona Lisa but if it hangs in the garage, who’s gonna know? Communication is built into the DNA of comics. It’s about telling stories. So it’s a weird alchemy.”

Mastering that alchemy is the trick. Santoro’s approach, which favors expressive illustration anchored by a powerful narrative, has often produced the right combination.

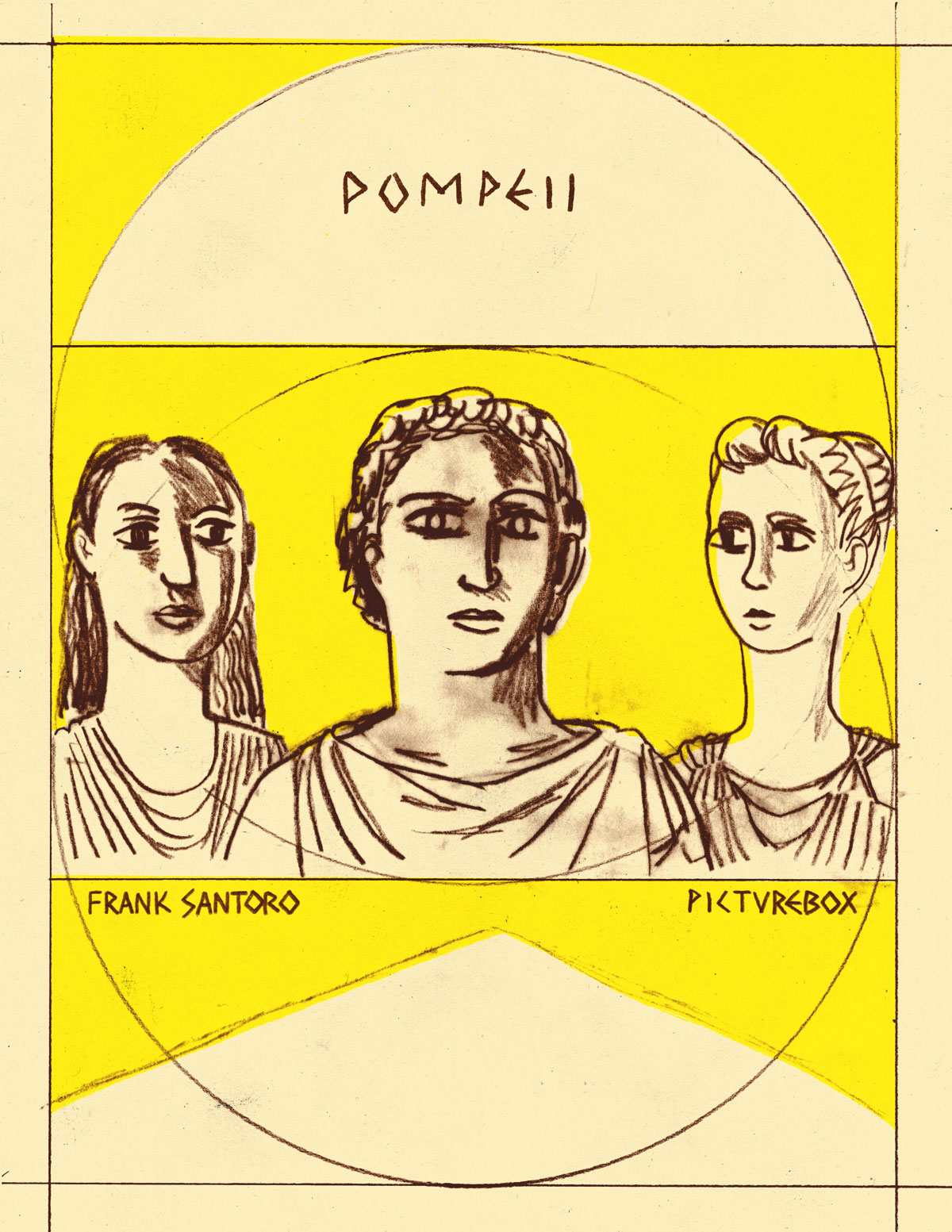

“Santoro is a consummate storyteller, one whose work is as much about flesh as form,” Adam McGovern wrote in his 2013 review of Pompeii for the Los Angeles Review of Books. The graphic novel, published by PictureBox, is Santoro’s most recent work. In Pompeii, he examines the relationship between a painter and his assistant in the days before the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The illustrative style of the book, which employs spare monochromatic sketches, is as much an exercise in storytelling as it is a meditation on craft.

The thoughtful originality of Santoro’s ideas have served him well in his career—if not always financially, at least critically. His books are well-received and have a built-in audience of smart, culturally savvy readers. But making money in underground comics, let alone a living, remains a challenge.

“There’s no financial support in comics,” Santoro says. “I’ve never sold enough of my own books to support myself.” Yet still, through comics, Santoro ekes out a living. Just not in the traditional sense of being paid well to solely produce his own books. Continuing a cartooning tradition started by Charles N. Landon in Cleveland, Santoro augments his publishing income through his popular correspondence course, where he teaches students from all over the world how to make comics (his annual Summer School session started earlier this month). He then offers those students a forum for their work through his Comics Workbook site. Another source of income for Santoro is his role as a bookseller.

“A big part of my art practice is being a collector of old rare comics,” he says. “Not necessarily valuable comics, but collecting comics that succeed in transmitting a powerful story through that weird alchemy [that I mentioned earlier]. Most of these comics aren’t part of the traditional canon. So I collect these books, I write about them [for The Comics Journal], I sell them, I share them online and in doing so contribute to a larger oral tradition, I think, that creates a practice and hopefully some sort of community.”

The notion of community is important to Santoro, which is not only reflected in his dedication to teaching, but in his connection to the comics scene here in Pittsburgh. Though it’s a small, tight-knit community, the scene in the city has steadily grown over the years, with artists like Ed Piskor, Jim Rugg, Jason Lex, and Daniel McCloskey, to name only a few, producing work that is engaging yet wildly different in individual style. To nurture this community, Santoro, with help from friends, started the Pittsburgh Comics Salon, which meets each month at Lili Café in Polish Hill and encourages conversation about the art and business of comics. The salon is also hosted in the same building as The Copacetic Comics Company, a local resource for underground comics, zines, and art-minded books. Santoro, a regular at Copacetic, is quick to heap praise on the shop’s proprietor, Bill Boichel.

“I learned everything from Bill,” he says. “[I consider him] my mentor.” Santoro adds that his first foray into comics was actually at the age of 16, when Boichel, who was then publishing zines and comics in the basement of his BEM comic shop in Wilkinsburg, included Santoro’s work in one of his BEM Publications. Santoro’s exposure to self-publishing, as well as the independent and avant-garde comics that Boichel sold at BEM throughout the 1980s and 1990s, was extremely influential—both as an artist and collector. And those early experiences have helped guide him through his career and inform his views.

“Being a great illustrator does not necessarily make you a great comics maker,” Santoro says. “I’m a writer and an artist. Saying I’m an artist sounds too pretentious, I think. And then if I say I’m a cartoonist, people think I draw Garfield the cat.”

Matthew Newton is director of publishing at The Andy Warhol Museum, where he oversees all editorial, design, photographic, and digital content for the museum, including exhibitions, books, and special projects. Prior to joining The Warhol, he was director of publishing at Carnegie Museum of Art, where he also founded Storyboard, the institution’s award-winning online arts journal. He has written essays, many about class and culture, for Guernica, The Oxford American, and The Rumpus, and his reporting has appeared in The Atlantic’s CityLab, Esquire, Forbes, and Spin. He has been awarded grants and fellowships from Creative Capital, Staunton Farm Foundation, Creative Nonfiction, Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council, and Pittsburgh Center for the Arts. His debut nonfiction book, Shopping Mall, was published by Bloomsbury in September 2017.

This essay was a finalist for a 2016 Golden Quill Award recognizing excellence in regional journalism.

Storyboard was the award-winning online journal and forum for critical thinking and provocative conversations at Carnegie Museum of Art. From 2014 to 2021, Storyboard published articles, photo essays, interviews, and more, that spoke to a local, national, and international arts readership.